In early 2014, while reporting on a particularly savage wave of car bombings in Iraq, I asked a British general if he had heard of a terrorist with the nom de guerre of Abu Bakr Al Baghdadi.

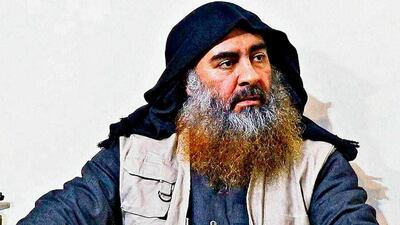

Then little known to the wider world, Al Baghdadi was already building a reputation as a fearsome operator. Yet other than a prison mugshot and a string of other aliases such as “the Ghost” and “the Invisible Sheikh”, he was an enigma.

"We either arrested or killed a man of that name about half a dozen times. He is like a wraith who keeps reappearing and I am not sure where fact and fiction meet,” the general told me. “There are those who promote the idea that this man is invincible, when it may actually be several people using the same nom de guerre.”

Six months later, the man in that prison mugshot became renowned the world over when he climbed the pulpit of Mosul's Al Nuri Grand Mosque and declared himself leader of the new "caliphate" carved out of Iraq and Syria by his ISIS forces. That the military's best minds had previously wondered if he even existed was perhaps the ultimate proof of his ability to disappear into the shadows as an insurgent.

Yet until last week, when US forces finally killed Al Baghdadi at a hideout in north-east Syria, both man and myth had combined to create arguably the most brutal terrorist machine ever seen on the planet.

In Syria and Iraq, his fanatics slaughtered fellow Muslims, raped and enslaved Yazidis, and forced millions to adopt a warped interpretation of eighth-century Islam. Further afield, his propaganda about life in the so-called caliphate drew tens of thousands of foreign followers, including the "Beatles", the British militants who kidnapped and murdered western aid workers and journalists in Syria.

Meanwhile, ISIS cells and lone wolves spread terror, death and destruction on nearly every continent, from Easter Day bombings in Sri Lanka to knife rampages on London Bridge.

Earlier this week the parents one of those murdered aid workers, Kayla Mueller, welcomed Al Baghdadi’s demise, although there seemed little chance of it bringing closure for their daughter's death. Mueller, who was taken hostage by ISIS and repeatedly raped by Al Baghdadi, died in a coalition airstrike in 2015 but her body has never been found.

In similar fashion, hopes that Al Baghdadi's death will draw a line under his death cult seem equally improbable. He had always known that a drone strike could kill him at any minute and had decentralised the organisation of ISIS so that it could function without him or any other commander-in-chief.

Like Al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden, he refused to communicate by mobile phone or any other trackable device, cutting himself off from day-to-day operations. While US officials are using material gathered at his hideout to pursue other ISIS commanders – a day after his capture, a second airstrike killed ISIS spokesman Abu Hassan Al Muhajir – they are unlikely to have uncovered an intelligence “treasure trove”.

Nonetheless, the man tipped as ISIS's next leader – Abdullah Qardash, a former Baathist army officer, who spent time with Al Baghdadi in a US-run jail in Iraq – will find him a hard act to live up to.

So what was it that made him so capable? After all, when Al Baghdadi took over ISIS's predecessor organisation in 2010, Al Qaeda in Iraq, it was in disarray, decimated by coalition operations and disenfranchised by the Sunni Awakening in Iraq, in which tribal leaders who had formerly fought the US aligned themselves with their former foes to battle the likes of Al Qaeda.

One advantage, says Michael Knights, of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, was Al Baghdadi’s background. As an Iraqi-born Islamic scholar, he had good standing in both of the key insurgent networks that fused to form ISIS – the Iraqi nationalists, drawn mainly from the security wings of Saddam Hussein's Baath regime, and the hardline jihadists. That gave him more appeal than predecessors like Abu Musab Al Zarqawi, a Jordanian-born ex-convict.

Before Al Baghdadi, the leaders of Al Qaeda in Iraq tended to be either foreigners or “low-brow guys” such as Al Zarqawi, whereas the ISIS leader had religious training and was known locally, according to Dr Knights. He also had strong organisational skills but was content to delegate authority – one of the reasons why he lasted.

