Nothing is more agonising than watching your child slowly killing himself. I didn't realise just how painful a process it was until I spent a couple of days alone on a trip abroad with my 18-year-old son, who smokes. Wherever we were - in the airport, the hotel, a restaurant - he would be on edge. "Can we just wait to check in?" he would ask with moments to go before a flight closed, desperate to nip outside for a quick fag. If I insisted that this time we really couldn't delay, he would sulk and twitch until the plane touched down, then make a dash for the exit and light up.

That addict behaviour was merely irritating; his constant rasping coughs were far more upsetting. They took me straight back to my childhood when I used to lie in bed crying as, morning after morning, I listened to my mother in the bathroom discreetly - so she thought - clearing the phlegm from her smoker's lungs. I felt that familiar pricking in the eyes again as I heard my son already paying the price for his nasty habit. How did we get into this situation, I wondered? How can I prevent my younger children also becoming smokers? And, above all, how do I get him to stop before the habit becomes set for life?

Of course, I blamed myself, even before I started trawling the internet and came up with apocalyptic pronouncements such as this one from a stop smoking website: "Children generally take to habits like smoking because of a lack of communication between the members of the family and the children. You will be the party to their moral doom and ethical disaster unless you do something tangible, well in time."

I think we communicate quite well as a family but there is no getting around that fact that I used to smoke, and that having a parent who smokes is the single clearest predictor of children who smoke. I had taken it up, despite by anxieties about my mother's health, simply because there were cigarettes around. It was easy to take one or two and start experimenting. Once I had children I never smoked in front of them, only ever in the office, but despite washing my hair before I came home, they probably knew.

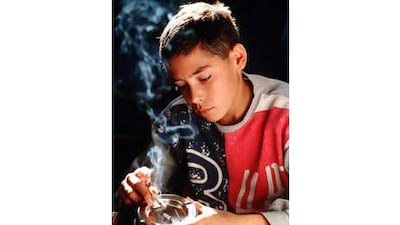

I was also perhaps blind to the early signs, not realising that although smoking is going out of fashion for educated adults, it hasn't among the young. More young people smoke than older people in developed countries. Despite the bans on advertising, age limits on tobacco sales and lessons about the health risks in school, teenagers and pre-teenagers still think it is a grown-up, rebellious, cool way to behave

My son was exactly the type to experiment with smoking at a young age. He wasn't sporty, nor did he like school, so he used to hang out with the other disaffected children. Around the time he started secondary school, he watched a very close family friend suffer first from emphysema and later from throat cancer as a result of smoking. He swore then that he would never take it up but I should have guessed he would try - and had probably already tried - cigarettes.

Perhaps at that stage I should have hammered home the studies which show that the younger someone starts smoking, the greater the risk of lung cancer, regardless of the amount smoked or for how long. It probably wouldn't have worked: teenagers are even more inclined to kid themselves that they are immortal than adults, but he might have responded to the argument that smokers are idiots who are being manipulated by cigarette companies. Teenagers distrust big corporations.

Early puffs are not only extremely dangerous to young lungs, they are also highly addictive. "The chances are that if your child tries a cigarette between the ages of nine and 12, they will go on to be a fully fledged smoker," according to John Dicey, a director of the Alan Carr stop-smoking programme. Knowing that, I would have tried bribery or threats - gating, withdrawal of pocket money - to make sure he didn't get hooked.

Soon it was too late. It takes only three tries at smoking for the insidious little buzz that nicotine provides to become lodged in the head. Then you have an addict and it is just as hard for a child to give up as for an adult. They soon develop the faulty reasoning that tells them they need a cigarette to face a difficult situation. Yelling is counterproductive. Demoralising a child or young adult makes them more likely to reach for a prop. Of course, I forbid him to smoke at home, but I can't prevent him hanging out of his window. I've left stop smoking literature around the house, but I don't want to encourage rebellion. Hugh Koch, a British psychologist who specialises in helping people stop smoking, tells me there are three ways a parent can assist children. I can help him understand why he started smoking, discuss the common misconceptions, such as the erroneous ideas that smoking is relaxing or aids concentration, and make sure he is aware of both the harmful consequences of smoking and the joys of not smoking.

I've done all that and he says he wants to give up, just not quite yet. There's always some difficult situation he has to face, and then he'll be brave. "I don't think it'll be too hard," he says. That's where I have learnt from Koch to put him right. It is tough. To succeed, you can't just stop from one minute to the next. It requires planning. It might be helpful to buy some nicotine patches or tell him to get a prescription for a drug which reduces cravings. Champix is the latest. A year ago it was authorised for use in UAE and elsewhere after trials among quitters showed a success rate of 44 per cent compared to 11 per cent for the placebo.

"It helps if you get the young person to focus on how they are going to manage their social life if their friends smoke," says Koch. "He could plan to spend time with friends who don't smoke." When he fails, as most do the first time they try to give up, I am all set to bolster his confidence. Koch advises those who feel they lack the willpower to try cutting down for a time before the next attempt to quit. If they allow themselves only half the number of cigarettes they have been consuming, and stick to it, they begin to feel in control.

Meanwhile, I have to accept that only my son can make the decision to stop. Seeing the state he has got himself into, however, I am yet more resolved to prevent my younger children taking up smoking. As an incentive, I have promised them each £1,000 (Dh6,351) if they reach 21 without having smoked; my eldest will get £500 (Dh3,176) if he gives up for at least 18 months before his 21st birthday. So far, the incentive seems to be working for the younger ones. They talk pityingly about their older brother and his habit. I hope I am not being fooled again.