While the Al Bahar towers in Abu Dhabi have received acclaim and accolades as pillars of sustainable design, the project’s lead designer says that they are merely one step towards truly sustainable construction.

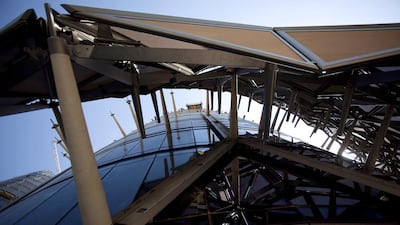

The 25-storey skyscrapers, which serve as the Abu Dhabi Investment Council's (Adic) headquarters, have an external facade composed of 2,000 umbrella-like elements. These follow the sun, closing to block out heat while allowing in light. An array of solar panels on the roof is also utilised to heat water.

However, the towers’ designer, Abdulmajid Karanouh, director of facade design and engineering at the Ramboll engineering group, says an inventive, sustainable shell cannot make up for an old-fashioned, unsustainable core.

“First of all, those two towers are not sustainable towers. They were not designed to be sustainable towers,” he says.

“When I say this, people go mad, they go crazy, they start banging their hands against the table saying: ‘What are you on about? They have won loads of awards based on their sustainable features’.”

His clients wanted a sustainable office building of the western type with concrete blocks, a steel structure and a panoramic glass facade — the “ubiquitous or the mainstream office that you find here in the UAE”, as Mr Karanouh says.

Skyscrapers with glass facades have huge surface areas and absorb great deals of heat — especially in the UAE. “When you’re building in literally one of the sunniest areas of the world, then you start questioning the wisdom behind using fully glassed buildings or facades,” Mr Karanouh says.

This is one of the most significant misunderstandings in construction, he says; there still does not exist a “sustainable” skyscraper — especially not one with a panoramic glass facade. The amount of energy needed to cool, ventilate and light such buildings renders them extremely heavy users of resources.

To make an unsustainable type of skyscraper more energy-efficient, Adic eventually approved a design that wrapped each tower in a veil.

Mr Karanouh says that although people often focus on a façade’s U-value (the insulation characteristics of a material), it is really the G-value (the shading coefficient) that is important.

“When you’re in such an intensely sunny region, in any building, 70 per cent of air conditioning is resulted from direct exposure to solar rays,” he says.

The Al Bahar facade mitigates such heat transfer by 50 per cent, reducing carbon dioxide emissions by 1,750 tonnes a year. The system allows natural light through, reducing the need for artificial lighting. In the end, the true success of the buildings, Mr Karanouh says, is that unlike so many high-rises, they suit the region.

“Even if the mashrabiya [the facade] is closed, you can still see through it. Inside the building, you can barely hear or feel the air conditioning. That means less consumption of fossil fuels. So genuinely addressing a problem lends itself to a more sustainable solution.”

As builders worldwide gravitate towards greater sustainability, their arguments for so doing come not only from ecology but from economics: that the resources you end up saving are, in the end, your own.

“A common issue being discussed around here is cost versus sustainability,” says Saeed Alabbar, the chairman of the Emirates Green Building Council. “There is data around the world, [such as the] research that the World Building Council did with McGraw-Hill Construction, which indicated that there are premiums that sustainable buildings can attract. That’s a large reason why developers are voluntarily going beyond the codes to build more sustainably around the world.”

A thin majority of the McGraw-Hill study’s respondents predicted that 60 per cent of their work would be sustainable by 2015 — a trend driven largely by market demand. Seventy-six per cent said that sustainable construction lowered operating costs and 38 per cent said it raised building values.

The Emirates Green Building Council has a more optimistic outlook on skyscrapers than Mr Karanouh does. “Skyscrapers create high-density environments for living and working in, which facilitates sustainable transport and sustainable urban planning,” says Mr Alabbar. “They create a scale of development which can make things like more energy-efficient technologies, like district cooling, more feasible. So, it’s definitely possible to have skyscrapers which are sustainable and cost-effective.”

