Rime Allaf had planned her “ideal first evening” when she returned to Syria in October for the first time in more than a decade: she would go for dinner at a small restaurant near her grandmother’s house known for its fatteh and other “homey” Syrian dishes.

The Vienna-based author of a new history of the Syrian civil war, It Started In Damascus, had not expected to be able to return to her home country after the former regime of Bashar Al Assad erased her identity from its records in 2011.

But when she finally did, she wanted to experience the everyday things she had missed, and spend time with her cousins. “I wanted to be back home, to walk in the souqs, to buy food there … not being in a hotel in that little bubble of expats,” she said.

Overcome with emotions when she arrived, she instead spent her first evening walking around the neighbourhood near her family home in Abou Rummaneh.

There was relief at feeling safe and free in Damascus for the first time and to see the new Syrian flag, adopted after the ousting of Mr Al Assad on December 8, 2024.

“To be there and to know that it was perfectly safe. To see that flag. It makes you extremely emotional,” Allaf said. But she was also struck by the degraded living standards. “Sidewalks had become crowded, messy, louder than ever,” she added.

Around her, people were hopeful that things would get better very soon as western sanctions are lifted, but also “suffocating” from the years of economic isolation and war. “What was very difficult was seeing with your own eyes just how neglected and distressed the country had become,” she said.

The electricity came on for up to five hours a day, which her family described as an improvement. There could be no running water for days, and when it did come it was only for a couple of hours. “If the water did not come at the same time as the electricity, then your pump would never manage to bring up the stuff.”

“Damascus is suffocating right now,” she said as she discussed the lack of new services and development over the last year.

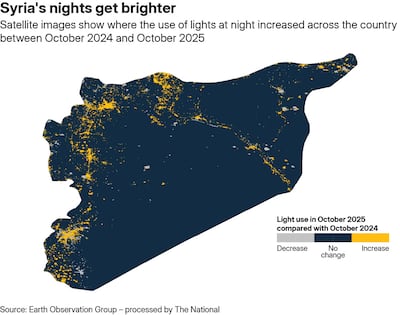

“If they were to see some rebuilding beginning, some social housing, some infrastructure, some lighting in the streets, I think that would give you a collective sense of hope, that [the international community] kept its word.”

How Syrians got there

The collapse of the Assad regime has been likened to the fall of the Berlin Wall, when a population living for decades under an oppressive, isolationist government with a sprawling security apparatus was finally able to speak freely and decide on its future.

Allaf was working on the two final chapters of her book when Hayat Tahrir Al Sham, backed by other opposition forces, began its advance towards Damascus.

She was given an extension to watch developments in the weeks that followed, and her thoughts on these are reflected in the book.

As attention focuses on the country's future, Allaf’s new book aims to tell a mainstream audience how Syria got there. It begins with the death of president Hafez Al Assad in 2000, and her outrage at her family’s instinct to mourn him despite their long criticism of his rule.

She then traces the three decades of Hafez’s rule, his son Bashar’s succession and the false hopes of reform, through to the peaceful uprisings of 2011 and the civil war which led to the largest displacement crisis seen since the Second World War.

The book outlines in detail US president Barack Obama’s U-turn on his “red line” over the use of chemical weapons – which Allaf views as the “real cut-off point” for the civil movement against the Assad regime.

In 2012, Mr Obama, whose administration had privately been reassuring Bashar Al Assad that he would not be forced out power, said that chemical attacks against civilians would be the red line that would force the US to intervene.

But when those attacks happened in 2013, no intervention took place. This was followed by Russian entry into the conflict in support of Mr Al Assad, and US negotiations with Iran to curb its nuclear ambitions in exchange for sanctions relief.

Iran-backed militias including Lebanese Hezbollah, funded by a newly enriched Tehran, were emboldened to wreak havoc on Syria and the region.

“This is a turning point. Assad had been warned but the consequences were not carried out. Putin was given free hand in everything, and the US focused on this nuclear deal,” she said.

“When we were in the midst of all this, it was so hard to see the trajectory of how things went from bad to worst,” she said.

