Three years ago, there was no such thing as the King Abdulaziz Camel Festival. What today is a sprawling six-week event that includes a much-lauded camel race and beauty contest, and hosts thousands of visitors and local tribesmen, was nothing but a vast desert expanse back then.

"In less than three months, we transformed it," says Tatiana Cadoux, an event director from Filmmaster Arabia, the company that was in charge of setting up and organising the first two festivals. "A stretch of sand that belonged to Bedouins suddenly had containers, stands, offices. We even built a water sanitation system."

Look through the gallery above to see what this year's festival looks like.

'I've never seen anything like it'

From the toilets to the generators and even the sewage system, everything was organised and built by Cadoux and her team in the first two years. They watched as roads and lampposts sprang up around them. A number of permanent structures were built, but the event consists mostly of temporary set-ups that are dismantled and installed year after year.

It hasn't been an easy job. "Logistics-wise, it has been a nightmare," Cadoux says. "For example, there's very harsh weather here. It's terrible. It can be 40 degrees in the day, super-cold at night, then sandstorms come – a wall of sand, like the sandstorm you see in Mission: Impossible Ghost Protocol. I've never seen anything like it anywhere else. All of a sudden you have to close everything up.

“We had to build structures that were very resistant to wind, most of them made in Europe, so we fly them in and install them. We had to make sure everything was very solid.” As the closest (small) city is 40 kilometres away, pulling all of that off was quite a feat.

Living in the desert

This week, the Frenchwoman, who has spent seven years working between Dubai and Saudi Arabia, is back in Rumah, Riyadh, where the festival is held, setting up the Royal Plaza. This is where the King of Saudi Arabia will, on Saturday to hand out prizes to the winners of the contests. While this time Cadoux has only been on site for two weeks, in the past two years, she has stayed in the desert for three months at a time, setting everything up with her team, then running operations throughout the event.

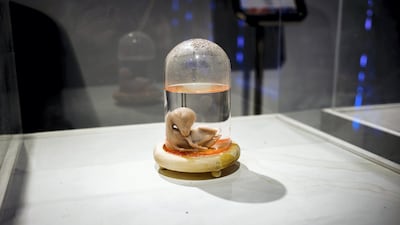

In 2017, the set-up covered about 5,000 square metres, she says. This year, it's twice that size, as it now includes activity centres, such as a Camel Museum and heritage village. The Camel Club has also invited guests from other countries to sell their wares and stage traditional performances. "They're trying to open it up to other world cultures and introduce nomadic approaches from different countries."

After spending so much time away from society working on this event, Cadoux says it can be hard to return to normal life once it’s all over. “You get so used to waking up in the desert,” she says. “You can take a 4x4 and drive for 10 minutes and see the most beautiful views – like the ones you see in the movies. We also go every day and pet the camels.

"I almost bought a camel once," she says with a laugh. "It was so cute. It was just seven months old and 'only' 50,000 Saudi riyals [Dh48,966]. They told me in a few years it'll be worth a million. Apparently that was a good price for a young camel that had potential."

Beautiful camels

Cadoux has learnt a lot about the traditions that underpin the rearing of camels among local tribes, particularly the custom of creating creatures worthy of winning beauty contests. She explains how it takes generations for camel-owners to breed a herd of dromedaries that look identical, and could potentially win the prize pot.

“I can recognise a nice camel now. There’s all this criteria for it to be beautiful – from the lip and how it hangs, to the height, to the legs, to the quality of hair, and length of the eyelashes.”

Last year, it was reported that a number of camels and their owners were disqualified from the competition for injecting Botox into the animal's lip, to make it appear fuller. At this year's event, medical professionals have been on hand to perform exams on the animals before the contest to ensure there is no cheating. These include ultrasounds, X-rays and blood tests.

While the camels are the focus of the event, Cadoux and her team have tried to inject a little style into proceedings, too. "It's my baby," she says. "We really tried to bring beauty to the place. I believe beauty is in everyone's soul."

They have done this by incorporating traditional elements of the local culture with more modern, sophisticated design touches. For example, they used sadu fabric – which is what Bedouin tents are made from – throughout the decor of the modern structures.

"We were given a lot of freedom to create the design," she says. "It's a festival, so you have to please the visitors – and these visitors are not used to festivals, so they were very happy with the smallest things. That, for us, was the most exciting thing, to see that whatever you were doing made them very happy."