A study of a primordial South African skeleton cast new light on how the human brain evolved, the types of food hominins ate and the hardships and diseases prevalent in earth's Pliocene epoch.

Little Foot is a skeleton fossil of a young adult female who inhabited South Africa 3.67 million years ago during a critical juncture in our evolutionary history.

Her name reflects the small foot bones that were among the first elements of the 1.3-metre skeleton to be found when she was unearthed from a cave in the 1990s.

Such habitats provide a fruitful seam for archaeologists, with Australian researchers finding a two-million-year-old male Paranthropus robustus skull in the Drimolen caves in November last year.

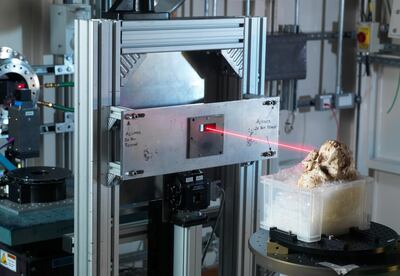

Scientists spent more than 20 years reassembling Little Foot and on Tuesday revealed insights gained from a sophisticated scanning of her cranial vault – the upper part of her braincase – and her lower jaw.

"In the cranial vault, we could identify the vascular canals in the spongious bone that are probably involved in brain thermoregulation – how the brain cools down," said University of Cambridge paleoanthropologist Amelie Beaudet, who led the study published in e-Life.

The information marks a scientific breakthrough and Ms Beaudet said the cooling system probably played a key role in the threefold increase in brain size from early hominins to modern humans.

Little Foot's teeth were also revealing.

"In the teeth we could see tiny structures that suggested she had to face a very stressful situation at some point in her life," Dr Emily Tilby, principal investigator at the University of Cambridge's archaeology department, told the BBC's Today programme.

"And that's probably because she was finding food in arduous environments, or maybe she was sick at some point, and this kind of information can be recorded in the teeth."

Scientists were also able to form hypotheses on the kind of food she was eating. In the case of Little Foot and other fossils of her species, the predilection was for hot food – temperature-wise not spice-wise.

"This is something that we can explore more in the future because we have data on the bone structure – and that will be really helpful to reconstruct diets to say precisely what she was eating," Ms Beaudet said.

Little Foot's species – Australopitheci – blended ape-like and human-like traits and is considered a possible direct ancestor of humans, although Little Foot's precise age is not yet determined.

"Australopithecus could be the direct ancestor of Homo – humans – and we really need to learn more about the different species of Australopithecus to be able to decide which one would be the best candidate to be our direct ancestor," Ms Beaudet said.

What Little Foot previously revealed about primordial life

The findings build on previous research on Little Foot.

The species was able to walk fully upright but had traits suggesting it also still climbed trees, perhaps sleeping there to avoid large predators.

It had gorilla-like facial features and powerful hands for climbing. Its legs were longer than its arms, as in modern humans, making this the most-ancient hominin known to have that trait.

"We really hope that we can combine all of this evidence and then try to understand better how she was living more than two million years ago in Africa," Ms Tilby said.