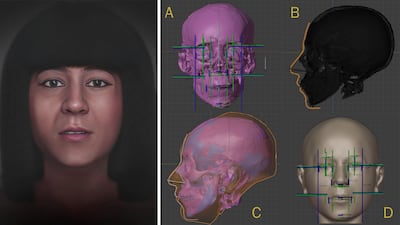

The lines on the 3D computer-generated skull might appear to be the guidelines of a surgeon preparing to operate. Markers denote the thickness of the soft tissue, the profile of the nose and a deformity near the jaw.

But this is not a patient set for plastic surgery. It is the outline scans of an ancient Egyptian mummy called Meresamun, whose face has been recreated despite her resting in an unopened sarcophagus at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford.

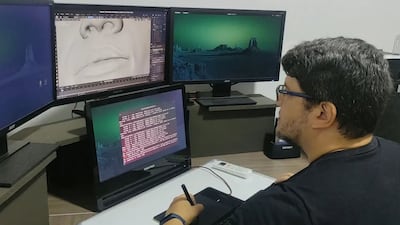

It is the work of a remarkable Brazilian – part artist, part scientist.

Cicero Moraes, 42, has rebuilt the faces of historical figures such as Beethoven, Mozart and Dante, as well as the "delicate, rounded" face of Egyptian pharoah Tutankhamun.

He recreated the face of 13th century Portuguese monk Anthony of Padua, and Latin America’s first saint, Rose of Lima. He has used the technique to create plastic limbs for injured animals, support police investigations and to help surgeons operating on real-life patients.

It is a hobby that began more than a decade ago after Moraes was grazed by a bullet in the head when he tried to protect his family from an armed robbery, and began experiencing symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder.

Already a talented graphic designer, he taught himself how to do facial reconstructions, or “facial approximation”.

“I was always a ‘nerd’ who loved computer graphics and studying," Moraes told The National.

"To cope, I did what I’ve always done during difficult times: I immersed myself in studying something meaningful. At that moment, I felt a strong urge to learn about forensic facial approximation.

"I committed myself deeply, and two years later I was hired to perform 24 facial reconstructions for an exhibition in Padua, Italy – including the face of Saint Anthony of Padua.”

As his work grew, he was contacted by doctors and plastic surgeons preparing for highly complex facial reconstruction surgery, including cancer patients, and by the police requiring post-mortem identifications. He then moved on to historical figures before pulling off one of his most difficult assignments, an Egyptian mummy still inside her sarcophogus.

Moraes, who is based in the town of Sinop in the heart of Brazil, was captivated by the ancient Egyptian priestess Meresamu.

He was drawn to her life as a member of the Thebian elite who played a key cultural and spiritual role in her time, as well as the fact that the data from the CT scans had been put in the public domain for other researchers to use.

The symbols on her colourful coffin indicate she was a priestess and woman of high rank in the ancient city of Thebes, living about 800BC under the rule of Egypt's 22nd dynasty.

Her official title indicates she was a singer inside the Temple of Amun in Karnak near Luxor, and her name means “Amun Loves Her". The major Egyptian deity was thought to be the King of the Gods, and was fused with the Sun God Ra.

Her singing was so valued that after her death, she was depicted wearing a vulture headdress in an elaborately decorated sarcophagus.

Computed tomography (CT) scans by the University of Chicago, taken in 2012, allowed scientists to peer at the human remains wrapped in the papyrus. Those scans, which were made publicly available, were the basis for Moraes's reconstruction. He said the mummy was “remarkably well preserved”.

His technique involves arranging the skull in segments, applying markers for soft tissue, and then nasal and profile projections.

The resulting base face is then digitally sculpted. Soft tissue markers were applied to the 3-D scan of the skull to design the lips, nose and other features, guided by data from living people. A CT scan from a living donor was then combined with the resulting image, to reflect the mummy’s appropriate age, skin tone and texture.

Meresamun was given a fringe and bob haircut, inspired by ancient Egyptian art.

Moraes used estimates from the CT scans about the size of Meresamun’s head and her body weight. She is believed to have been shorter (1.47 metres) and with a larger head than the average women of her time.

It can take two weeks of full-time work to develop each facial reconstruction, and the software that he developed to do them is distributed for free.

Leaps and bounds in the available technology help make Moraes’s work more accurate, he explains. Attempts to rebuild Meresamun’s face began in 2009, using “manual or hybrid techniques, even when digital", he said.

Today, with specialised algorithms, increased computer power and robust anatomical libraries, a higher degree of anatomical simulation can be achieved.

“The final result is a serene and harmonious face, conveying dignity and subtlety. Aesthetic dramatisation was avoided in favour of anatomical plausibility and historical respect,” Moraes told The National.

No reconstruction can ever be like for like, he explains, as a “degree of speculation” is required, but the estimates that he used were “scientifically grounded”.

He claims he has no favourites out of the 150 reconstructions he has completed.

“I'll be honest, I like everything I've done because I somehow learn or execute something I appreciate.

“At 39, I was identified as a gifted and highly skilled person with an IQ of 142. IQ alone doesn't mean much, but the fact is that, thanks to this I was able to enter academia and make many formal publications about my work. Today, in addition to facial reconstructions, I do other research and develop a solution for human surgical planning, used by surgeons in 33 countries.

“Keeping my mind active is essential for me, and seeing projects being executed brings a lot of joy, especially when I make new friends, in the case of facial approximations, or when I see lives being restructured, as in the case of surgical planning.”

Moraes says that surgical planning is his greatest challenge as he is dealing with real lives and any error could put them at risk.

“Fortunately, everything has worked very well, and we have helped people from babies to the elderly with these tools.”

But a highlight of his career has been in 2016, when he made a prosthetic shell for a turtle who had lost hers from burns in a fire. He worked closely with a team of vets to reconstruct the old shell, which was then 3-D printed and placed on the turtle.

The method has also been used for prosthetic toucan, goose, parrot and macaw beaks.

Moraes said he often gets a "positive" response to his work, but that his reconstruction of religious figures have also sparked "intense debate". But that does not deter him. "Even so, these moments have led to open and enriching academic dialogue," he said.