We’ve all done it – binned a tablet with a cracked screen, ditched an increasingly sluggish iPhone overshadowed by the latest model or junked a TV seemingly rendered redundant by the promise of a sharper picture on a next-generation set.

But while we’re becoming much better at recycling paper, glass and plastic, our fast-moving digital culture, coupled with increasing affluence and consumer hunger for the latest gadgets, is creating a global epidemic of domestic electronic waste that too few governments are addressing and which is threatening to get out of hand.

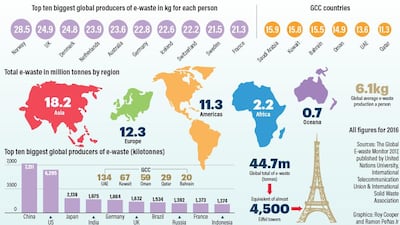

According to a recent study by the United Nations the world as a whole produced 44.7 million metric tonnes of so-called “e-waste” in 2016. That’s a pretty meaningless figure – until you picture it, as the UN suggests you might, as the equivalent of 4,500 Eiffel Towers.

And it's only going to get worse. According to The Global E-waste Monitor 2017, a joint report by three UN bodies, in 2014 each person on the planet was responsible for the equivalent of 5.8kg of e-waste. By 2016 that had increased to 6.1kg and by 2021 is forecast to reach 6.8kg – a grand total of 52.2 million metric tonnes (or, if you prefer, 5,200 Eiffel Towers).

This matters, says the UN, because the “improper and unsafe treatment and disposal” of e-waste “through open burning or in dumpsites, pose significant risks to the environment and human health”, and “also present several challenges” to the achievement of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

“The growth in electronic waste kind of came up and bit us from behind, that’s for sure,” says Stuart Fleming, chief executive of Enviroserve UAE, which is about to open what it bills as “the world’s largest integrated e-waste and specialised waste recycling facility” in Dubai Industrial City. “The thousands of tonnes of e-waste in landfills throughout the world, dumped throughout the Eighties and Nineties, must be amazing.”

Vanessa Gray, one of the authors of the report, agrees that while we’ve been busy getting our heads around the recycling of paper, glass and plastic, the issue of e-waste has crept up on us largely unnoticed – but says now is the time for individuals, companies and governments to act.

“There are more computers, smartphones, data centres and networks and the amount of electronic waste – anything that runs on a battery or a plug – is really growing,” she says.

The UN report, published in December, says that “disposable incomes in many developing countries are increasing and a growing global middle-class is able to spend more on electrical and electronic equipment”. It is, says Ms Gray, “great that the information society is growing, giving access to more information to more people. But at the same time it also creates a lot more electrical and electronic equipment and more e-waste.”

In the end, she says, “consumers have an important role to play, because we cannot continue to consume like we are at the moment, not using things until the end of their lives, throwing them away and not recycling them properly”.

Consumers are, of course, influenced by canny marketing, and the report also points a finger at the sales ploys adopted by technology companies. Many people, it says, own more than one information and communication technology device, “and replacement cycles for mobile phones and computers, and also for other devices and equipment, are becoming shorter”.

If this sounds counterintuitive, it is: improving technology should increase the lifespan of devices, not reduce it. But, as users of a range of products have discovered to their cost, built-in obsolescence is a cynical reality of the modern electronics industry. In December Apple admitted that its regular software updates slowed down the performance of its older iPhones, and the company is now being investigated by the consumer protection agency in France, where built-in obsolescence designed to generate sales is a criminal offence.

The e-waste report, by the United Nations University, UN information and communication technology agency the International Telecommunication Union and the non-profit International Solid Waste Association, singles out the UAE as having “one of the world's lowest life expectancy of electronics and high amounts of consumption, making the country produce substantial amounts of electronic waste annually”.

But on the surface, at least, this seems like a harsh verdict.

In terms of the volume of e-waste generated by each individual in the country, the UAE compares very favourably to the ten worst performers in the world – a table dominated by nine European countries and Australia. In 2016, says the report, the UAE produced 13.6kg of e-waste per person, compared with 28.5kg in Norway, the nation in the number-one position. The UK, with 24.9kg, was second worst, followed by Denmark (24.8kg) and The Netherlands (23.9kg).

According to the report the UAE also performs better than all but one of its fellow GCC members. The worst offender in the region is Saudi Arabia, which generated 15.9kg of e-waste per person in 2016 – still relatively low compared with many European countries – followed by Kuwait (15.8kg), Bahrain (15.5kg) and Oman (14.9kg). The UAE’s output per person (13.6kg) is bettered only by that of Qatar (11.3kg).

