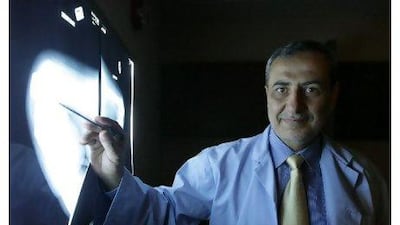

In the prime of his career, Syrian-born Samih Tarabichi, was based in an area many orthopaedic surgeons would describe as paradise.

He and his brother set up practice in a suburb of Tampa, Florida, the migratory home to thousands of so-called "snowbirds", a sobriquet applied by locals to the retired northerners of the United States who show up each winter for a bit of sunshine, golf, and, not infrequently, a hip or knee replacement.

It was a shock, then, when Dr Tarabichi announced in 1996 his plans to up sticks and move to the American Hospital Dubai on the other side of the world.

The sceptics included his brother, his US colleagues and former medical school classmates, and even the physicians he spoke to who were already practising in the Middle East.

"I was told this was not going to fly in this region," he recalled this week. "They said, 'You are going to be depressed.'"

Their argument was there was simply no demand for joint replacement surgery, which was Dr Tarabichi's speciality. It was a well-established fact, they said, that people in the Middle East did not want the procedure. And if they did want it, he was told, they flew to Europe to get it.

Dr Tarabichi carried on regardless, willing to take a hit to his career to allow his four children to see their grandparents more often, although he privately negotiated a deal to allow him to return to the US once a month to operate and earn a little extra money.

In his first full year in Dubai, Dr Tarabichi performed a total of seven transplants. This year, he expects to perform more than 700, a pace that, he says, probably makes him one of the busiest joint-replacement specialists in the world.

Dr Tarabichi is enjoying something of a moment. The Total Joint Replacement Center of Excellence, of which he is director, moved into a full floor of American Hospital Dubai's gleaming new building only five months ago. And last week he hosted a symposium of some of the world's leading surgeons, during which he outlined to his peers why the previous stereotypes of Middle Eastern patients were now misguided.

A few days later, sitting in his first-floor office looking out at the water slide peeking out the top of Al Nasr LeisureLand, he explained that it defies logic that Middle Eastern men and women would not want knee transplants.

"These people, if they can't bend the knee, this is going to be very distressful," he said, referring to the requirements of the five-times daily ritual of the call to prayer, as well as the preference of many south Asian men to squat on their haunches when they relax. Not to mention the fact that some even go to the bathroom in that position, too.

But it was not until several years into his Dubai residency that Dr Tarabichi realised the problem was not that people originating from the Middle East did not want joint replacements, but rather the available solutions were completely inadequate. To walk comfortably, it is not necessary for the knee to bend much more than 90 degrees. So the first artificial knees consisted of implants that bent 120 degrees at the most.

This was perfectly acceptable in the West, where joint replacement surgery was pioneered.

Not so much in the Middle East.

Working as a consultant to Zimmer, a US manufacturer of orthopaedic products, Dr Tarabichi helped develop knee implants that allow for "full flexion capability," or bending by as much as 150 degrees, enough for the recipient of a replacement joint to pray five times per day or relax comfortably in the grass or take care of any other business that may come up.

But that was not all. Dr Tarabichi observed that Arab knees are structurally different from those he had seen in the West. The femur bone is generally narrower and set at a slightly sharper angle, and the cruciate ligament more relaxed and malleable.

The discrepancy has since been verified in scientific journals.

"Not only is there a functional variation in the knee, there is also an anatomical variation," he said. The variations "are minor but they do have to be addressed."

Some specialists in the region have taken to calling the phenomenon "Arab knee" or "Middle Eastern knee", although Dr Tarabichi believes most Asian people share similar characteristics.

To address this, Dr Tarabichi is working with Zimmer to produce a wider range of implants. When artificial knees were first introduced, they came in three sizes - small, medium and large - similar to T-shirt sizes, but hardly an exact science. Zimmer is currently developing a range of 36 different sized replacements which he hopes to release next year.

The rapid growth of the Middle Eastern and Asian markets has helped to drive advances in joint transplants, although he notes that American patients have also revised their expectations.

"Initially (American patients) were happy to walk," Dr Tarabichi said. "Now they want to do gardening and they want to play with their grandchildren."

Dr Tarabichi says his latest challenge is to get Middle East residents to understand the wear and tear they put on their knees.

Most of the patients he sees in Dubai do not come to see him until it is too late and the knee joint is badly deformed, in part a reflection of the connection between obesity and arthritis.

"If they don't lose weight, they are going to wear out their knees, simply stated," he said.

Dr Tarabichi said studies have shown that exercise, believed by many to be destructive to the joints, actually helps prolong the long term health of knees and hips.

Asked about his own habits, he said, "I do exercise, but I am guilty. Sometimes I get too busy."