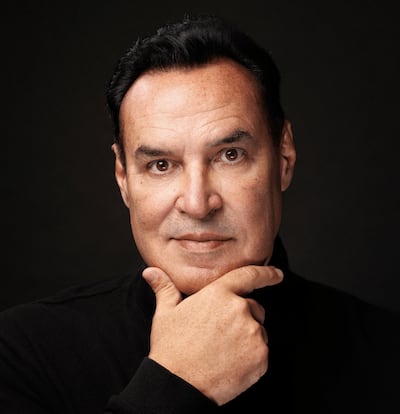

David Lesperance pauses for a moment as he considers his answer.

“Probably a couple of hundred,” he replies. He is talking about the number of ultra wealthy people he believes have left Britain in recent times for a new life in places such as Dubai.

He’s doesn’t mean millionaires, either. He is referring to people worth £500 million-plus ($675 million) and approaching the dollar billionaire bracket that he or his contemporaries, as international tax experts, have advised on their departures.

Festive greetings now include the phrase "can't wait for Dubai", as used by the husband of Petra Ecclestone, heiress to the multibillion-dollar Formula One fortune, before the Christmas break. Petra and Sam Palmer retain homes in Chelsea and Los Angeles but are reportedly setting up in the Gulf.

For all the talk of 250,000 people relocating abroad in the past year and predictions that 16,000 millionaires would depart in 2025, it is those seriously wealthy people ditching Britain he believes should truly worry the UK government, or rather those in the Treasury trying to balance the books.

And in a message that should sound alarm bells for Rachel Reeves, the Chancellor, he says the tide is not yet turning. More billionaires are heading for Dubai, leaving a very large tax hole in their wake.

It is a topic that has also worried former UK prime minister David Cameron, who said at Abu Dhabi Finance Week that the Labour government should do more to stem the flow.

The record tax-raising November budget may not have featured the much-touted exit tax but there was nothing in Ms Reeves' plans to persuade those already considering upping sticks to reconsider, Mr Lesperance says. The Sword of Damocles is still hanging over them.

“So, my clients are saying ‘yeah, she didn't announce one this time. But she's still going to need money next autumn’. My clients will still depart. But now, they can retreat from the UK in an orderly way. They don't have to rush to be gone by a deadline.”

The flurry of departures, which had begun in the dying days of the Tory government but appears to have gathered pace since Keir Starmer’s Labour took over in July 2024, is snowballing.

Wealth advisers The National has spoken to say relocating has become a regular conversation with clients.

Claire Spinks, global head of tax at international financial advisory firm Hoxton Wealth, said a year ago there was a balance between people returning or leaving. Now, it’s a different story. “We just don’t see people coming back any more,” she said.

What’s wrong with Britain?

While there are several reasons the super-rich may decide to move, Ms Spinks says there is one overriding factor: “The sheer weight of UK tax.”

She highlights income tax up to 45 per cent, capital gains tax (CGT) at 24 per cent, then, “right at the end”, inheritance tax of 40 per cent. It’s also a complicated system, with layers of anti-avoidance rules and the constant threat of change meaning “you’re never quite sure where you’re going to be taxed next”.

“Business owners are unsettled by constant rumours of CGT rises, wealth taxes, exit taxes and a very real reduction in tax reliefs,” she said. “There’s a concern that they tax the business sale, perhaps add a wealth tax or an exit tax, then ultimately tax the estate. That layering affects people.”

The removal of non-domiciled status from April this year, a Tory decision enforced by Labour, was a sign that Britain was becoming less appealing to the seriously wealthy international operators. Non-doms were UK residents whose permanent home for tax purposes is outside the UK, meaning they paid tax only on the money they earned in the UK. Any money made abroad was only taxed by the UK if it was brought into the UK.

Mr Lesperance, a lawyer and former non-dom who describes his job as integrated tax and migration adviser, said he had a conversation with a client in which he laid out the direction the government was heading with a tougher tax regime and got the reply: "London is nice? It isn't that nice."

What is the impact?

One of the most high-profile non-doms was former prime minister Rishi Sunak’s wife, Akshata Murty, who rescinded that status after a string of unfavourable headlines from the left-wing media.

“She was kind of forced out of being non-dom for political reasons,” said Mr Lesperance. “But in the year before, her last year as a non-dom, she still contributed £6.4 million in UK tax. That's a lot of doctors and nurses and teachers.”

