Berlin is famous for its walls and for decades a select group of people have treasured lumps of its former Cold War dividing line.

There is something appropriate about a chunk of wall from the Berlin studio of Marwan Kassab-Bachi sitting at the heart of a blockbuster exhibition of his work at Christie's in central London.

Christie's Middle East

The Mayfair institution has been taken over by a display of Marwan's work that does full justice to his long career, which was almost entirely based in Berlin.

It was his roots in Syria that helped to shape his work.

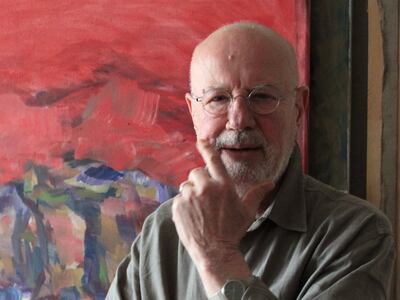

A practitioner of art as an enigmatic expression of the soul, Marwan is seen by Christie's curator Ridha Moumni as working out a deep attachment to his Syrian childhood in his paintings.

Not least in the breakthrough period of his work when Maran painted many heads reclining but with an identifiable landscape on the canvas.

You can take the boy out of the foothills of Mount Qasioun but for the painter it was a lifelong resource. The exhibition sets this up with a series of almost monochrome postwar Berlin photographs by the famed Henri Cartier-Bresson.

The chairman of Christie's Middle East and Africa has chose Marwan: A Soul in Exile as the third Christies summer series on art of the Arab World.

Works like the Parisian Head in 1973 or Kopf moved the focus to the head with rich, deep French-inspired use of colour to show how he brooded on his past, almost like a man lost in thought staring into a mirror. The mountain is never depicted but its brows and ridges are reflected in the flesh.

"The head is mixing directly with the landscape," says Mr Moumni at one point of a tour on the opening morning of the month-long retrospective. "He acknowledged that the faces and the heads that he's painting all his life are part of the mountain. The mountain is the core of his painting - the–mountain is his soul staying in the landscape and in the soil of Syria."

From the 1967 war through to the outset of the 1970s, Marwan's work took on a political dimension with piece such as The Disappeared, where handkerchiefs and scarves covered the faces. There was also the haunting Three Palestinian Boys in 1970.

"When the veil comes over the face it is almost a feeling of the disappearance but also a feeling of covering the face in front of the atrocities of the world," said Mr Moumni. "This is a very, very strong and impactful painting from 1970.

"The Three Palestinian Boys is a painting that was displayed very extensively through his life and it is not only a work on that did not only on the displacement but what he wanted to do was a representation of the Palestinian voice. This is why he represented them from below."

The dramatic perspective flips Marwan's usual order with big bodies and small hands and, crucially, heads. Typically the head or the face dominated his work but not in this case.

Meanwhile, as the decade progressed he would go on to develop portraits of political figures such as the Syrian Munif Al Razzaz or the Iraqi Badr Shakir Al Sayyab.

Intimate artist

Marwan eventually resumed his direct relationship with Syria. He was not banned from his home country, although he had suffered the schism of his family land being seized not long after he started studying in Berlin in 1957.

A trove of his correspondence in Arabic forms a side exhibit and is as illuminating as the body of paintings. "Marwan was very poetic in the way he was writing -he was really writing almost like a poet," he added. "He was writing these letters in Arabic to people and showing that reading and writing in Arabic and using Arabic letters and its literature was very important for him."

Homeward bound

In the 1990s what had been an intermittent relationship with the Middle East and his work – he exhibited at the Arab Cultural Centre in Damascus in 1970 – came to be a part of his career.

A portrait of Mona Atassi, the driving force behind the Attasi Foundation, by Marwan is part of the exhibition for that reason. As director of the summer academy at Darat Al Funun in Amman, he became a mentor to a generation of Arab artists.

In the decade before his death in 2016, Mr Marwan honed in on the face and in these paintings what surrounds the faces are telling, according to Mr Moumni. In this as elsewhere in his work there are hallmarks of a Cezanne influence.

"What you see around [the face] is the question of the soil but also the question of the death," he explains of one work. "The hair is creating almost a continuity with the landscape and here it's almost a wall, almost a darkness created by the idea of the afterlife."