Two cases of child rape have triggered the biggest displays of public anger over sexual violence in India since the 2012 gang rape and murder of a young woman in Delhi.

The protests over the past week have been directed against Prime Minister Narendra Modi's Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which has been accused of protecting the rapists from justice, and Hindu nationalist groups allied to the BJP.

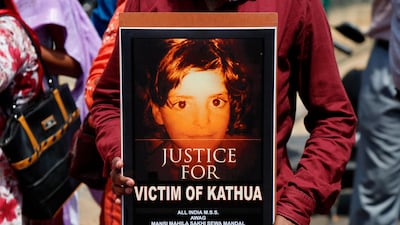

The details of the two rapes emerged only over the past week. In Kashmir in January, an eight-year-old Muslim girl was raped and murdered in a small village temple over the course of three days. Eight Hindu men, including a former bureaucrat and four police officers, have been charged with crimes ranging from rape and murder to complicity in covering up the incident.

On Monday, as police tried to file charges against the men in the town of Kathua, local lawyers shouted Hindu nationalist slogans and tried to block investigators from entering the courthouse. BJP ministers in Jammu and Kashmir state's coalition government attended rallies in support of the accused that were organised by the Hindu Ekta Manch, a nationalist group.

Separately, a BJP legislator in the state of Uttar Pradesh, Kuldeep Singh Sengar, was arrested on Friday by federal investigators, after being accused of raping a 16-year-old girl last year. The state's BJP government had transferred the case to the federal Central Bureau of Investigation under public pressure last week after local police dawdled for months over the investigation.

The legislator’s brother, Atul Singh Sengar, was arrested earlier in the week for assaulting the girl’s father on April 8. The father died in hospital of his wounds last Monday.

The evident reluctance to punish these crimes was compounded by Mr Modi’s silence despite growing public outrage. A BJP spokeswoman on Friday accused the opposition of politicising the crimes, and wondered why candlelight marches and protests had not been organised over the case of a 12-year-old girl who was raped and then burned alive in the state of Assam last month.

Mr Modi finally addressed the issue on Friday evening, saying that “no culprit will be spared, complete justice will be done. Our daughters will definitely get justice.” The two BJP ministers in Kashmir who attended the rally in support of the accused rapists were forced to resign.

The rape cases in Kashmir and Uttar Pradesh have shaken India in a way that has not been witnessed since the December 2012 gang rape, and they have served to highlight how little has changed on the ground since those protests.

In the wake of that crime, India’s laws against rape and sexual assault were strengthened. Rapists today face prison sentences ranging from 20 years to life. A government set up a fund of roughly 30 billion rupees (Dh1.68bn) to improve the safety of women in public places. Policemen who fail to register rape complaints are liable to be jailed for up to two years.

Between 2012 and 2016 – the last year for which government data is available — the number of rapes registered annually by the police rose from 25,000 to 40,000. Roughly 19,000 of the 40,000 rapes in 2016 were of children.

The statistics do not necessarily reveal a rise in the incidence of rape, said Jayshree Bajoria, the author of a Human Rights Watch (HRW) report last November on sexual violence in India. Rather, the numbers may equally indicate a rise in women coming forward to report rapes, she said.

But the measures introduced after 2012 have failed to change many realities on the ground.

In an investigation of 21 rape or sexual assault cases last year, Ms Bajoria found that policemen frequently resistant to women who wish to file complaints. In cases where the rapists were politically powerful, or came from a dominant community, officers often encouraged the women to “compromise” or move on.

So far, not a single police official has been charged for failing to register a rape complaint. “To hold the police accountable has been a perennial problem, and not just with rape,” Ms Bajoria said. “We just don’t see action taken against the police.”

Further, as of February, only 8.25bn rupees of the 30bn rupees in the women’s safety fund have been spent, the government said.

“We tend to think that after these new laws, we’ve made progress — and we have, on paper,” Ms Bajoria said. “But when it comes to ensuring that women get the kind of justice they deserve, there are still serious gaps.”