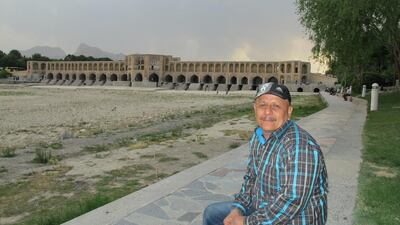

Isfahan, Iran // A bitter smile appeared on Hamid Khorshidi’s face as he sat next to the bone-dry Zayandehrood River, remembering when water flowed between its banks in this central Iranian city.

“It meant everything to Isfahanis, but it is just a name now.”

The Zayandehrood, which means “life-giving river”, is the largest river in central Iran and a major source of water for the country.

Mr Khorshidi, 43, a high school teacher who, like many others in the ancient city of Isfahan, still spends most evenings on the river’s banks, recalled how 10 years ago he swam in the river with friends and got his lifeguard licence here.

“In the old days, the banks of the flowing river were the centre of all social and economic activities in the city,” he said. “We grew up with this river.”

Now the river, which flowed for 400 kilometres from the Zagros mountains in the west through parks and under Safavid-era bridges and was known for its fertile fishery, have been replaced by dirt and stones. The only evidence of that it was once a great waterway are paddle boats docked on its dusty banks.

The fate of the Zayandehrood is one facing many other waterways as Iran, an arid country, grapples with a water shortage so serious that officials are warning about the possibility of rationing in the capital Tehran, home to approximately 14 million, and other major cities. Iran’s energy minister Hamid Chitchian told parliament last week that climate change, droughts in the past 10 years, wasteful irrigation practices, high consumption and the depletion of groundwater supplies were major factors in Iran’s growing water shortage.

Mr Chitchian said Iranians consumed 96 billion cubic metres – 80 per cent – of its available renewable water resources annually. He said this was 20 per cent higher than the level beyond which a country is considered to be facing a water crisis.

Underlining the severity of the problem, Ali Kayvani, a water resources and irrigation engineer in Isfahan, said the Zayandehrood had never run dry before.

“People blame different reasons for causing the river to dry, but obviously the main reasons are noticeably less rainfall and wrong irrigation plans by authorities.”

Other major lakes and rivers have been drying up and more than 517 Iranian cities and towns are also experiencing water shortages, leading to disputes over water rights, demonstrations and even riots.

“When the river dried, irrigation channels in the province ran dry and agriculture came to a standstill, which resulted in the abandoning of many villages,” Mr Kayvani said. “Many farmers protested several times, asking for government help, and later some of them migrated in search of water.”

The water office in Isfahan has said more than 54 towns in the province will face rationing this summer.

Many people in Isfahan blame badly planned dam construction following Iran’s 1979 revolution as the main factor in the river’s disappearance. The Zayandehrood, too, was dammed in its upper reaches, creating a reservoir that is reported to be currently at a fraction of its capacity. However, many believe the central government diverted the river’s flow to provide water to drier provinces nearby such as Yazd and Kerman, as part of its environmental mismanagement in the country.

But the problem has been compunded by decreasing rainfall. According to Mr Chitchian, Iran’s average annual rainfall has dropped to 242 millimetres from 250mm a decade ago.

Other rivers in Iran, such as the Karoun in the south-western province of Ahvaz, are also at risk of drying up.

In north-west of Iran, near the Turkish border, Lake Urmia, once the largest lake in the Middle East, now holds just 5 per cent of its original volume, while Hamoun Lake, in the Afghanistan border region, was dry for more than a decade until recently.

Both lakes have been the subject of government plans and promises to restore their water.

The lack of water flow into Urmia, which as a saltwater lake was never suitable for drinking or agricultural use, has caused environmental damage and affected wildlife such as migratory birds. More than 95 per cent of the lake has gone dry over the course of almost two decades and officials believe it will take even longer to revive it.

But Parviz Kordovani, an expert on Iran’s environmental issues, is opposed to plans to revive the lake, which include channelling water from alternative sources, because he believes it would be impossible.

“Iran doesn’t have enough water to begin with, so the idea of filling the lake from other water sources is disloyal to the country’s farmers,” said Mr Kordovani, a pioneer in Iranian eremology, the study of deserts.

Hamoun Lake, the sole source of water for the south-eastern province of Sistan and Baluchestan, bordering Afghanistan, dried up during a three-year drought experienced in both countries from 1998 to 2001. Rainfall last winter in Afghanistan has replenished the lake to about 10 per cent of its capacity.

In a recent visit to the province, the Iranian president Hassan Rouhani said the water shortage in Sistan and Baluchestan was one of the main topics in a meeting with his Afghan counterpart, Hamid Karzai, as the lake is fed by the Helmand River in Afghanistan.

As the water crisis grows, Mr Rouhani has made it a top priority, promising “environmental and political plans to bring the water back”.

The president said his administration will spend some of the money saved from reduced subsidies on ways to alleviate the water crisis.

But Mr Kordovani believes the task will be far from easy, and state efforts to address the problem may be too late.

Iran will suffer shortages in water supply “even if the amount of rainfall in the country increases 20 per cent in the next 20 years”, he said.

foreign.desk@thenational.ae