One of the loudest voices raised in support of Darfur has been George Clooney's. He is one of a number of American stars, including Angelina Jolie, Mia Farrow and Macy Gray, who have been working to raise the profile of this crisis. Their actions have been met with cynicism in the Middle East and in Sudan. "Hollywood celebrities think they can come and be famous by claiming they support the people of Darfur," said one of the president of Sudan's advisers.

Whatever their motives, Clooney and co are at least doing something. Middle Eastern countries, by contrast, have shown a shameful lack of interest in the suffering of the Darfuris. The nation's crisis began just as the 20-year conflict between northern and southern Sudan looked to be coming to an end. Rebel groups in Darfur began attacking government targets, accusing Khartoum of oppressing "Black Africans" in favour of "Arabs".

The language of race used to describe the conflict has been virulent, and evoked rather simplistic passions. In the West race is a sensitive issue, which may be one reason why Darfur has become a pet cause of Hollywood stars. By the same token however, the apparent indifference of Middle Eastern countries may be because they consider Darfur to be a tribal or "black" issue. But the conflict is not about race: closer analysis reveals that it began as a dispute over tribal lands between the nomadic tribes, referred to in shorthand as "Arab", and the permanent farmers, referred to as "African".

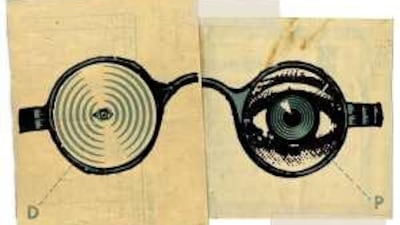

Famine, drought and changing land usage led to clashes about territorial rights which have yet to be resolved. In addition, Darfuris became increasingly angry at the low level of services they received from the government by way of water, sanitation, health care and education and felt they had been left out while the government focused on Khartoum and the south. I went to see Darfur with my own eyes at the end of last year. In the camps outside Al-Geneina, the capital of West Darfur, I saw families living in tents no more than three metres square, with rationed food and water.

Aid agencies were doing their best, but the Sudanese government is not keen on their presence and, with the crisis into its sixth year, donors are growing weary. At one school I visited, scores of fidgeting youngsters dressed in white stood under the midday sun facing inwards to a small centre stage where their head teacher led them in vibrant song. Their joillity belied the pain many had endured, especially those old enough to remember the bloodshed, fear and crisis that began in 2003. I spoke to two young girls.

"I'd like to become a lawyer when I'm older," 16-year-old Fatima told me. "I want to be a writer," said her friend Layla. "Why?" I asked. "To make our country better," said Fatima. "So it doesn't happen again," said Layla. From Darfur, I went on to Cairo, Jeddah, Riyadh and Doha to highlight its plight. In these Middle Eastern cities, however, people were strangely angry that the conflict in Darfur was being raised as an issue. "What about Palestine? Why aren't you talking about Palestine?" they said.

But the oppression in Gaza and the West Bank does not outrank the suffering of Darfur, or vice-versa. Suffering is suffering wherever it takes place, and must be spoken about, fought against and stopped, no matter who the perpetrator, no matter where the location. Why should the suffering of Darfuris be diminished? Human hearts are big enough to remember and mourn the plight of many, not just one.

More than 1,400 people were killed in Gaza during Israel's recent onslaught, an event that can only be described in lay terms as a contained massacre, part of more than 60 years of killing and suffering. In Darfur too, the numbers are heart-wrenchingly high. According to the UN, 300,000 people have been killed since the crisis began, a further 2.7 million people have been displaced from their homes, and five million people are living on aid. It makes for grim reading. Khartoum puts the figure of those killed closer to 10,000.

Whatever the number, the crisis is real, and the lack of instinctive empathy concerned me. It was as if people did not want to believe that such brutality could happen in another Arab Muslim country. Darfur is a complex issue, but this should not stop any movement for sympathy and aid to support the human beings who are suffering daily. Middle Eastern countries, Arabs and Muslims, need to step up and start contributing to the aid effort. If they are serious about relieving suffering, then first they need to contribute financially. The amount donated so far has been pitiful, and has gone straight into the hands of the Sudanese government.

In addition, the Middle East needs to contribute human resources by training and dispatching more aid workers. In terms of taking an active role in negotiating peace, Middle Eastern failures abound both for Palestine and Darfur. Only the recent Qatari initiative for peace in Darfur appears to have a measured, sustainable - and dare I say it - hopeful glimmer. Last month the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued a warrant for the arrest of the Sudanese president Omar al Bashir on charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity. Many Darfur campaigners questioned the wisdom of such a move, fearing it would hamper their own efforts to resolve the crisis, especially when Sudan was moving with democratic elections and the Qatari initiative looked hopeful.

Mr al Bashir in response called the ICC "undemocratic", accused it of "double standards" and expelled 13 aid agencies from Darfur. In defiance, he attended the Arab League summit in Qatar last weekend, which rejected the ICC warrant. "No Arab president will be let down," said a statement. "We are going to fight until the end." The ICC along with aid agencies are seen to be pursuing a biased western agenda, leading Arabs to instinctively side with the Sudanese government without any real assessment of the situation. What Sudan actually needs is not blind support, but critical friends. For the Middle East and for many Muslims, the contrast in approach to Darfur and Palestine is revelatory. Darfur is complicated.

Darfur means disentangling the moral rights and wrongs of all parties who are Muslim, and bluntly put, there is not the moral fibre nor the political will to do so. Palestine is a simple moral judgment - them and us. The oppressor and the oppressed are clear, and the swell of public opinion is in one direction, making it easy to shout and protest. Both conflicts are horrific and are taking a huge humanitarian toll. Each life lost is a loss to all humanity, whether it be in Gaza, Darfur or elsewhere.

We must reach through the complexities of the political situations and apply universal moral standards. Only then will we be able to identify where in the conflict lies justice and ultimately peace. To have the credibility and moral authority to do so, we must show an even and compassionate hand no matter where or against whom the suffering is being perpetrated. When Clooney visited Darfur in 2006 as a reporter, he was accompanied by a man who is now president of the United States.

At that time Barack Obama said: "If we care, the world will care. If we act, then the world will follow." President Obama is sticking to his message. Last week he sent his envoy Scott Gration to kick-start peace talks between the Sudanese government and the rebels. It is part of his wider outreach to the Middle East. The time has come for the Middle East to reach out as well. An important first step will be to focus on achieving peace in Darfur.

Shelina Zahra Janmohamed is a British writer and blogger. She is also the author of the book Love in a Headscarf, a humorous memoir of growing up as a Muslim woman.