Suddenly, there was Shiva. Golden brown, over 30 metres tall, he has a trident in one hand and a snake around his neck. Situated by the side of the road as he is, it's enough to stop traffic. We're here in Mauritius, just above the Tropic of Capricorn, some 4,000km from India and 2,000km from mainland Africa. Mauritius is Africa's farthest-flung nation, yet the deep influence of India is felt all over this island, and nowhere more so than here at Grand Bassin. Mauritius is Africa's only country with a majority Hindu population (48 per cent of a total of 1.3 million; the rest are made up of mainly Catholic Christians, 31 per cent, and Muslims, 16 per cent), and legend has it that here at Ganga Talao, as Grand Bassin is known in Hindi, Shiva spilt a few drops of water from the Ganges while protecting the world from floods. The Ganges apparently expressed concern at the loss of its water, but Shiva replied that dwellers from its banks would one day settle here and perform an annual pilgrimage.

And so it happened: every year, a vast three-day festival in spring, the Maha Shivaratri, attracts hundreds of thousands of devotees from across the island. Some walk barefoot to the lake. Today is just a normal day, but dozens of Hindus and a handful of tourists mill around the various colourful shrines at this rural spot in the hills of the south-west. They perform puja, ringing a bell on entering the temple, making offerings to the gods and being blessed by a priest. Tourists can, if they wish, be blessed too - and when they emerge from the temple the men have three horizontal white lines across their foreheads.

Significant Indian settlement began on Mauritius in the 1800s in less auspicious circumstances. After control by the Dutch and French, African slaves working on the island's sugar plantations were freed under the British but soon replaced with indentured labour from India and China. My young guide, Linzey Sophie-Aza, explains: "The British wanted control of Mauritius because French corsairs [pirates] were attacking its ships going to the East Indies. The French allowed Britain to take control of Mauritius provided they kept its civil code and allowed the settlers to keep their property. They kept the French language and the French kept [the island of] Reunion. Long after the British abolished slavery, the French wanted to keep it because of the plantations. So instead they got financial compensation and indentured labour."

A vast force of some 450,000 men and women from India was originally introduced to work in back-breaking conditions on farms and in factories all over the island. Yet they grew in influence, in time becoming citizens, owning land and eventually leading the fight for independence, which was granted in 1968. Today's Mauritius, with its mixed population, increasingly advanced economy and laid-back atmosphere, seems to represent an almost karmic balance to the hardships of the past. Linzey herself, calm and poised, is a mind-boggling array of cultures. "My grandparents are Chinese, my mother is French and my father is Anglican Chinese," she says. "Now I'm Catholic and Anglican." Before I can ponder how this can even be possible, Linzey is extolling present-day Mauritius' growing acceptance of mixed marriages. While ethnicity becomes increasingly diluted, Mauritian sense of identity seems to have become more intense. A white hotelier offers me a simpler analysis. "The beauty of this place is that no one here can say they are more Mauritian than anyone else. Prior to 1600 there was no one living here, we all came from somewhere else."

Strolling through the old quarter of the capital Port Louis, there are physical reminders of this extraordinary history. Bombay, Calcutta and Delhi Streets run into Sun Yat Sen Street, and old wooden clapboard houses surround French boulevards, British mansions, Tamil temples and a mosque built with Indian, Creole and Islamic influences. Following a general election the week before my visit in May, music boomed from a "thank you" party organised by the winning coalition - made up of the Mauritius Labour Party under Ravin Namgoolam, the Militant Socialist Movement under Pravin Jugnauth and the Mauritian Social Democrat Party led by Xavier Duval. Down the road, a small but noisy Hizb ut-Tahrir demonstration was taking place.

In the city's covered Central Market, a kalidescope of fresh produce from across Asia caters to Indian, Chinese, Creole and African tastes; the atmosphere is relaxed and I find myself wanting to stock up on produce even though that would be pointless. I drink in the scent of fresh herbs and vegetables each in a dozen different varieties before wandering around the old-fashioned meat market (in deference to the Muslim minority, most fresh meat in the country is halal). In a further nod to the subcontinent, the currency is the rupee (at one rupee for every eight dirhams, it's a third more valuable than its Indian counterpart). We make our way down to the sea and the city's large docks, which are marred by a rather ugly development called the Caudan Waterfront. Opened 10 years ago, I found it tacky and soulless, like a cheap Disney theme park - although there were some concessions to history including the nearby Postal Museum and Blue Penny Museum, which, along with the market and town centre with its different districts, all point to a past of trade, the constant importing and exporting of goods and people and everything in between.

It's a shame, then, that most visitors to Mauritius rarely venture outside the walls of their five-star resorts. One can see why - the country has until recently focused on high-spending tourists who demand excellent facilities, and with most coming from Europe either for a break from the winter weather or a honeymoon, there may be little need to leave their hotels. The drive from the airport to my hotel, along roads flanked by factories and the outskirts of Port Louis was certainly uninspiring and gave little idea of the island's beauty. Mauritius isn't, as I half-expected and which holiday brochures sometimes suggest, a giant version of an idyllic Maldivian island but a very real, gritty place with a developed economy and a large sophisticated population.

I'm staying at the Oberoi, a stunning ensemble of beautifully manicured villas near Balaclava on the north-west coast, yet a combination of factors including the weather, which has suddenly turned to winter, with its overcast skies and choppy water, coupled with indifferent service at the hotel, leaves me itching to get out. I'm glad I do. While most of Mauritius is covered with sugar cane fields, just a few kilometres away are the stunningly diverse botanical gardens in the pretty, small town of Pamplemousses. To give it its full name, the gardens are the Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam Botanical Gardens, named after the first prime minister of independent Mauritius. The place also houses the funerary platform where his body was cremated, but his ashes were scattered in India.

