The UN will mark its 80th anniversary in London on Saturday, as scepticism over the organisation’s global role is growing around the globe.

The UK played a foundational role in setting up the UN, and the day-long conference will take place in Central Westminster Hall, where delegates held the first General Assembly in 1946.

Syrian pilot Maya Ghazal, the UN Refugee Agency's goodwill ambassador, will address the conference, as will Annalena Baerbock, the president of the General Assembly.

Departing UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres will attend a multi-denominational service led by the Central Halls’ Methodist Church in the morning. Ms Baerbock, physicist and musician Brian Cox and former Nato secretary general George Robertson are among those speaking at the conference in the afternoon.

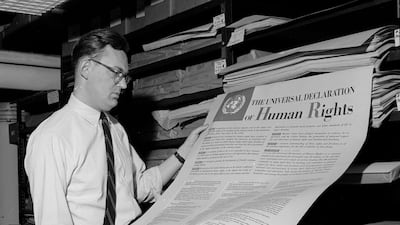

The Central Hall still bore shrapnel scars from the Second World War Blitz at the time of the first UN meeting in 1946. Delegates from 51 nations attended the session to define the scope of the newly formed multilateral organisation that emerged after the two devastating wars.

As he opened the meeting, Eduardo Zuleta Angel, Colombian foreign minister at the time, said delegates had come to London “determined to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war, which twice in our lifetime has brought untold sorrow to mankind,” and with an “abiding faith in freedom and justice”.

Clement Attlee, then prime minister of Britain, stressed that the UN charter was not simply an agreement between governments and states, but a reflection of the “simple, elemental needs of human beings whatever be their race, their colour, or creed.”

The gathering then elected its first president, Belgian Paul-Henri Spaak, who defeated Norwegian foreign minister Trygve Lie, who was backed by the Soviet block.

Crisis in confidence

But delegates and members of the public attending the anniversary on Saturday will be thinking of the organisation’s future, as it faces the biggest confidence crisis in its history.

“Now we are the time where a number of things are calling people to question the relevance of the UN. It’s related to a much broader transition in global politics,” said Jane Kinninmont, chief executive of UN Association of the UK (UNA-UK), which is organising the anniversary commemorations. More than 1,600 people have signed up for the events.

Growing nationalist and populist sentiment in the UK and Europe has caused a creeping disillusion with the UN – and multilateralism – to fester. “Right now there’s a very widespread zeitgeist that things are going wrong in the West and that the West needs to reassert itself,” she told The National.

But there are also concerns as global conflicts multiply, that some member states are being too “permissive” in attitude towards international law, Ms Kinninmont said. In recent years it has been the smaller countries bringing war crimes cases to the courts in The Hague, she added.

US President Donald Trump made huge cuts to overseas aid spending, and further cuts are expected from the UK and other major European donors. The organisation was told to “adapt or die” by US foreign aid secretary James Lewin as he pledged a further $2 billion in funding last month, with restrictions on sending aid to Yemen or Afghanistan.

An incoming secretary general, who will be announced later this month, will need to address these crises.

Although budget cuts were expected, more work was needed to make sure these were made efficiently, Ms Kinninmont said. There is also the continuing debate over the veto powers held by the five permanent members of the Security Council, which critics say is outdated and paralyses action on major conflicts such as those in Syria and Russia.

Historic support

In a speech at the General Assembly in September 2024, UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer spoke of his “deep belief in the principles of this body and the value of international co-operation”.

Public support for the UN and its values of international law and peacemaking has always been high in Britain. “There is a deeper public support for the international system,” Ms Kinninmont said. Polling by the Pew Research Centre found that 66 per cent of people in the UK view the UN favourably, slightly more than the 25-country average of 61 per cent.

But a rise in populist politics and a cost of living crisis could change that. Leader of the Reform party Nigel Farage last week said the UK should follow the US’s lead and quit the UN climate agreements.

“The UK is in a really interesting time. The government has expressed commitment to international law but is also worried about the extent to which the public cares, when everybody is thinking about their doctor’s appointment and the cost of living,” Ms Kinninmont said.

She urged people to think differently about these issues. “These things are linked together: if we live in a more dangerous world with more wars, more of that budget will be spent on defence, and that will take money away from welfare, health and education,” she said, adding that rising food costs were also linked to global crises.

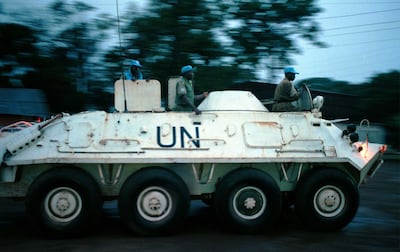

Security co-operation

There are also calls for US President Donald Trump to keep the UN and its multilateral system at the core of security and counter-terrorism efforts.

Counter-terrorism experts Dr Matthew Levitt and Michael Jacobson urged Mr Trump to work closely with the UN in its coming review of the 2006 Global Counter-terrorism Strategy later this year.

“Leveraging multilateral organisations to drive preferred agendas can be challenging, but this practice has repeatedly helped America build consensus and momentum on its priority issues, particularly the threats posed by [ISIS], Hezbollah and Iran,” they wrote on Wednesday.

“Turning away from multilateral counter-terrorism co-operation would cede this space to adversaries such as Russia and China.”