The Financial Action Task Force, perhaps one of the world's least-known but most influential international organisations, concluded its tri-annual conference in Paris on Friday. The FATF's mission of enhancing global banking standards to tackle threats from trafficking to terrorism is typically regarded as "technical" – that is, too dull for politics – even though its findings have the power to cripple entire nations' ability to do normal business.

Little media or diplomatic attention was paid to its "blacklist"; the drama was reserved for Pakistan, to the exclusion of the other 17 countries currently on the FATF "grey list". Then again, few other countries are as precariously posed on the knife-edge of global acceptance as Pakistan. So how did the FATF emerge as a crucial battleground for the country, and what does its most recent decision mean?

The FATF’s creation dates back to 1989 and the internationalisation of the US "War on Drugs". American experience had shown that countering money-laundering was the key to containing the influence and power of organised crime, but that the cross-border nature of drug cartels also required long-term international co-operation.

This was a matter on which powerful governments across the world agreed in principle, and were keen to demonstrate action, regardless of any reservations they held over American power. A similar dynamic played out post 9/11 when the FATF’s mission expanded to curbing terrorist financing and WMD proliferation. Simultaneously, the FATF saw a major expansion to include the world’s new financial powerhouses, including China in 2006 and India in 2010.

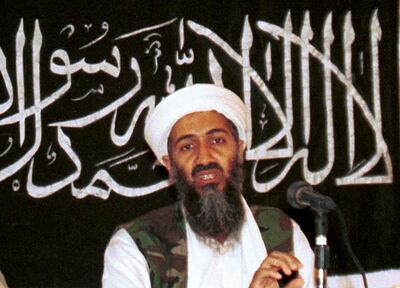

During Barack Obama's tenure as US president, the FATF's targets evolved beyond non-state actors such as Al Qaeda and the Sinaloa Cartel in Mexico to include governments such as Iran and North Korea, whose insurgent financing and missile trafficking were regarded as threats to the international system. The FATF also evolved beyond merely "naming and shaming" countries that failed to live up to standards.

What emerged was a system for quarantining blacklisted countries from the international financial system, and a grey list of candidates for blacklisting. Most governments have budget deficits, which are financed through international bond markets and borrowing; this becomes almost impossible for blacklisted states. The results for trade and investment are just as devastating, given that FATF-compliant banks' caution over transacting with blacklisted jurisdictions.

The international community’s co-operation with these peculiarly American priorities was driven by a mix of pragmatic considerations. On one hand, the intransigence of Iran and North Korea had alienated many neutral or even sympathetic governments. On the other, the threat of exclusion from the US financial system for violating sanctions was simply too much to risk. Just as convincing was the Obama administration’s offer of financial access denial as an alternative to military action. Given the disastrous cascading results of the Iraq war, there was universal agreement that actual war between America and its enemies risked global stability; almost anything else was preferable. For all its differences with its predecessor, the administration of Donald Trump has continued to favour such financial weapons over bombs and boots.

The other area of continuity for Washington and the international community has been a growing frustration over the Pakistan Army's alleged links to extremist groups. The Pakistani government routinely denies all such charges to the enduring frustration of the US and other members of the international community, who have now faced persistent threats of violent religious extremism for a generation.

By the end of George W Bush's tenure as president, the US was engaged in unilateral military action on Pakistani soil. These programmes peaked in the Obama era but have been too destabilising to sustain. Meanwhile, cuts in military aid under the Obama and Trump administrations only reduced Washington’s influence over the most powerful pro-American element in the country. The changes in Pakistani policy obtained at high cost remained skin deep; many banned groups resumed open fundraising and organising under new names, and their leaders rarely remained imprisoned for long.

Pakistan’s placement on the FATF grey list in June 2018 came with international consensus on the need to break the pattern of superficial reform. The civilian government promptly committed to a 27-point, 15-month reform package intended to amend and enforce a regulatory framework to suppress terrorist financing and organising. Pakistan’s military brass, meanwhile, treated this in the usual fashion, that is, as a perception-management problem to be finessed through tacit understandings with foreign allies and a big public relations campaign. It did not work this time.

When Pakistan faced review in October 2019 with only five out of its 27 objectives completed, the short extension came with greater pressure to demonstrate its commitment. The FATF, in reviewing the most recent assessment, acknowledges Pakistan's progress – now up to 14 – but has warned that failure to fully comply by the next meeting in June 2020 will result in Pakistan's blacklisting. Crucially, Pakistani government finances are particularly dependent on international lending. FATF blacklisting would very likely produce an economic catastrophe and serious political unrest.

All this occurred despite Chinese leadership of the FATF since July 2019, and vital Pakistani support to US negotiations with the Taliban. Although the Chinese government has offered many soothing public words to Pakistan, its consistent support for the FATF at a time of serious differences with the US underlies a larger truth. Pakistan's performance in eliminating terrorist infrastructure remains in the grey zone, but the broader international community continues to see the importance of lasting change in black and white terms.

Johann Chacko is a writer and South Asia analyst