Here, among 37 hectares of parkland, are hundreds of varieties of trees, plants, shrubs and flowers. The centrepiece is a large pond filled with giant Brazilian lilies, and here Linzey gives me a potted history of the place. The gardens sit on the site where Mahé de Labourdonnais, the French governor of Mauritius (then known as Ile de France) who lived in nearby Mont Plaisir, created a vegetable garden. In 1767, an appropriately-named administrator, Pierre Poivre, took charge of the garden and introduced spices such as nutmeg and cloves as well as ornamental trees, but it was not until 200 years later in 1967 that the restored gardens were opened to the public.

It's a surprisingly beautiful place, with some 3,000 trees, including 80 types of palm tree and a 250-year-old baobab tree near the entrance gates, the roots of which destroyed a nearby building. Linzey shows me casaurina trees, used for charcoal, bottle palms and 80-year-old Agathisrobusta, or pine trees, a gift from England. In my mind I'm transported to a British period drama. "This Christmas tree is 135 metres tall and was also a present from the UK", Linzey goes on. "These are Chinese cypress trees, used to make coffins." She also shows me jackfruit trees from Asia, ylang ylang trees from Madagascar, enormous talipot palms from southern India, camphor trees, introduced to fight malaria, monkey puzzle trees from South America and the mysterious "bleeding tree" from Mozambique, a large tree with a thick trunk which sports "wounds" oozing thick red sap. "These are used in black magic," Linzey tells me. "The male tree bleeds more than the female but they mix them up to pretend that someone is cured."

Further into the grounds, there are some curious oddities - a "four-spice" tree, a mishmash of several different trees have been grafted together, and a tangled, distorted specimen which is the result of grafting together 14 types of mango tree. There is also the traveller's palm, which holds potable water in its leaves, and enormous Indian banyan trees. "The banyan tree never dies," says Linzey. "Even if you destroy part of it, it grows back." Beside the Brazilian lilies are native mahogany and ebony trees, which were comprehensively cleared in the wild by the European colonialists. There are lotus flowers from India and China and tilapia fish in the water, and the bright-red fruit of the sandal tree, also from India and used in dyes.

North of Pamplemousses is a string of pretty seaside villages running either side of Grande Baie, the north's biggest tourist centre. It's a laid-back but buzzing place, with plenty of hotels and restaurants and a scenic bay filled with sailing boats. I much preferred it here to Flic en Flac, the island's other major tourist centre on the west coast. There's a good-sized market, a Tamil temple and stalls selling dhol puri and roti chaud, and although there are some large hotels, they are set back from the coast and generally more human in scale.

Further east, the road hugs the coastline, snaking behind beaches backed with casaurina trees and yachts bobbing in the water. All of Mauritius' beaches are open to the public, but access seems better here: small stretches are packed with local families having picnics and playing board games and beach tennis. We stop at Cap Malheureux, a scenic fishing village with a church beside the sea and a small harbour. Linzey tells me that it was here exactly 200 years ago in 1810 that the British invasion force (with troops from India) finally defeated the French and took over the island. There's no sign of a bloody battle today: children play on a grassy lawn which stretches down to a shoreline strewn with rocks and fishing boats; out at sea is the distinctively-shaped island of Coin de Mire, now a nature reserve. Farther east along the coast, the landscape becomes more rugged, and with a wide blue sky stretching down to the sea and golden sandy beaches, it gets my vote for a place to escape the crowds. Doubling back on ourselves and heading south, I'm again struck by the sleepy picnic spots and some impromptu fish markets by the side of the road around Trou Aux Biches, a popular diving centre.

Heading south on our way to the interior, we pass the ever-present volcanic peaks behind Port Louis and sweep along the south coast, passing salt pans, mangroves and huge banyan trees next to tiny settlements. We turn inland and drive uphill into the Black River mountain range, looking back on Le Morne peninsula, where Linzey tells me a group of escaped slaves fearing re-capture jumped to their death in the 19th century, not realising that slavery had been abolished following their escape. The peninsula's history has earned it a place on the World Heritage list, but it's home almost exclusively now to tourists relaxing on package holidays.

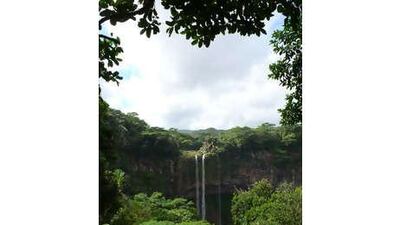

The road winds through Black River Gorges National Park and we stop briefly at the small village of Chamarel to view the "seven coloured earths", a site of cleared forest exposing rolling folds of volcanic earth of various colours - and one of Mauritius' most popular attractions. The surrounding countryside is gorgeous; with its thick forest, it's one of the few areas which show what the island must have looked like pre-colonisation. Close to the coloured earths is a lookout over the Chamarel waterfalls - a 100m drop surrounded by an Arcadian landscape of palm trees backing onto a forested plateau. Driving away from the site, the road turns to earth, footpaths cut through fields and bananas hang off nearby trees. We arrive at the Shiva statue at Grand Bassin, get out and have a look around before winding through the garden districts of Olivia and Sebastopol. We pass deep rivers and sugar cane fields which stretch all the way to the forest-covered mountains.

I can't help thinking again of how Mauritius has come full circle - of how the immigrants who changed the face of this island are now reaping the benefits of its growing tourist industry and of how much tourists stand to gain when they step outside their resorts.