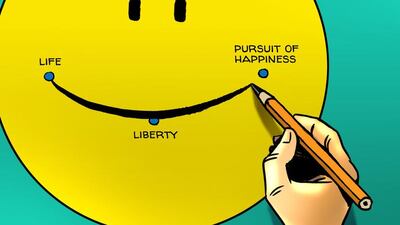

The most famous statement about happiness in the United States was occasioned, happily, by its birthday, July 4, 1776: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness.”

The Declaration of Independence then proceeds to explain the need for a government to secure these rights, and provides various hints about the proper institutional arrangements to do so. But no elaboration of the “Pursuit of Happiness” can be found there. The Constitution framed years later, in 1787, to effect the Declaration’s principles, does not mention happiness, though perhaps its announced purpose “to secure the Blessings of Liberty for ourselves and our posterity” subsumes happiness as a goal.

_____

This article is part of our supplement on happiness, which unites us all. For more happiness stories visit our dedicated page.

_____

Thomas Jefferson, primary author of the Declaration, freely admitted that he had not sought originality. The Declaration, he later claimed, was meant to convey the common sense of “the American mind”. But the mind most clearly dominant in the Declaration is that of an Englishman – the philosopher John Locke. Locke had taught that the basic purpose of government was to provide individuals protection for essential interests that he, following his countryman Thomas Hobbes, dubbed “rights”. Locke formulated these rights as a trilogy of “life, liberty, and estate,” together conceived as the “property” of every person. Rights are the things we humans really, seriously want: to live, to be free, and to attain some possessions to comfort our days on earth.

Jefferson replaced Locke’s “estate” with “Pursuit of Happiness”. Perhaps he did not want to taint the poetic Declaration with mention of prosaic material concerns. But this seems unlikely given the inclusion of commercial and fiscal grievances in the long catalogue of specific complaints that follows (appropriation of land, curtailment of trade, and taxation without consent). Or perhaps he meant to suggest that personal happiness requires more than wealth. Health, family, friends, knowledge and reputation easily spring to mind as other ingredients of happiness. What is undeniable, though, is that the fundamental American statement on happiness affirms only its pursuit as a matter of personal right. Some questions immediately arise.

First, is the pursuit of happiness itself happy? The very grammar of the phrase seems to deny this. Locke himself had taken pains to hint that acquisition of property usually involves labour that is unpleasant. Not many people happily anticipate returning to work after the weekend. If this is true, American life seems to promise a long, laborious chase for something that, like an imagined oasis in the desert, continually recedes from our striving. As a palliative for our efforts, Locke invites us to contemplate the penury of a “king of the Indians” relative to the income of a hard-working “day labourer in England”. But won’t the worker’s thoughts more likely be directed toward the old school chum now managing the hedge fund? The pursuit of happiness just may not deliver on its promise. It was, after all, a British band steeped in American blues that famously proclaimed, despite multiple attempts, its failure to obtain any satisfaction.

Second, what consequence follows from a personal right to pursue happiness? Rights, as you recall, are property. Our immediate thought might be that we can do with our property, or choose what pursuit, we wish, but no human community could survive such absolute personal freedom. At a minimum, we can see that no person seeking happiness should be allowed to deprive another person of the equivalent right, given that “all men are created equal”. So I can pursue my idea of happiness only if the community legitimises my idea of happiness as something that can be safely pursued. If I disagree with the community’s limit, then equality of right dictates that everyone else can disagree, so we will never have an order sufficient to make my pursuit secure. The community thus cribs and confines happiness within allowable limits, which may leave me profoundly unhappy, since this right is said to be something inseparable – unalienable – from myself.

Next, doesn’t my personal right to pursue happiness beget another reason for unhappiness? Locke, again following Hobbes, thought that the necessary curbs on happiness’s pursuit would only prove effective when everyone reflected on their absence. This is the famous teaching of the “state of nature.” Equal natural liberty means freedom to judge for oneself what one requires for life and happiness. This freedom to judge encompasses liberty to act on one’s judgement, even so far as the right to kill anyone deemed a threat to life and happiness. The miasma of violent death thus pervades the natural human state. Hobbes and Locke are counting on the fear of untimely death to compel us to accept the bonds of civil society. The “stick” of death and the “carrot” of happiness channel the strongest human passions in the proper direction. But doesn’t mortal anxiety, however useful, inevitably corrode the possibility of happiness? As yet another Englishman, Edmund Burke, later complained of the modern, liberal ideas: “At the end of all their vistas, you see nothing but the gallows”.

This sombre talk of death brings me to the final point. Chasing the idea of “the pursuit of happiness” has led to the conclusion that someone freed from fear of death, unfettered by concerns of costs to others, liberated from painful drudgery of the daily grind, may actually come close to a real feeling of happiness. Egoistic, irresponsible ignorance as bliss? Perhaps, Mr Jefferson, we should pursue something else – so that happiness will find us.

Roger McDonald teaches political science at John Jay College at the City University of New York, explains