This why – despite the radical changes that have taken place in the past year – the story of the regime’s final decade will continue to be important to readers seeking context for the present.

Identity recovery

Allaf was born in Syria but spent her childhood in New York, Geneva and Vienna. She was an associate fellow at the UK foreign affairs think tank Chatham House when the war broke out in 2011, and is now an independent adviser on geopolitics and communications.

Her father, Mowaffak Allaf, was a respected international diplomat who served as the first Arab Under-Secretary-General of the UN, and headed the Syrian delegation to the 1991 Madrid peace conference and Syria's subsequent border talks with Israel.

In the book, Allaf describes one her family trips in the “dark, stifling 1980s” in Syria, when fellow motorists were “afraid” of getting on the wrong side of her father’s diplomatic car. Her parents had warned her and her brothers to “see nothing, hear nothing, and above all say nothing – especially in public”.

But for over a decade, Allaf’s name did not exist in Syrian government records. Her national identity number was erased in 2011 due to her vocal criticism of Bashar Al Assad’s regime from London, when the uprising against him began.

When she returned to Syria she was met with confusion at an administrative office when she requested a new number. It was eventually decided that they would issue a new one, a decision she believes to be unique.

She began writing the book in 2023, motivated by a sense of alarm that Mr Al Assad was being rehabilitated by the war-weary Arab world, and the fear that Europe, responding to popular backlash against refugees, would soon follow.

In May of that year, Mr Al Assad was welcomed for the first time in over a decade to the Arab League Summit.

The normalisation was part of a failed bid to get him to crack down on the Captagon trade. The highly addictive amphetamine was being produced in Syria and trafficked to the Gulf by forces and individuals linked to the cash-strapped Assad regime.

Meanwhile, far-right groups in Germany and Italy, who had long courted the regime in order to claim the country was safe for returns, were gaining ground at elections.

European states increasingly sought avenues for the return of Syrian refugees to the county.

“That is the point when I thought everything's under the rug. It's over,” Allaf said. “Most of the world couldn’t wait to follow through [with normalisation].”

Aftermath

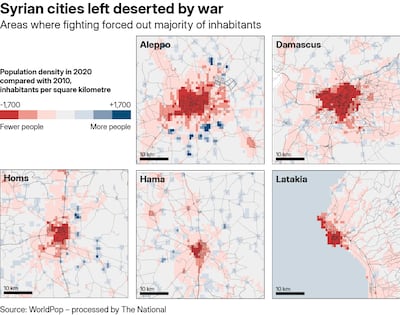

The euphoria over the Assad regime’s collapse cannot undo the years of devastation that preceded it: the destruction of major historical cities, the use of chemical weapons, 600,000 killed with hundreds of thousands more missing, and the flight of half of the population.

Many look back with sadness on the initial weeks of the Syrian revolution and wonder why the fall of the Assad regime did not happen then, when a widespread civil movement was first mobilised in the country and in the region. “We could have had it the way we always wanted it at the beginning, I felt this all along, for 10 years,” she said.

The uprising against Assad had been organic and involved every part of Syrian society. “We had doctors, lecturers and writers and a representative from every geographical area.”

Assad supporters were not the only ones to blame, she says. The book outlines how western diplomats and media lionised Bashar and celebrated his British-born wife Asma for years before the war.

The opposition had also failed, by focusing too much on “arbitrary” conditions set by the international community to secure their support. “For years, the opposition tried to satisfy western and international demands, which were arbitrary and as if they were going on a checklist,” Allaf said.

The new Syrian authorities have made huge gains, building relationships with the US, Arab world and Europe, and successfully pushing for crippling sanctions on the country to be lifted. However, there are concerns they could backslide towards authoritarianism.

Allaf is optimistic for the long term, but says the struggle continues. “Many Syrians believe that the revolution is not yet over, despite Assad’s escape. They will be waiting to reach this desired state of equality and law,” she writes.

“Like with every society that has had to argue and climb its way to democracy, the coming period in Syria will not necessarily be calm as they seek their peace, knowing that peace without justice is not peace, and that justice without accountability is not justice.”