For Father Andrew Hochstedler, Pope Leo’s visit to Turkey recalls his favourite childhood novels, the Chronicles of Narnia. For him, it is as if Aslan the lion is coming.

“Aslan in the book is a symbol for a Christ figure,” the parish priest at the St Anthony of Padua church told The National. “The Pope is the servant of all servants, he is the leader of the church. He's representing Christ on Earth. So there is that connection.”

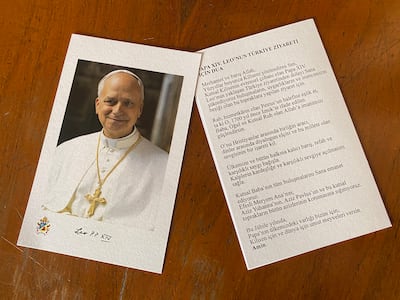

Outside, the Holy See’s flag has been hoisted up the side of the 113-year-old church building, on the bustling Istiklal Avenue shopping street in central Istanbul. Inside, cards bearing Pope Leo’s face have been prepared with a prayer in Turkish for his visit.

The leader of the world’s Catholics will head to Turkey on Thursday and then to Lebanon, in his first overseas trip since his appointment in May following the death of Pope Francis. In Turkey, he will visit Istanbul's renowned Blue Mosque and make a stop in the city of Iznik, where in the year 325 a council of bishops created a basis of beliefs still used in Christian worship today. In Lebanon, in the shadow of renewed Israeli air strikes, Pope Leo will visit churches and hold a prayer at the site of the 2020 Beirut port explosion.

There is a palpable excitement among Turkey’s Catholic and wider Christian community about Pope Leo’s long-awaited visit to the country, whose territory is dotted with sites from the religion's history. There are no concrete figures for Turkey's Christian population, though the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom estimates that under one per cent of the country's 86 million people are non-Muslim. That figure also includes Jews, Yazidis and other faiths.

For such a small community, Pope Leo’s visit is a chance for them to feel seen. “He will bless us, it’s a lovely thing,” said Filiz, a 50-year-old worshipper at a church in western Istanbul. “Even if I can't talk to him, he will have seen us. We will be in his aura.” The National is printing only the first names of Christian churchgoers because of fears about a possible backlash if they speak out about their religion.

“Catholics are a small minority, but the whole country is moving – the President, the church, and Christians feel that they belong to a bigger community,” said Father Paolo, a priest who has been based in Turkey for a decade. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan will welcome Pope Leo in an official ceremony in the capital, Ankara.

Meeting the logistical challenge of welcoming the Pope – the fifth holder of the office to visit Turkey – is an act of interfaith relations in itself, Christians believe. The last papal visit to Turkey was by Pope Francis in 2014.

“Even Muslim policemen are putting everything on the line for the papal visit. They are providing everything for security, for the organisation of the mass,” said Nikol, another churchgoer in Istanbul, referring to a large-scale prayer that the Pope will lead at a stadium in the city. “So there is actually a unity here, even if involuntarily. Everyone is helping.”

Turkey’s Christian minority hopes it will build trust and interfaith relations with the Muslim majority. Pope Leo has made statements on issues that rouse strong feelings among Turks, including on the war in Gaza. In September, he said there was, “no future based on violence, forced exile, or vengeance”, in reference to the crisis in the war-torn strip.

“This Pope is working for peace and has spoken out about the situation in Gaza, which is a sensitive issue,” said Father Andrew, who was born in Turkey to US parents and speaks fluent Turkish. “So I think that there's a sense his coming will say to the people around us, we're on your side.”

There is also a sense of spirituality in Turkey that transcends different religions, stemming from beliefs in the power of holy men regardless of creed. The majority of people who come to ask Father Andrew for blessings are Muslims, who often ask for partners for their children or healing from physical or mental sickness. Others come to simply ask questions, including, recently, a young imam from the city of Izmir.

“There are no qualms about asking a Christian to pray for you precisely because you're praying to Jesus, who is a healer, who is a prophet,” said Father Andrew.

On paper, Turkey is a secular country and has no state religion, although some observers suggest the rule of Mr Erdogan, a devout Muslim, has propelled forward the dominance of Islam. Church authorities face major problems because they have no official legal status in the country.

“I think that's one of the most concrete, biggest difficulties, because how do you operate when you're not recognised?” said Father Andrew at the St Anthony of Padua Church.

Conversion from Islam to Christianity is legal, and some of Turkey’s Christians used to be Muslims. Yigit, 17, grew up in a Muslim family in Istanbul but decided to convert. He said his family supported his decision, but added that he was “lucky”.

“My mother went abroad and she bought me Christmas presents of rosaries and statues of Jesus, since there are not many of them here,” he told The National. “So they gave me a lot of freedom in this regard.”

But even with his family’s support, he feels nervous about openly showing signs of his faith, and he hides the cross pendant he wears when riding the city metro, for example. Christians have been openly targeted in Turkey, including in a fatal gun attack on a church in Istanbul last year.

Despite the difficulties, Turkey’s Christians are buoyed by the idea of Pope Leo’s presence in the country, and for its potential to build Christian-Muslim ties. The visit is perhaps “a sign of love for Muslims too”, said Nikol, one of the churchgoers. “Because the Pope coming here is actually an expression showing that everyone is one.”