He describes these high taxpayers as Golden Geese. He acknowledges millionaires will contribute more than the average, “but you get somebody like [Lakshmi] Mittal, that guy's contributing, like, 4,000 times the average”. The 75-year-old Indian steel magnate with a personal fortune of £15.4 billion had lived in the UK since 1995 but recently decided to move to Dubai, reportedly due to concerns over inheritance tax.

“So the loss of a tiny number of [billionaires] has an asymmetric negative impact on annual tax revenue,” said Mr Lesperance. “Not only do you not get the windfall, you actually lose a significant hit of your current income. And that's just the nature of a progressive tax system.

“Whether you think it's fair or not, that's the nature of that revenue model. In the UK, the top 1 per cent contribute 30 per cent to the total annual tax take. I won't argue with the fairness of it. I'll just say that that's a particularly unstable revenue model if you lose a lot of those 1 per cent.”

The exact amount of tax lost through the departure of a billionaire is difficult to calculate and would vary with each individual, but Mr Lesperance is sure of one thing: “The departure of a tiny number of them has a big impact.”

Businessman and philanthropist Lord Michael Hintze, who has significant investment interests in the UAE, speaking days after Ms Reeves delivered her second budget, warned that failing to support "those who produce, invest and innovate" would endanger the "very foundations on which fairness and opportunity rest". He cited the work of British Nobel laureate Sir James Mirrlees, who explained why incentives matter. He said in the House of Lords: "When marginal taxes rise sharply, high-productivity individuals reduce effort, invest less or relocate their activity beyond the UK.

"Recent examples, such as the relocation of wealth creators such as Mittal, are not ideological anecdotes but precisely the behaviour that Mirrlees predicted 50 years ago. It is a principle. As a nation, we are poorer for these people leaving – not just billionaires but the young strivers who are leaving these shores to make the UAE and other places in the world richer, not us."

Life inertia v tax savings

Those staying put are the “mass affluent”, with a few million to their name from small business or health practices, who are reliant on an established local set of customers.

So, who is leaving Britain? Seemingly everyone is considering making the leap, if posts on LinkedIn or right-wing media are anything to go by.

In reality, there are two types of people drawn to setting up a life in a country like Dubai, according to Mr Lesperance.

“Young people who don't see an economic opportunity for themselves in the UK and see Dubai as a boomtown, for employment and career. They're definitely moving,” he said.

The other group are the super-rich, who are already global citizens. “Generally speaking, the wealthier you are, the less you need to be at one location to make and maintain your wealth,” he said.

“So, if you're Nik Storonsky, for example, you don't need to be in London in order to be the founder and chairman of Revolut. Mittal doesn't need to be in London in order to [run] a global empire.”

Russian-born FinTech magnate Mr Storonsky has changed his residence from the UK to the UAE, according to regulatory filings. His relocation was effective a year ago but came to light in October.

The decision in making the move comes down to push-and-pull factors – does the tax saving or lifestyle opportunity beat the "life inertia"? – which is where Dubai plays a particularly successful role.

It’s about balancing finding the right tax jurisdiction to meet your needs against issues such as family, schools and social life.

If you just want to reduce your tax bill, you could move to the Channel island of Sark, says Mr Lesperance, but you wouldn’t find much to do, whereas Dubai ticks several boxes.

And there is also the snowball effect. Once friends and colleagues prove moving to the UAE can work, it becomes an easier decision for others.

Ms Spinks said there is a “tendency” to move where the client is, especially for those in professional services. ”While we’ve seen this exodus to the UAE, it’s going to mean those professions dealing with them also want to have their business based there.”

What can be done to keep them?

Reversing the tide to keep hold of the super-wealthy, or indeed attract more to the UK, would give the Labour government another income source. But how to do it when your own MPs and voters want to see those with the "broadest shoulders" paying more?

For Ms Spinks, the answer lies in creating a long-term tax policy, ending speculation of what’s coming next and understanding that taxing everything triggers people to protect their money. She would like to see incentives for business to employ more people.

Mr Lesperance, meanwhile, wants to ensure that an exit tax or wealth tax are off the table, as they are complicated and inefficient.

He would like to see an investor programme to give relief to those taking a risk on founding a business, encourage philanthropy, or match fund growth projects.

If the government does not find a tax system the super rich can live with, then the UK should get used to having fewer of them.

“Those golden geese, they’ve got wings,” he says.