Recent construction work at the site of the Sheikh Khalifa mosque at Awd Al Tawbah in Al Ain has brought to attention a remarkable archaeological discovery. Archaeologists from the Department of Culture and Tourism – Abu Dhabi have discovered the oldest known mosque in the UAE.

Pottery found in and around the mosque tells us that the Awd Al Tawbah mosque belongs to the early Islamic period, which stretched from the seventh to 10th century AD. This period witnessed great Arab conquests and the rise of an Islamic empire – the caliphate – which stretched from southern France to western China. A new capital was built in Baghdad in the mid-eighth century and quickly grew to be one of the largest cities in the world. Science and the arts flourished in a tolerant and cosmopolitan society, which made Islamic civilisation the wonder of the world.

It is important to understand that the mosque is not an isolated monument. Its full significance can only be understood by placing it into a range of interpretative contexts. The view from the mosque takes in a series of widening horizons – the local, the regional and the international – which allows us to situate it in the golden age of Islamic civilisation.

Archaeological discoveries like this make an important contribution to the national history. At the same time, they serve to anchor the Emirates in the greater flow of human history.

The mosque is part of the larger archaeological site of Awd Al Tawbah, itself part of the historic landscape of Al Ain and neighbouring Buraimi, which together constitute the near horizon.

The early Islamic period in Al Ain is one of four major episodes of intensive occupational activity, the others being the Early Bronze Age, the Iron Age and the late Islamic period. This depth of human occupation and antiquity of the historic landscape is one of the reasons why the oases of Al Ain were inscribed on the Unesco list of world heritage sites in 2011.

The remarkably well-preserved remains of an early Islamic village were found in Buraimi, on the Omani side of the oases. Geophysical survey next to the border fence revealed a network of mud brick field boundary walls and underground aqueducts – the famous falaj irrigation system – running from Oman into the Emirates.

One of these disused aflaj detected by ground-penetrating radar ran parallel to the present-day Jimi falaj and was picked up in an archaeological excavation at the proposed site of a school next to Jimi Oasis. More field boundary walls and aflaj were found around the Awd Al Tawbah mosque. Whether the early Islamic landscape constituted a series of individual oases or a large single oasis remains an ongoing research objective for archaeologists.

Almost every archaeological test pit dug in and around the oases by DCT – Abu Dhabi produces a handful of early Islamic pot shards. The evidence suggests that the oases expanded significantly in this period. The Palestinian geographer Muhammad Al Muqaddasi, writing in 985AD shortly before the Awd Al Tawbah mosque was abandoned, describes the landscape of Al Ain as “abounding in palms”.

This thriving oasis settlement was known as Tuam Al Jaww, "Tuam of the plain" to historians. It was the power base of the Banu Sama ibn Luayy ibn Ghalib, a branch of Quraysh, the same tribe as the Prophet Mohammed.

The Banu Sama played a key role in assisting the Abbasid Caliphate in Iraq to defeat the Ibadi Imamate of Oman in 898AD. Al Muqaddasi called these ancient Emiratis “men of fortitude and forcefulness”. This event marks the emergence of the emirates as a distinct political entity and established Sunni Islam as the dominant religious sect.

Shifting our gaze to the middle horizon takes in the national and regional setting. Awd Al Tawbah is one of many early Islamic sites in the Emirates and its neighbours, reflecting the booming regional economy under the Abbasid caliphate of Baghdad.

A settlement of arish, or palm frond houses, surrounding a souq, caravanserai and palace has been found in Jumeirah in Dubai. The palace resembles the country estates of the Umayyad and Abbasid caliphs in Syria and Iraq. It was beautifully decorated with carved stucco panels like the slightly earlier monastery of Sir Bani Yas in Abu Dhabi.

The Jumeirah site was probably also part of the ancient emirate of Tuam. Its fame was such that the 11th century geographer Abu Ubayd Al Bakri, writing in the libraries of Cordoba in Islamic Spain, and the 13th century Yaqut Al Hamawi, using the libraries of the Seljuk Turks in the Silk Road city of Merv, both wrote of this not so obscure corner of the Islamic world.

Their testimony makes it clear that Tuam was the early Islamic pearling capital of the Gulf. It gave its name not just to a type of pearl but to the waters of the Gulf itself. Remarkably, Al Bakri writes not of the Arabian Gulf but of the Tuamian Sea. This is one of the earliest references to the Emirati pearling industry in the Islamic period.

