A big-name star of stage, screen or the sporting arena can be the making of a brand, at least while the star is in the ascendant.

But if that star falls from the heavens, bound for the gutter with the tabloid press, the brand with which it worked must move swiftly to save its reputation.

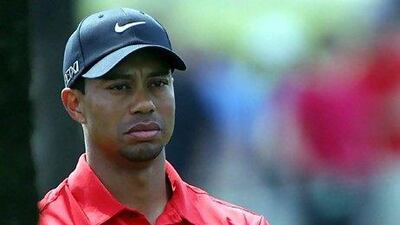

And many do. The golfer Tiger Woods, the model Kate Moss and former American footballer OJ Simpson are all prime examples of celebrities who have been cast adrift by big brands because of publicised bad behaviour.

Damage limitation exercises by branded goods companies are costly and time consuming, with no guarantee the brand will emerge unscathed.

Many experts believe stars who cheat on their partners, or become associated with illegal drug use and other crimes are often more memorable to the public than those who behave, prompting some companies to ask whether celebrity endorsements are worth it.

Donal Kilalea, the chief executive of Promoseven Sports Marketing in Dubai, points to reputational collapses of stars such as Simpson and Woods as indicative of the risk of personal endorsements.

Both Simpson, who was accused of murder but later acquitted before being jailed in 2008 for numerous crimes, and Woods, who cheated on his wife with a string of women, had lucrative sponsorship deals cancelled due to controversy over their private lives.

"If it goes right, it goes very right," says Mr Kilalea. "But once it goes wrong, it goes very wrong."

Such issues are increasingly relevant in the Gulf region, where there has been a boom in celebrity endorsements in recent years, largely due to the frenetic growth of Dubai's property industry.

Celebrities including Woods, the former tennis champion Boris Becker and former Formula One driver Niki Lauda have all been linked to Dubai property projects, not all of which saw the light of day because of the economic downturn.

Bashar Abdulkarim, the managing director of sports marketing and sponsorship consultancy at Relay Mena, says the value of celebrity endorsements in the Gulf has more than doubled in the past five years.

Associations with international A-list celebrities such as the footballer Wayne Rooney now typically cost up to US$1.5 million (Dh5.5m) a year for promotional work covering the Gulf region alone, says Mr Abdulkarim.

"You would spend anything from $1m to $1.5m just for the image rights for one year," he says. "It goes beyond that in terms of the perks and extras you have to pay."

Such fees can be worth it if celebrities stay on the straight and narrow, commentators say.

The golfer Rory McIlroy, who is the global ambassador of the Dubai hospitality company Jumeirah Group, has proved a highly positive association for the brand - despite his dramatic meltdown at the recent US Masters tournament, Mr Kilalea says.

"If he'd won the Masters, Jumeirah's brand would have benefited immensely. Even so, they still benefited," he says. "Rory McIlroy is so young, and he did so well on the first three days."

Large drinks manufacturers are among the most sophisticated in the Gulf at using celebrity endorsements, says Hermann Behrens, the chief executive of The Brand Union Middle East.

"The drink categories are the best in the endorsement space,"says Mr Behrens. "The war between Coca-Cola and Pepsi is really being fought on that level."

Yet celebrity endorsements in this market are not always a success. Woods was reportedly paid more than $55m by the UAE developer Tatweer to promote a golf resort in Dubai in a contract signed in 2006 and amended in 2008.

While the developer did not drop the sponsorship in the wake of the controversy surrounding Woods' private life last year, the golf resort was eventually cancelled.

Increasingly, contracts come with "moral" clauses, which allow brands to break a deal if celebrities do not prove to be sound role models. "They are a lot more careful in protecting their rights when celebrities do go off-piste," says Mr Behrens.

In sport, brands must be aware certain sports come with certain risks, says Mr Kilalea. "Cycling is a sport that suffers by association with drug-abuse allegations. There are rumours that some of the big brands will not sponsor teams this year."

While there is risk attached to celebrity endorsements, some brands are too hasty in dropping stars because of their behaviour, says Mr Abdulkarim. He believes sports personalities should not generally be judged on their private lives.

"Once a brand decides to drop an athlete, for me it is the biggest mistake," he says. "As long as [a celebrity] is perfect in his sport, you should stick with him, because that's why you hired him."

Nike, which unlike some other sponsors did not cast Woods adrift in the wake of his marital infidelities, still benefits from the association, Mr Behrens says. "He is still the [most]-watched golfer in the world. And Nike has been rewarded."

Risk in the endorsement business is inevitable, because celebrities are only human, says John Brash, the founder and chief executive of Brash Brands, an agency based in Dubai.

"It's a great way to get an immediate international impact for your brand," he says. "But the challenge with celebrities is that they're human beings, and act like human beings."