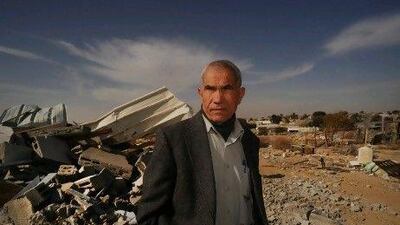

One man’s futile quest to prove ownership of land in the Al Araqib area of the Negev desert shows how Israeli law is weighted against the Bedouin as the cabinet approves a plan to move 30,000 clan members into urban townships.

HURA, ISRAEL // Nuri Al Okbi’s home is an archive of his futile campaign to prove to Israel that he owns land he says has been in his family for centuries.

Tucked away in boxes and stacked on bookshelves are maps and land deeds dating back to the Ottoman Empire.

The collection, he says, is evidence of the Okbi clan’s ownership of land in the Al Araqib area of Israel’s Negev desert.

Shortly after its founding in 1948, Israel seized huge swathes of Bedouin land in the Negev, including Al Araqib. Thousands of Bedouin, such as the Okbis, were expelled or confined to urban slums. They became squatters on their ancestral land.

Mr Al Okbi, 69, says he has spent decades trying to convince Israeli courts that he owns a piece of the Al Araqib land.

So when he heard last year of Israel’s plan to uproot thousands of its Bedouin citizens from an area called Sigagh, Mr Al Okbi’s suspicions were confirmed. Israel, he concluded, would never recognise his people’s nomadic way of life and historic ties to the land.

“We have tried the law for so long to get our rights but there is no law in Israel – at least not for the Bedouin,” he says.

The plan, approved by the Israeli cabinet in September, calls for relocating more than 30,000 Bedouin from the Sigagh villages that Israel considers illegal, to townships built by the government.

The recommendations were made by an Israeli committee formed in 2009 and were included in the Prawer Plan, named after the committee’s chairman, Ehud Prawer.

Moving the Bedouin is one of many recommendations that would give Israel control over much of the land in the Sigagh and, ostensibly, ease the poverty and marginalisation facing the Negev Bedouin. The Knesset, or parliament, is expected to vote on the plan soon.

To critics, the Prawer Plan is little more than a government land grab. They see it as an attempt to further confine Bedouin to slums while seizing more land to build Jewish communities.

“It’s a declaration of war on the Bedouin,” says Thabet Abu Ras, director of the Negev office of the Legal Centre for Arab Minority Rights.

In a report released in April, the Association for Civil Rights in Israel used phrases such as “grossly violate” and “enshrine wholesale discrimination” to describe the Prawer Plan’s effect on Bedouin.

These organisations fear its implementation could shatter what were once cordial relations between the Israeli government and its Bedouin citizens, some of whom serve in the military.

The plan tries to tackle the issue of the Sigagh’s three dozen unrecognised villages. Home to about 70,000 Bedouin, these shanty towns are not recognised by Israel, even though some existed before the nation’s creation.

Because Israel considers them illegal, the villages lack municipal water supplies, electricity and other basic services. Israeli authorities regularly demolish homes because they were built without permits.

About half of the village residents would be moved to unspecified locations under the plan, which proposes a compensation scheme to settle Bedouin claims to some 60,000 hectares in the Negev.

Mark Regev, a spokesman for the Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, will not give details on which villages would be affected or where their residents would be relocated. The government, he says, is in the “process of dialogue with the Bedouin community in the Negev”.

But Bedouin leaders say the government has refused to consult them and they fear residents will be moved to the seven crowded and troubled townships in Sigagh.

About half of the 190,000 Negev Bedouin have moved into the townships – some of Israel’s poorest, most crime-ridden communities – which are to receive about US$320 million (Dh1.17 billion) of improvements under the Prawer Plan.

Israel could then build more Jewish communities in the vacated villages – the reason community leaders suspect the government has refused to legalise the villages.

“I’m doing everything I can to stop a violent confrontation but I can’t promise anything anymore,” says Ibrahim Abu Afesh, 58, an elder of Wadi Naam, one of the unrecognised villages.

“Give me a proposal that I can work with and I’d be willing to talk. But we’ve been told nothing.”

The Bedouin comprise less than a third of the Negev’s population but Jewish-Israeli leaders fear their high birth rates. According to government statistics, the Bedouin population doubles every 15 years and is projected to reach 300,000 by 2020.

In 2000, the former Israeli prime minister, Ariel Sharon, described the Negev Bedouin as “gnawing away at the country’s land reserves, and no one is doing anything significant about it”.

Itay Epshtain, co-director of the Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions, says Israel wants more Jewish residents in the Negev. But few are interested.

Although the Negev makes up 60 per cent of Israel’s land, only about 500,000 of Israel’s 5.5 million Jews live there.

So in the late 1990s, the government began allocating large tracts of farmland – more than 8,100 hectares – to individual Jewish families.

“Israel isn’t talking about urbanising Jews here. It’s the opposite – they are encouraged to build farms,” Mr Epshtain says.

Mr Okbi expresses doubt that Israel will offer the Bedouin a fair solution, let alone his claims to 120 hectares in Al Araqib.

Precedent has made him a pessimist. He shows documents he says hold promises made by Israel’s military to return his family to their ancestral land in Al Araqib shortly after their eviction in November 1951.

“That was over 60 years ago,” Mr Okbi says. “The problem with Zionism is, it will run over anyone who’s not a Jew, even if you’re Israeli.”

Follow

The National

on

& Hugh Naylor on