GAZIANTEP, TURKEY // A barrel bomb from a Syrian army helicopter plummets to earth but, instead of exploding and killing scores, it bounces and spins to a stop, the first sign this is not what it seems.

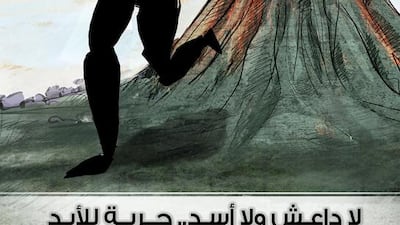

Dwarf-like ISIL fighters grab the barrel and roll it to a fortified compound as sinister music swirls, tiny feet pitter-patter and a black ISIL banner flutters overhead.

These are images from No Difference, an animated short film produced earlier this year by a group of young, award-winning Syrian refugee artists.

Abdullatief Al Jeemo, Amjad Wardeh and Wael Toubaji are known and loved in Syria, where they helped pioneer the use of satire against the regime of Bashar Al Assad.

More recently, recognition from the Cannes film festival, Harvard University and leading galleries in Beirut, Istanbul and London has enhanced their reputation across the broader art world.

“These are brave men with a brave message,” said Dr Tim Benson, editor of the yearly Best of Britain’s Political Cartoons and a global expert on the subject.

“These cartoons offer simple but clear themes, gutsy if not reckless to the extreme considering where they’re working”

All graduates of Damascus University’s faculty of fine arts and all in their 30s, Jeemo, Wardeh and Toubaji also have in common a risk-taking mentality and opposition to the Al Assad family’s 43-year-rule of Syria.

Their recent satirical strikes against ISIL evolved from the ashes of the peaceful 2011 uprising against Mr Al Assad’s government. By 2012 the revolution morphed into a civil war, which has so far displaced nearly half of Syria’s population and left almost 200,000 citizens dead, according to the United Nations. In the past year, the extremist militant group has emerged and enforced its brutal ideology on areas of Syria under its control.

Jeemo’s hometown of Jarabulus, in the north, fell to ISIL in January. He received death threats on social media soon after.

“I made a 100-metre wall painting there commemorating the revolution,” Jeemo said. “ISIL repainted it black.”

Confronting the Islamist group required several delicate steps, the first of which was navigating religious sensitivities.

“The way ISIL manipulates Islam is extremely nasty,” said Wardeh, who uses a nom de guerre. “If we burn their flag in a cartoon, they’ll say we’re burning the flag of the Prophet Mohammed.”

There is also ISIL’s heavy use of quotes from the Quran to support their gruesome beheading propaganda, battlefield crimes and outlandish claims. “They especially attack art,” Jeemo said. “They see art as sin and artists as kafir [unbelievers].”

To dismantle ISIL’s myth, they targeted the group’s extremism and criminality. News from the city of Raqqa, which fell to ISIL last year, included public whipping and executions, shopkeepers forced to veil mannequins and a ban on music. The artists’ satire quickly incorporated these themes.

Some subjects were especially delicate, particularly the August murder of US journalist James Foley, which allegedly occurred in the hills outside Raqqa. Jeemo honoured Foley with by portraying the beheading of the Statue of Liberty – the death of freedom.

Another major issue was denouncing ISIL but not mimicking Mr Al Assad, who constantly condemns terrorism. “Sometimes we argued ISIL kidnapped the revolution,” said Wardeh. “Assad would never have said that.”

No Difference, with its absurd dwarfish ISIL fighters, reasons there is no difference between ISIL and the Al Assad regime. “They both seek to destroy Syria by killing innocent civilians,” said Toubaji, the film’s writer and director .

The film ends powerfully. After an ISIL suicide bomber explodes, a woman greets him in heaven. She soon morphs into Satan and tosses him to hell. “ISIL does not represent Islam,” said Toubaji. “They represent violence. You critique the violence by making it childish.”

The Syrian war has been both a blessing and a curse for freedom of expression. Not long after the 2011 uprising began, a wave of Syrian artists moved to Beirut and added their talents to the creative surge inspired by the Arab Spring. Inside Syria, however, the scene was much more dangerous.

In August that year masked thugs dumped Ali Ferzat, one of the Arab world’s most famous cartoonists, in a Damascus ditch, alive but with hands broken.

The 63-year-old Syrian, who previously received death threats from Saddam Hussein, had turned his pen on Bashar Al Assad, depicting the president trying to catch a ride with deposed Libyan leader Muammar Qaddafi. “Of all the arts, cartoons stand on the front line against dictators,” Ferzat told Britain’s Guardian newspaper.

During those tense days, Jeemo, Wardeh and Toubaji mostly worked at night. They knew each other but worked independently, publishing subversive cartoons, short films and sprayed anti-Assad graffiti and street art on the walls of Damascus.

They were soon wanted by the mukhabarat, Mr Al Assad’s intelligence service. Wardeh learned he had been banned from leaving Syria. Police raided safe houses where they stayed. They all experienced the death of friends and fellow revolutionaries.

The three eventually escaped Syria, first travelling briefly to Beirut. Last year they found themselves together in Istanbul, a hotbed of the Syrian opposition. They began to collaborate. In terms of mocking Mr Al Assad, they were well equipped.

As Damascus University art students they had been required to paint the Al Assad family. The Syrian leader’s profile also helped. “Caricaturists always exaggerate,” said Jeemo. “For me, Assad’s nose is important. In Arab culture, and Syrian culture specifically, the nose symbolises arrogance.”

Over the months, Mr Al Assad’s rhetoric contradicted the carnage and they stretched his nose to Pinocchio proportions.

Their work soon began reaching a wide audience. Al Jazeera and Al Arabiya chat shows featured it, as did Syrian and Lebanese newspapers. It travelled deep into Syria via underground magazines, propaganda posters and revolutionary social media.

“Great art transcends political boundaries, religious differences, cultural differences, even language itself,” said Andrew Farago, curator of the Cartoon Art Museum in San Francisco.

“These artists should be commended not only for their skill, but for their bravery.”

A high point came in December last year when Jeemo and Wardeh had a cartoon collection published in Istanbul. The cover featured Mr Al Assad snorting a line of debris from bombed buildings like cocaine.

“By then, the destruction was beyond our imaginations,” said Wardeh. “Assad was addicted to turning our cities to dust. That was his cocaine.”

At the end of the year, Wardeh created a Christmas cartoon so dark that Reuters and several leading Arabic newspapers covered it. A former US official told The National he saw it in Washington during a hearing on Syria.

The work showed an explosion in the shape of a Christmas tree with the message “Bashar Al Assad wishes you a merry Christmas”. The next day, a modified version of the cartoon appeared online with a beheading beneath the tree and a new message: “ISIL wishes you a merry Christmas.”

foreign.desk@thenational.ae