CHITWAN, NEPAL // Six years ago, Januka Dhamala Sandhya abandoned her university degree and left home to join Nepal's guerrilla Maoist army, ready to take up arms for a cause she believed would lead to the emancipation of women. "People were very oppressed, but women were doubly oppressed - by the state and society - so I realised that the Maoists and the Peoples' War that they were fighting was the only way that Nepali women could be liberated."

In May last year, it seemed Ms Sandhya would get her wish: the country voted in a referendum to abolish the 239-year monarchy and emerged a republic with the Maoists heading a new government. That was the result of a peace pact agreed in late 2006 between political parties and the rebels, who pledged to end their decade-long violent struggle - a conflict that had killed 13,000 people - in return for political representation and the referendum.

But, two years on, and little progress has been made on healing the scars from a decade of brutal war - symptomatic many analysts say of the political and ideological bickering that continues in the government halls of Kathmandu. At issue is what to do with the 19,000 Maoist fighters who were moved into 28 UN-administered camps across the country where they were supposed to be disbanded, rehabilitated and reintegrated back into society.

Maoists want their fighters to join the military, but the opposition Nepali Congress is apprehensive about merging them with the army ? which grew on the need to fight the communist rebels. Earlier this month, the government formed a committee, for the second time, to begin the process of integration, but with the army objecting to any recruits with political leanings, the task could take longer than its six months target.

The UN secretary general, Ban Ki-moon, has said the rehabilitation of former fighters is the single biggest challenge facing the new government and has pledged to extend by another six months from today the UN mission tasked with helping to oversee the process and the monitoring of arms. "It is clear that the United Nations, if it is not to risk jeopardising the peace process, cannot immediately terminate the support it has been providing through UNMIN as requested by the government of Nepal," Mr Ban said after a trip to Nepal late last year.

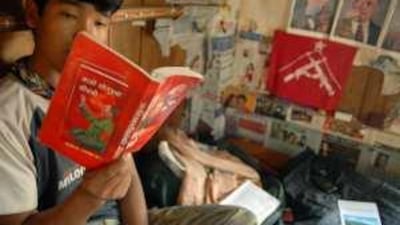

"But neither can the United Nations be expected to maintain indefinitely the monitoring of arms and armed personnel while the process for deciding the future of the former combatants is further delayed," he said. In the meantime, there is growing restlessness in the camps, where commanders keep a close eye on their recruits who continue to receive military and ideological training. Bhaktabahadur Thapa, a 21-year-old People's Liberation Army fighter, joined the insurgency at 16, leaving the comfort of his parents' home and donning the ill-fitting fatigues he still wears today.

"I joined the fight for the proletariat," he said, his unit commander nodding approvingly behind him. The setting for division headquarters in Chitwan, in this rural part of Nepal borders on idyllic. From the road, the camp could be mistaken for a bungalow-style inn, save for the armed guards prohibiting entry to most non-PLA visitors and the prominent hammer and sickle at the camp's entrance. Facilities, financed by the government and international donors, have improved and the tents they were once confined to have been replaced by wooden houses with running water and electricity, a luxury not enjoyed by most villagers in the impoverished area.

While they receive a decent monthly wage of 5,000 Nepalese rupees (Dh250) and a daily food allowance, combatants resent being restricted to one place. "We used to travel a lot but here we don't get to travel. We don't go to the people, we don't even get to talk to them," Mr Thapa said. "Obviously some [PLA] members are a little bit agitated that nothing has been happening. The process is not going in any direction so this is making them restless, but they are not discouraged and not giving up," said Biyog, a brigade commander at Chitwan, where 1,800 former soldiers are based.

Aastha Indira is a picture of modesty in her faux pearls, pink cardigan and black trousers. But ask the 23-year-old about what should happen to the former combatants and it becomes clear why she is a battalion vice commander. "I don't want to leave this cantonment camp for myself as an individual. If it's integration of the whole PLA then we are ready to go as soon as possible," she said. Ram Saran Mahat, a member of the opposition Nepali Congress, said the Maoists were continuing to recruit fighters and those in the camps were receiving training.

"They are maintained by the government, they are given monthly allowance from the taxpayers' money, but they are still getting political and ideological training by their party, which is a serious issue because the conflict is over," said Mr Mahat. "They have renounced violence but the Maoists are maintaining these camps in a certain manner that conflict is still on and they are preparing for a major offensive."

Rhoderick Chalmers of the International Crisis Group said there could be no progress on peace without a complete renunciation of violence by the Maoists. "You can't really be sure that you are out of an armed conflict until you no longer have two standing armies that were formally at war with one another. It has to be part of the logical conclusion [to the peace process]," he said. * The National