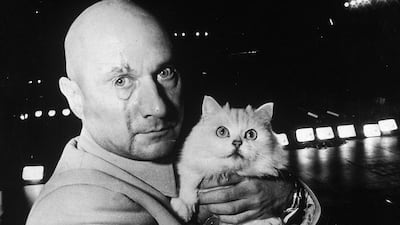

For most of the early James Bond films, the villain was almost always the shadowy and sinister Blofeld, a character rarely seen in full and mostly depicted as a pair of expensively-manicured fingers stroking some kind of exotic cat.

“Leaving so soon, Mr Bond?” Blofeld would purr in his languidly evil English accent, as James Bond attempted some high-wire-act escape. “I’m afraid I must insist that you stay.”

Blofeld spoke in an English accent, of course, because as everyone knows the very best villains sound like etiolated British aristocrats, but he wasn’t supposed to be an actual British citizen. Blofeld was an international evildoer of unspecified national origin. Even his name was impossible to locate on an ethnic map. “Blofeld” sounds neither too German nor too French, and ends up almost Swiss in its neutrality.

The author of the James Bond series of novels, Ian Fleming, and the subsequent writers and producers of the smash-hit series of James Bond films, clearly wanted Blofeld to represent a multinational and multi-ethnic kind of nastiness.

James Bond burst onto the cinema screens during the coldest and most dangerous years of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union, and yet the intrigue underlying most of the movies involved Blofeld and his evil gang – called Spectre – attempting to set these two paranoid and over-armed nations against each other.

That turned out to be prudent. The James Bond films have remained fun and exciting for almost 50 years, in no small measure because they never took sides in what was, after all, a grubby political conflict.

Watching You Only Live Twice on late-night television recently was blissful and mindless fun. You didn’t have to put any of it into the context of the time, in which a bitter proxy war was raging in South East Asia, nuclear weapons were piling up in Eastern and Western Europe and the world seemed perpetually on the brink of extinction. It wasn’t about geopolitics, it was about an evil mastermind with a piranha-filled pool and a dashing secret agent with a tiny helicopter and a way with the ladies.

Today, though, action and adventure pictures seem at a loss to depict truly scary – and lasting – villains. In the latter-day Bond films, the bad guys seem chosen from among a very small collection of international businessmen.

Gone are the cats wearing diamond collars and legions of minions in orange jumpsuits. In many of the recent pictures, the evil brain behind the nefarious events is some kind of media baron or fossil fuel tycoon, neither of which is a particularly stylish choice. I’ve met a fair number of media barons and fossil fuel zillionaires, and it’s safe to say that I’ve never been struck by their menacing charisma.

Most of them, in my experience, are just colourless dudes trying to get through next quarter’s earnings reports without being crucified in the financial press. Blofeld, it must be said, never seemed troubled by activist shareholders or inflexible debt holders.

For a few years, many action adventure movies relied on the lazy (and vaguely racist) choice of depicting the villain as either a Japanese, or more recently Chinese, industrialist. In the 1980s, when American and European moviegoers were coming to grips with the emerging Japanese economic superpower, there were a lot of movie bad guys with Japanese surnames.

Later, as China rose to prominence, filmmakers chose them to carry the bad-guy mantle. Now that Chinese investors have taken large stakes in American film studios and movie companies, it’s hard to find a Chinese villain in any big-budget action picture. If there’s one ironclad rule to movie financing, it’s this: do not insult your biggest investors.

That leaves the Russians, who now serve as a catch-all default setting for any movie villain, murderous psychopath or pitiless criminal tycoon. Russian bad guys with thick, swollen-tongue accents are now the cliché choice for writers and directors of action pictures.

When you want to convey to your audience as efficiently as possible that the bad guy in your story is really, really bad and also really, really rich, the quickest way to do that is to give him a fuzzy Russian cap and a henchman named Ivan or Pyotr.

The problem, as we’ve all experienced, is that there really are a lot of very rich (and very loud) Russian billionaires all over the place – swanning around hotel resort pools in swanky locations, unspooling large amounts of cash from fist-sized rolls, wearing hilarious outfits in sedate three-star restaurants – so that the film versions seem comparatively tame and unspecial. Even the current leader of the Russian Federation seems more outlandishly villainous than his movie bad-guy counterparts, and that’s never a good sign.

Evil masterminds in movies are supposed to be more menacing and over-the-top than their real-life models, not less. It makes one long for the days of Blofeld and his bejewelled cat, a villain without a country.

Rob Long is a writer and producer in Hollywood

On Twitter: @rcbl