Capt William Shakespear died exactly 100 years ago, in a battle between rival Saudi armies. No, not that William Shakespeare, but this story is just as remarkable as any play.

Captain Shakespear of Arabia

“Bin Saud was riding a horse, but Captain Shakespear was on a camel. One day before the fighting Bin Saud and his son, Turki, told the Sahib that he should not accompany them to the battle but had better either go to Qasim or to Zilfi where they would meet him after finishing the fighting.

“Sahib did not agree and said it was dishonourable for him to turn back, and that he would accompany them in the battle ...”

So the news of the death of William Shakespear, British army officer, at the Battle of Jarrab on January 24, 1915, was relayed by his cook, Khalid bin Bilal of Zubair. It was recorded four months later at the Political Agency in Bahrain.

This other Shakespear, whose century-old grave and tombstone remarkably survive in downtown Kuwait city, never achieved the fame of his famous playwright namesake, who spelt his name with an extra “e”. Yet his life was remarkable, as were his talents.

Born on October 29, 1878, in Bombay in British India, Shakespear was also a diplomat, photographer, explorer, and an amateur botanist and geographer.

Among the local Arab Bedouin he was called ‘gonsool skaykh-speer’, and referred to as “brother” by Emir Abdulaziz Al Saud, the future king of a country named after him, Saudi Arabia.

The man who “came like a whirlwind”, as described by biographer Victor Winstone in his 1976 book Captain Shakespear, was killed 100 years ago at Jarrab, north of Al Majma’ah.

Even in his last hours, Shakespear was taking photos. He was last seen carrying his camera to a patch of higher ground to capture scenes of battle between Al Saud and forces of Al Rashid, a rival contender for Najd.

His body was found several days later, marked by three gunshot wounds.

Even though he died young, at 36, he had left his mark. An explorer who mapped hundreds of kilometres of uncharted areas of northern Arabia, he also took the first photo of King Abdulaziz and his brothers.

Shakespear also drafted the first treaty signed between Ibn Saud and Britain, the first international recognition of Saudi rule in Arabia.

He had in many ways earned himself the title of ‘Shakespear of Arabia’ before his legacy was soon eclipsed after his death with the arrival of another British officer, T.E. Lawrence.

A great linguist, he spoke Urdu, Pushtu, Persian and Arabic fluently. After serving in the army, Shakespear at the age of 26 joined the British Foreign Office in 1904. From 1909 onwards he became a British political agent in Kuwait, making seven expeditions into the Arabian interior, eventually meeting the future Saudi ruler.

Documenting everything in his diary, Shakespear’s record of that meeting in 1910 is believed to be the earliest report of King Abdulaziz through European eyes. Ibn Saud was “a fair, handsome man, considerably above-average Arab height with a particularly frank and open face, and after initial reserve … of genial and very courteous manner”, he wrote.

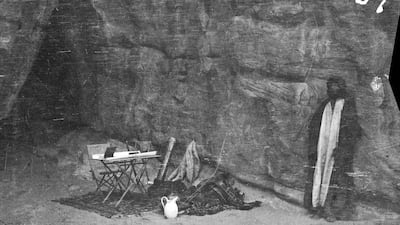

A story from that time tells how Shakespear cooked a meal for the Kuwaiti Sheikh Mubarak and his Najdi guests of Al Saud, with a menu of roasted local lamb with mint sauce, roasted potatoes and tinned asparagus. His political role in forging friendships with Arabian Gulf leaders may have been forgotten, but his collection of photos leave the strongest lasting impression of the man.

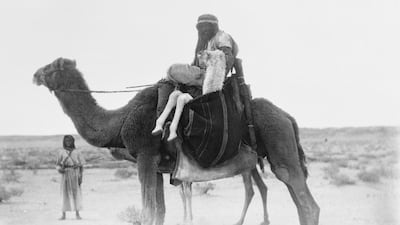

Besides images of the Al Saud family and other important Arabian tribes, there are photos of the landscapes of wadis and valleys, and traditions such as stopping for coffee and transporting baby camels in a sack.

Shakespear’s camel ‘Dhabia’ was photographed several times by her rider along with the army of Al Saud on horses carrying banners on spears.

Unlike Lawrence, who liked to pose in local dress, self portraits of Shakespear capture him in a military uniform. There are also photos of him with his falcon, used for hunting with his pack of desert salukis.

In March 1914, Shakespear began an almost 3000-kilometre journey from Kuwait to Riyadh and on to Aqaba via the Nafud Desert, mapping, photographing and documenting everything in great detail, the first European to do so.

The data he collected were passed on to the geographical department of Britain’s War Office, and his collection of pressed plants given to the Natural History Museum.

In one of his last letters to his brother, on the eve of the battle, Shakespear wrote: “Abdulaziz wants me to clear out, but I really want to see the show and I don’t think it will be unsafe really.”

Photographs by W.H.I. Shakespear via Royal Geographical Society (with IBG)

Text by The National Reporter Rym Ghazal