For more than two years now, Bashar Al Assad's days have been "numbered" and his regime "doomed". Those who have used one or both of these words include the leaders of the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, France, Jordan and Turkey, among many others.

This echoes the language and wishful thinking used about Saddam Hussein; after his days were said to be numbered, he lasted another 12 years. The global dictators' club must feel continually reassured by this hollow rhetoric.

But what happens if, militarily at least, Mr Al Assad prevails? This is the nightmare scenario few dare to contemplate.

About 100,000 people would have died and millions would have had their lives ruined for nothing. Hundreds of square kilometres of some of the most heritage-laden land on the planet would have been despoiled. Freedom, rights and dignity - the founding aims of the Syrian revolution - would be buried in the country's soil.

For the West, and other states that oppose the Assad regime, its survival would be a huge loss in prestige and credibility. Iran and others would see it as another sign of the West's weakness and decline.

The regime is about to launch a furious assault on the already scorched Aleppo, Syria's largest city, which has been under siege since last July. Should the whole of the city fall, how much more would fighters endure before they flee the vastly better-armed regime forces? With Aleppo gone, the city of Raqqa would soon follow. The regime could control all the major urban centres.

Mr Al Assad could never regain the dominance over Syria he had in 2010. Too many would bitterly oppose him; he could never relax or lift his state of fear. But an analysis of just what his remaining in power would entail is instructive.

The regime would be deprived of even the pseudo-legitimacy in which it once cloaked itself. As in the 1980s, after the Muslim Brotherhood uprising against the Baathist regime, there would be a clampdown on all dissenters It would be even more ruthless this time.

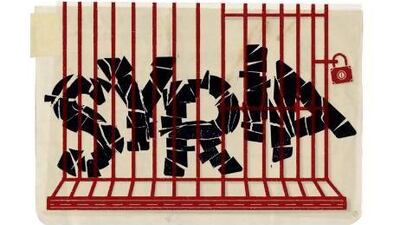

The prisons would not be large enough to hold all his opponents. Many would just "disappear". Civil society groups that have flourished in the turmoil while the regime has focused its attention on armed groups would be shut down and crushed. Political activity, such as it is, would vanish, perhaps for decades.

Even though repression would be preferred to reconciliation, Mr Al Assad would still have to reach out to some communities. Could he make a deal with the Kurds, for example? If they were willing, what would be their price?

How would the regime approach the issue of reconstruction? The monumental smashing of whole urban neighbourhoods means that just clearing the rubble may take years. Someone would have to clear out all the unexploded ordinance that litters Syria's streets and fields.

Some estimate that reconstruction alone could cost from US$80 billion (Dh294bn) to $100bn.

Add to that unemployment that may have risen to 44 per cent. Tourism would take years, even decades, to revive.

Economic revival would be made much tougher if Syria were cut off from the majority of the world's donor community. Russia and Iran alone would be unlikely to fund repairs in addition to the injection of investment to kick-start the Syrian economy.

The regime would also be seeking to rearm, leaving it further at the mercy of its Russian and Iranian patrons, who would exert enormous influence over Damascus.

Then there are the refugees and the displaced people, a combined total at present of over 6 million. The figure that will have risen by the time the fighting ends.

If the regime stayed, the refugees would remain, forming a significant drain on the resources of the host countries and donor communities. As for the internally displaced, would they have homes to return to or safe communities?

Moreover, the regime might not permit displaced people to return, especially to areas that it deemed vital to its security needs near borders, in Homs and close to military targets. This crude demographic engineering would complete the sectarian and ethnic cleansing of parts of the country.

Syria would be isolated, though not cut off. There would be no fixing of relations with the US, the EU and much of the region. Regional powers would - as happened in Iraq - continue to fund and supply opponents, some of whom no doubt would use bombs, kidnappings and other violent actions to disrupt regime control.

What is less commented on, though, is that the challenges facing a victorious regime would be similar to the challenges facing any victorious rebel force. This is because the short-sighted "Assad is the only problem" approach assumes that his removal would fix everything.

His departure would not even end the fighting. In any post-Assad scenario, there would still be reconstruction, reconciliation and the refugee challenges. A new government would have to mend a broken society. Given the anger, reprisals and looting would be inevitable.

Looking at the slow pace of donor commitments at present, could $100 billion be raised for Syria? A new government would face regional foes such as Iran and Hizbollah working to undermine the new system's authority. Non-democratic regimes might not be too keen on a democratic transition either. Forming a government from the ranks of the opposition would have the additional challenge of the factional infighting and power struggles among the myriad groupings and their patrons. Moreover, their regional backers would demand rewards for their support.

In either scenario, the challenges would be immense. Syria would be broken and at risk of fragmentation. Jabhat Al Nusra and other extremist Islamist groups would pose a dangerous threat in either case. Weapons caches would permit sustained aggression against whoever was in power.

A politically negotiated outcome is vital. With an internationally sponsored agreement that has the buy-in of all parties - international, regional and Syrian - the above challenges, while not insurmountable, would become easier.

Reconciliation will be possible if all communities have a stake and do not feel they have lost. Winner-loser arrangements will not work. One reason that Iraq is so badly divided today is that Iraqi Sunnis have felt, ever since 2003, that they have lost.

In a politically agreed scenario, rearmament might not be so essential and there could conceivably be a deal to destroy Syria's chemical weapons stockpiles. Funding would be easier to secure and economic progress feasible. There might be enough left of Syria's state institutions to keep the country running.

Also, Syria might have a chance of being independent, not at the mercy of one particular power bloc or in need of an external patron.

This means all components of Syrian society, including regime loyalists and supportive communities, must be included in any eventual agreement. They must each have a stake in its success. Moreover, with a collective buy in, the extremists on all sides would be defeated.

What Syria needs is the international community to buy into, adopt and implement a coherent political strategy that puts aside narrow domestic political agendas for the sake of ending one of the worst crises to hit the Middle East in decades.

Chris Doyle is director of the London-based Council for Arab-British Understanding