Few will disagree that the Middle East has had a brutal and bruising year. The positive things about life, love and work in the region have too often been overshadowed by the darker sides of life.

Next year, however, could be the year that the region turns an important corner – or, rather, more than one.

In Syria, the international community is finally inching towards some form of resolution. The combination of Russia's entry into the civil war, the spillover from the refugee crisis into Europe and attacks by ISIL in western cities has focused the minds of US and European leaders.

Since the beginning of the Syrian civil war, Middle East observers have argued that a war of Syria's magnitude cannot be contained. Only now has the message been heard in western capitals. A solution, then, is likely, or at least some form of stalemate.

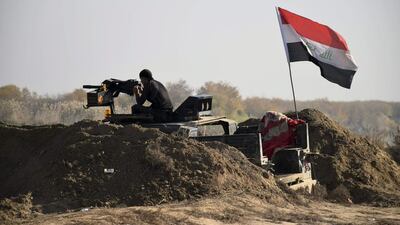

This will be the year that Iraq retakes the majority of its territory from ISIL. I expect Mosul will be retaken in the next few months. (ISIL's other big city, Raqqa, may take a bit longer.)

The same will happen in 2016 in Yemen, where the Houthis will finally leave Sanaa. How they leave – through negotiation or via the force of the Saudi-led coalition – is yet to be seen.

But simply retaking territory doesn't mean knowing what to do with it.

In all three countries, even if most parts are returned to the control of the central government, the underlying issues will remain.

In Iraq, the question of how the different communities live together and equitably share resources has not been settled for decades. It was not settled under Saddam Hussein and it has not been adequately answered under any of the recent governments.

What has happened instead since the fall of Saddam has been an attempt at a power grab by the previously marginalised Shia Iraqis.

The formerly mixed cities of Baghdad and Basra have been cleansed, overturning centuries of communal living and intermarriage between Sunni and Shia.

Reversing that will take years of confidence bulding – and a belief among both communities that the central government can guarantee their safety.

No wonder, then, that a belief has grown up among some Kurds, Sunnis and Shia that the state is doomed to fragment and the only solution is separate statelets.

In Yemen, something similar is going on. The sandwiching together of north and south Yemen, two regions with very different histories, into one nation in the 1990s, compounded by autocratic rule, corruption and the funelling of resources into the hands of a few, brought about the conditions for the revolution.

Even after a government is restored in Sanaa, how – and indeed if – the two regions can live together will still need answering.

The most dangerous of all three will be Syria.

If the international community cobbles together a plan that is acceptable to the Assad regime, that plan is extremely unlikely to be to the liking of most of those Syrians who supported the revolution.

From this vantage point, two things appear unlikely: that Bashar Al Assad will step down, and that all the Syrian rebel groups will accept him remaining.

That, then, is a recipe for more conflict, even if at a lower level than now.

The underlying question of the past few decades remains. Can a repressive regime ruled by a minority adequately reflect the aspirations of the Sunni majority?

If the answer to that question is no – and the civil war appears to be a clear demonstration of that answer – then something in that equation must change, or conflict will continue.

This coming year, then, will be the year that major cities in Iraq, Syria and Yemen are brought back under central government. If only that were the end of the story. The really complex part is what happens after.

falyafai@thenational.ae

On Twitter: @FaisalAlYafai