Roughly half the council’s 160 representative corporations are manufacturers, and Mr Alabbar says they have a strong commitment to developing sustainable products.

That is sustainability at a grass roots level — if the bits that go in are greener, then so will the building be.

“In the past a lot of the research and development was done in organisational headquarters outside the region, which may not have come up with products and solutions that were region-specific,” says Mr Alabbar. “But we are seeing a lot more R&D being pumped into the region now by suppliers which is, in turn, allowing us to create better buildings.”

One such local manufacturer is Gulf Extrusions, a UAE-based aluminium extrusion company established in 1978. The corporation, part of Al Ghurair Group, produces 60,000 tonnes of aluminium a year.

Arvind Kumar, its business development manager, says the exponential growth of the UAE’s construction industry, and the increasing height and complexity of skyscrapers, is also driving the local manufacturing industry. He estimates that 60 per cent materials used in construction are produced locally.

Dubal, the company’s supplier of raw materials, manufactures more than 1 million tonnes of alumina every year for 300 customers in more than 57 countries worldwide.

Larger buildings mean larger facades, which is where aluminium comes into the picture. Aluminium’s main selling points, Mr Kumar says, are that it is completely recyclable, light, strong, has a high level of thermal comfort and is non-corrosive. Therefore aluminium is well suited to the UAE’s hot and humid summers.

“There’s a lot of impetus, especially from the Government, to shift to green buildings. We have developed green aluminium extrusions and what we’re basically trying to do here is using more post-consumer recycled aluminium — that’s a very important contributing factor to CO2 emissions.

“The Government of Abu Dhabi now have something called Estidama, which is a green rating body which will award points on the green sustainable steps. Some of the skyscrapers coming up are also going for the Leed certification.

“It’s great for us as suppliers because we know how to pitch to the market and we really have an opportunity to educate the end users too.”

Laith Dawood, a project engineer at Al Tayer Stocks, says there is a clear trend towards such genuine innovations, although it will take some time to gain speed. “When I started at university they wouldn’t have had many courses like sustainable design, but now they have these courses inbuilt in universities. Through the generations, people are now becoming more aware of it.”

Mr Dawood says there are a few landmark projects, such as Al Bahar, that do appear to present genuine sustainable solutions. However, he adds these are few and far between — “showcase pieces”. Gradually, though, he says the people who work on these projects will carry forward the sustainable ideas, materials and innovations they encounter on to new projects.

“Everyone will be up to the highest standard at some point. I think it’s definitely a good agenda, but it’s going to take a long time for people to buy into it because they are so set into their own methods of building.”

While the energy efficiency drive is gaining traction in the industry, Mr Karanouh notes that sustainability in construction is not a new idea. “There’s been sustainable buildings in this region for centuries. If you look at historical buildings in the past and the way they were built and the technology that was used, they were trying to do something which was very complex and very sophisticated out of very simple materials and techniques.”

He points out the historical use of domes and wind towers, made predominantly of brick, clay and ceramic, which utilised sophisticated geometry to allow for better ventilation.

The historical mashrabiya windows, on which Al Bahar Towers’ hallmark facades are based, allowed sufficient lighting into buildings without overheating them, he adds. Mr Karanouh believes everything changed during the western colonisation of the region, which brought with it inappropriate construction designs and technologies.

“They were taken completely out of context and imposed on to an alien environment, so you have these buildings which were designed for a certain region, for a certain culture, for certain requirements, and then suddenly you’re placing them in the middle of the desert.

“Research and development costs in the range of millions, but what were spending in this country on importing technologies, materials, cranes and so on is costing trillions — literally. Not billions, trillions.”

He says more context-based research and development is needed to replace the current mentality of adapting ideas from abroad. “If that mentality stays in place, this place will always be a hub for commercial innovation, as opposed to genuine functional innovation.”