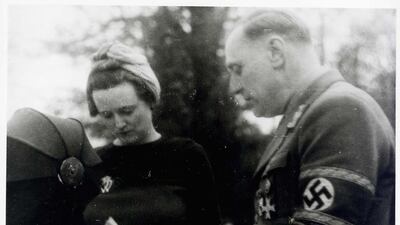

Without trace of remorse, William Joyce, known as Lord Haw-Haw for his supercilious accent during his wartime broadcasts in support of Adolf Hitler, went to the gallows for high treason in 1946, the last person to be tried and executed for the crime in Britain.

The more fanatical of ISIL’s British adherents would undoubtedly welcome the martyrdom of being sentenced to death for the same offence.

If senior UK politicians get their way, the 660-year-old law may be invoked again, to prosecute those swearing allegiance to the Islamist extremists who are Britain’s declared enemies.

No British recruit to ISIL, or similar groups, would face the death penalty. But long jail sentences would inevitably follow; the maximum punishment since treason ceased to be a capital offence in 1998 – three decades after hanging was abolished for murder – is life imprisonment.

This is how Philip Hammond, Britain’s foreign secretary, speaking earlier this month to the UK parliament, put it: “There are a number of offences under English law with which returning foreign fighters can be charged. We have had a discussion about the allegiance question.

“We’ve seen situations of people declaring that they have sworn personal allegiance to the so-called Islamic State and that does raise questions about their loyalty and allegiance to this country … and raise questions about whether offences of treason could have been committed.”

These are precisely the kind of words politicians and voters on Britain’s right want to hear. Having seen hooded men with London or southern English accents gloat over the imminent murders of civilian hostages, or issue chilling threats to their country of birth, they demand a genuinely tough response. And the sheer savagery of ISIL violence means the thirst for counter-attack is growing even among those with different political leanings.

But would it have the slightest effect on the thought processes of people tempted to join the 500 or so Britons already estimated to be fighting with or supporting ISIL in Syria and Iraq?

As a stand-alone measure implemented as a sop to public opinion, it would probably do no more than make vengeance-seekers feel better. ISIL would be proud to have provoked, with its odious butchery, a backlash against expendable volunteers. It would seem to be a new recruiting tool.

Stephanie Merritt, a British author whose historical crime novel, Treachery, was published in February, presents a compelling case for treating ISIL killers as simple murderers.

She cites 16th century attempts by Queen Elizabeth I to defeat Catholic subversion by prosecuting men who had travelled abroad to train as priests for treasonous disloyalty, not as heretics whose crime was their faith.

“Nobody was fooled,” Merritt wrote in The Observer newspaper. “The priests became martyrs and, far from deterring would-be missionaries, their deaths only inspired more.”

In other words, Mr Hammond and his fellow ministers need to tread carefully to avoid, as Merritt puts it, granting “the terrorists a grandeur that serves their own view of their ‘mission’”.

Acute though the risk may be, there remains an argument for wielding the stick provided it is accompanied by a compensating carrot.

In the short term, Britain and other countries facing the defection of their own citizens to a hostile cause should heed respectable voices advocating leniency for returning recruits whose disillusion, and willingness to deter others, can be ascertained. No one can be sure how many there are. But authoritative observers suggest dozens of Britons are already desperately seeking a way out. It is foolish and self-defeating, they say, to block all exits from the mess, admittedly self-created, for those who see the light before committing any of the crimes against humanity ISIL considers legitimate.

But there must also be a longer-term objective, its sincerity underpinned by immediate preparatory action. Few serious observers doubt that manipulative and often highly intelligent recruiters succeed to some extent because young Muslims, from petty criminals to academically high-achieving students, feel alienated by discrimination and disadvantage within western society. Only that society can address this grievance.

In Britain, as in France and other countries with sizeable Muslim communities, there is an unanswerable need for a strong, plausible plan of action to eliminate prejudice, in so far as it influences employment, policing, education and housing. Since this will cause offence to some middle-class opinion, mainstream political parties may therefore have a duty to forge some form of unified approach.

Little can be achieved overnight, which makes it imperative that a start is made soon – before the opportunists of the far right make further advances that would leave the mission so much harder to accomplish.

There are already signs of limited success in persuading Muslims to turn to the authorities with concerns about suspicious activities by their relatives and friends.

If only they can be shown that purposeful strides are being made towards social equality, they may also become willing to accept that exemplary punishment is warranted if disaffection passes from dissent to betrayal.

Colin Randall is a former executive editor of The National