But there are two significant limitations with these figures, which suggest the situation in the UAE and, perhaps, the entire Gulf region, may be far worse than at first appears.

Only 41 countries were able to provide the report’s authors with firm data about the amount of e-waste generated – and none of the Gulf states, including the UAE, was among then. For such countries the volume of e-waste was estimated, based on data from those nations that did submit records.

“We found a strong connection between the amount of disposable income people have and the amount of electronic and electrical goods they will purchase and, therefore, the amount of e-waste produced,” says Ms Gray, an information and communications technology expert with the UN’s International Telecommunication Union. The report’s estimates are, she says, “relatively good, though of course we would much prefer for countries to provide these data”.

________________

Read more:

Recycling company Averda disposes UAE's e-waste

New electronics recycling plant in Dubai to help eliminate toxic waste

Growing problem of e-waste can only be addressed by more awareness and recycling

________________

One of the objectives of the report, she says, is to persuade more countries to start collecting this information: “This is really the first step to addressing the challenge, because if a country doesn’t know how much e-waste it has, it can’t start producing relevant policies.”

The other problem is that the figure for the amount of e-waste produced by each person in the UAE is based on a total population of about 9.8 million. But workers from countries such as India and Pakistan account for more than 50% of this number. Given that they will be earning far less than either Emiratis or western expats, and that the vast majority will be sending home the bulk of their salary, it isn’t unreasonable to suggest that only half of the 9.8 million population is likely to have sufficient disposable income to be in the market for electronic goods.

If so, the UAE’s output per person is likely to be at least double that in the report – not 13.6kg, but over 27kg. In that case the UAE would be threatening Norway’s position at the very top of the table of nations with the highest per-person output of e-waste in the world.

Nevertheless, the report also singles out the UAE for praise for plans, now nearing completion, to set up the region’s first dedicated e-waste recycling plant. This, says Ms Gray, “is a very important and very good step. Today 66 per cent of the world’s population is covered by e-waste legislation, but only have 20 per cent of e-waste is being properly recycled. So while legislation is one of the necessary steps, we need to go beyond that and implement change – we have to have these recycling plants.”

Investing in such plants isn’t viable for small countries, she says, but they can export e-waste to countries that do have them, and that means that “this recycling plant in Dubai is great not just for the UAE but for the whole region”.

The new plant means the UAE is at the vanguard of a new chapter in the war on environmental harm. Last week the government of Hong Kong, whose population of 7.4m people each produced 19kg of e-waste in 2016, opened its own US$54m (Dh198m) e-waste recycling plant to tackle the problem.

The company behind the Dubai initiative is Enviroserve UAE, whose Green Truck recycling collection lorries are already familiar in the emirate. With dismantling plants and agreements in countries including GCC neighbours, Georgia, South Africa, Rwanda, Kenya, Angola, Nigeria and Egypt, what Enviroserve is calling its “recycling hub” will be handling e-waste from a large part of the Middle East and Africa.

Stuart Fleming, the company’s chief executive, says construction of the Dh120 million plant in Dubai Industrial City is almost complete and installation and commissioning of the specialist equipment is imminent. “We are looking to move in in April and soft launch through the summer, with an official opening in September”.

Funding for the plant has come through the Swiss Government Export Finance Agency, “which makes this the largest foreign direct investment in the environment in the UAE”. When fully operational the Dh120 million plant in Dubai Industrial City will have a capacity of 39,000 tons of e-waste a year, in addition to handling 60,000 tons of other specialist waste, ranging from expired consumable products, such as shampoos, to car parts.

The automated technology, says Mr Fleming, “is state-of-the-art, and there’s nothing like it in the rest of the Middle East, let alone alone the Middle East-Africa region, which is our core territory”. The company has rejected chemical and high-pressure-water techniques as environmentally unfriendly, instead opting for a technology that combines shredding and pulping with magnets and air pressure to separate and extract steel, iron, copper, zinc, nickel, gold and silver and precious metals.

The UN is keen to point out to companies and governments alike that, as well as protecting the environment, recycling e-waste also makes sound economic sense. Burying or burning e-waste is to throw away valuable component materials including precious metals.

The UN report estimates that the global value of all raw materials in e-waste in 2016 was an astonishing 55 billion Euros (Dh250bn) – more than the GDP of many countries.