That the sites of Jumeirah and Awd Al Tawbah should constitute the maritime and terrestrial elements of a single emirate is nothing to be wondered at. The Arabic name Tuam, meaning "twins", itself hints at the duality of settlement. Survival in so marginal an environment has always necessitated the human exploitation of every available ecological niche. The memory of the tahwil, or annual migration from the coast to the oases, is still alive among an older generation of Emiratis.

The other major early Islamic settlement of the Emirates was Julfar, the ancestor of the modern city of Ras Al Khaimah. Archaeological evidence for Julfar in this period has been found at the mound of Kush and island of Hulaylah. Extensive remains of arish houses suggest that the settlement was quite large. It was here, at the outset of the early Islamic period, that the men of Abd Al Qays, Tamim and Azd assembled to join in the Arab conquest of Iran.

Among the warriors who fought in the campaign was Al Muhallab ibn Abi Sufra from Dibba. The town of Dibba is today split between the emirates of Fujairah and Sharjah and the Sultanate of Oman. He subsequently rose to prominence in the Muslim conquest of Khurasan in Central Asia and Sindh in modern Pakistan. His descendants ruled these provinces, together with the territories of the present-day UAE and Oman, on behalf of the Umayyad caliphate in the first half of the eighth century.

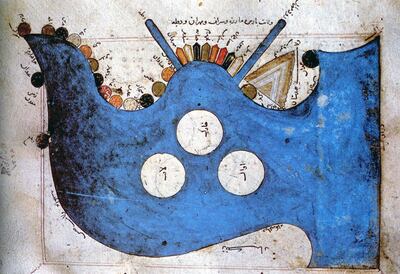

This leads us now to lift our gaze to the far horizon, where we come to consider the international context for the Awd Al Tawbah mosque. The early Islamic sites of the Emirates were all connected to regional maritime hubs – particularly Siraf in Iran and Sohar in Oman – through which they gained access to the world at large. Imported pottery found in and around the mosque and at other contemporary sites allows us to reconstruct the trade connections of the early Islamic Emirates.

Easy access to Siraf and Sohar gave its population a window onto the Indian Ocean. Trade boomed in this period. “This is the Tigris,” the caliph Abu Jafar Abdallah ibn Muhammad Al Mansur is reported to have said when he established Baghdad. “There is no obstacle between us and China: everything on the sea can come to us on it.” These words echo in the archaeological record of the early Islamic Emirates. Chinese imports include Changsha, Dusun and Yue stonewares made during the Tang and Song dynasties.

Many different types of Indian ceramics are found in early Islamic archaeological sites in the Emirates. The Arab historians refer to Indian peoples such as the Zutt and Sababijah living in Khatt, an important oasis behind Julfar in modern Ras Al Khaimah. The Christian Arabs who worshipped in the monastery of Sir Bani Yas in Abu Dhabi, moreover, shared their Syriac liturgy with the St Thomas Christians of Kerala. These historical reflections remind us, as one scholar famously put it, that "the archaeologist is digging up, not things, but people".

East African imports include Dembeni earthenwares from the Comoros Islands and so-called "plain wares" in the Tana tradition from Kilwa. The quantity of East African ceramic imports in Al Ain is greater than those of India and China combined. This unexpected discovery prompted a Zayed University research project to explore historic links between the Emirates and Zanzibar.

The Indian Ocean world is brilliantly evoked by the Accounts of China and India of the nukhadah (ship captain) Abu Zayd Al Sirafi written in the 920s AD. The book has recently been translated and published by New York University Abu Dhabi. Al Sirafi tells us that 120,000 Muslims, Jews, Christians and Zoroastrians lived in China at the peak of the Abbasid Indian Ocean trade in the ninth century: a powerful statement both to the globalisation and tolerance of the age.

Emirati sites like Awd Al Tawbah, Jumeirah and Kush were undoubtedly provincial by comparison with Baghdad, Damascus or Cairo. Yet as Al Muqaddasi reminds us: “Although the towns of the Arabian Peninsula are small, they have the full reputation of towns.” Provincial they may have been but isolated they were not. The Emirates can be shown to have fully participated in and actively contributed to the golden age of Islam.

Dr Timothy Power is an archaeologist and historian focusing on Arabia and the Islamic world and an associate professor at Zayed University in Abu Dhabi. His book A History of the Emirati People is due to be published in 2020