The whole world is watching with horror and trepidation the unfolding of the coronavirus pandemic in the US. The country that played such a key role in supporting nations buckling under the Ebola epidemic six years ago, and before that did more than any other to support the fight against Aids in Africa, has now suffered more than 2.6 million Covid-19 infections and more than 129,000 deaths.

The crisis does not seem to be abating either, with new waves sending infection rates soaring – the opposite of the "flatten the curve" mantra that we all internalised at the beginning of the pandemic – and arresting reopening plans. Up here in Canada, things appear to be moving at long last in the right direction, but the turmoil in the US feels too close for comfort.

There are many apparent reasons for the intensification of the crisis in the US, from uneven lockdown strategies to inexplicable defiance of urgent public health measures in some states by those in power, as well as conflicting messaging on some of these measures and the need for them. Instead of leading by example, President Donald Trump appeared in a campaign rally in Oklahoma, right around the time coronavirus cases were spiking in the state.

Mr Trump's predicament is one that has been mirrored in other countries governed by nationalist leaders who rode the wave of right-wing populism in 2015 and 2016 in the immediate aftermath of the European refugee crisis. The top five countries in terms of sheer number of confirmed cases are America, Brazil, Russia, India and the UK, who are all headed by beneficiaries or backers of the right-wing surge. Some of these leaders, including Mr Trump, Jair Bolsonaro and Boris Johnson (at least at the start of the pandemic), made a point of downplaying the public health risks and played politics with the lives of their citizens.

The result has been hundreds of thousands of avoidable deaths. Propelled to power by appealing to fear and division, and scornful of experts, they failed at a critical, historic moment. The bankruptcy of their paradigm and worldview was ironically revealed just when a different kind of fear took hold over their populace – the fear of a virus, not the other.

The poor handling of the pandemic has led in the latest round of polls to an apparent decline in the popularity of right-wing parties, with concerns over the public health response eclipsing the anti-immigration sentiment that has receded in the minds of voters over the past few months.

It is difficult to see the silver lining in a global crisis that has led to so much death and suffering. But I do confess that in the first couple of months, amid the generosity and social solidarity I saw on social media and in Montreal, where I live, I was filled with some hope.

There was hope that we might emerge out of the pandemic with a renewed sense of social cohesion, greater empathy towards the most vulnerable, a stronger understanding of the value of family ties and friendship, deeper solidarity in the face of existential crises such as climate change, and a feeling that we are in it together, that the polarisation that characterises politics and social media will retreat. After all, if you need to quarantine or get food to your elderly parents, it does not matter if the neighbour who will take care of it is a liberal or conservative, black, brown or white.

Ca va bien aller, right? Everything will be alright.

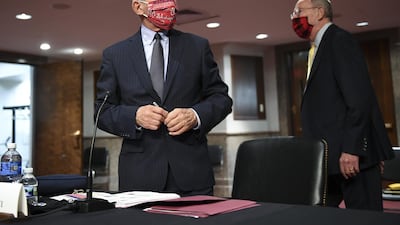

Looking at the US, it is bewildering to see how a public health intervention as basic as wearing a mask has become a sign of political allegiance. Not that everybody in Montreal wears a mask – I would say perhaps one or two in 10 wear it in my neighborhood on my walks, and I do not really wear it except in close quarters like grocery stores. But at least it is not, as far as I have seen, perceived as a political statement.

Part of this is the fault of political and public health leaders. Mr Trump of course does not wear a mask and has promoted questionable treatment options, but officials in charge of the health response in Canada and the US have vacillated on the issue of masks despite the evidence pointing that they save lives. This was because early on there was a shortage in protective equipment for healthcare workers – a logical calculation, but one that cost lives and undermined more recent advice recommending and sometimes requiring people to wear them.

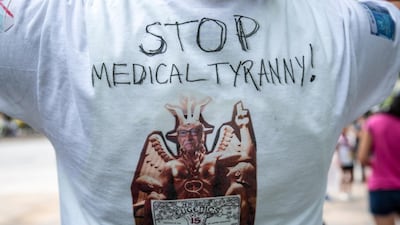

But some of it is personal choice. Viral videos have circulated through social media in recent days showing angry shoppers denouncing employees at shops and grocery stores where masks are required, sometimes proclaiming a defiant political allegiance to Mr Trump or his party.

Have we become so polarised and angry that a simple and effective public health measure has become a litmus test of loyalty to a political leader? Have we become so fragile that any change in the status quo of consumerist culture is cause for panic and denial? Have we become so fragmented that protecting other people from a deadly virus is a political issue?

Ca va bien aller? I am not so sure anymore.

Kareem Shaheen is a former Middle East correspondent based in Canada