An early example of that organisational prowess was in 2013, when his followers staged a mass jail break from Baghdad’s Abu Ghraib prison, springing 500 fellow extremists from one of the most heavily guarded prisons on the planet. He could pull these jobs off because half his lieutenants were former Baathist intelligence officers, who knew Iraq well.

Lacking Bin Laden's charisma or Al Zarqawi's ego, he avoided videotaped addresses glorifying his success. That, though, merely fuelled the mystique and aura surrounding him. While Bin Laden, preaching from remote caves, looked like a faded, reclusive rock star, Al Baghdadi came across as a frontline soldier, a man of deeds, not words. Comrades spoke warmly of a leader who was not afraid to show up on the frontlines, yet also cared for their welfare, particularly as he was said to veto operations that carried too much risk.

As head of the so-called caliphate, Al Baghdadi left that caution behind him. Had he not sanctioned the public beheadings of US hostages, for example, America might never have launched all-out war against him and his domain might well remain today. The real question now, though, is whether he will continue to inspire people from beyond the grave.

Although the UN estimates that up to 30,000 foreign ISIS fighters are still alive, the physical existence of the ISIS caliphate itself was for many the key attraction, offering everything from security and brethrenship to marriage and martyrdom.

With that now gone, many of the misfits and malcontents who were drawn to ISIS will lose interest: as natural bandwagon-jumpers, few will want to die for a cause that is no longer a winning team. Thousands of ISIS's western volunteers have already returned home over the last three years. Had even a few heeded Al Baghdadi's call to carry out lone-wolf strikes, America and Europe would have witnessed far more terrorist attacks.

For the hardcore, ISIS offers other combat theatres to head to, but none where it has turf of its own. In Libya, it lost its stronghold in Sirte two years ago. In Afghanistan, it is overshadowed by the rival Taliban. In Sinai province, it is restricted to hit-and-runs on the Egyptian army. In Nigeria, Boko Haram has pledged loyalty but shows more interest in local grievances than ISIS's trans-national agenda. Nor, for the average European extremist, are these theatres as easy to reach as the old caliphate, whose western border was accessible via visa-free travel to eastern Turkey.

Instead, many think ISIS's best chances lie in a comeback in the very place where Al Baghdadi first formed it – the blood-soaked Sunni heartlands of western and northern Iraq. Its fighters may be long gone from cities like Mosul but the grievances that first gave them footholds there remain.

Two years on from Mosul's liberation, 300,000 residents are still homeless. Far from helping the UN-led reconstruction effort, local politicians stand accused of blocking projects that do not generate kickbacks. Iraq teeters on a precipice once again. At least 250 civilians have been killed this month during mass protests against government failures and hundreds more have been injured. Economic hardship and corruption are threatening to tip the country into instability once again. Across the region, pro-Iranian Shiite militias such as the Popular Mobilisation Forces, who helped in the battle against ISIS, have begun fanning sectarian tensions and have even been implicated in some of the recent deaths.

Already, ISIS cells are reforming, mounting guerrilla attacks, denouncing the government and demanding protection money, just as they did before seizing Mosul in 2014. The contest to win the hearts and minds of one of Iraq's most abused, neglected and volatile constituencies is back on.

Few, though, think ISIS's flag could fly here again soon. Robert Tollast, a former adviser to Iraq's foreign affairs ministry, says the terrorist group stands little chance of regrouping in the near future. It is intensely disliked by local tribal leadership and there has been harsh collective punishment of communities suspected of colluding with them, which the government has not acted on. "That is a human rights violation that feeds tribal rivalry, but it shows how much support they have lost," he says.

Still, similar things were said about ISIS's predecessor, Al Qaeda in Iraq, which likewise alienated people with its brutality. Dr Knights agrees that short-term, ISIS is finished, but fears it could re-seed among those youngsters whose parents were followers. Tens of thousands of ISIS "cubs" now languish in vast refugee-cum-prison camps like Al Hol in Kurdish north-east Syria, where local guards can barely control the inmates. They have warned that US President Donald Trump's recent decision to pull troops from the region will make that task all but impossible.

Indeed, even if the camps were properly secured, the challenge of re-integrating so many traumatised, radicalised children and teenagers from Al Hol and elsewhere is a daunting one. Al Baghdadi might be gone but the problem of stopping his cubs growing into wolves is likely to remain for decades to come.

Colin Freeman is a journalist and author of The Curse of the Al-Dulaimi Hotel: And Other Half-truths from Baghdad