Abu Dhabi to Dubai in 12 minutes – it sounds great, right?

It sure does to anyone who has otherwise done the 90-minute drive.

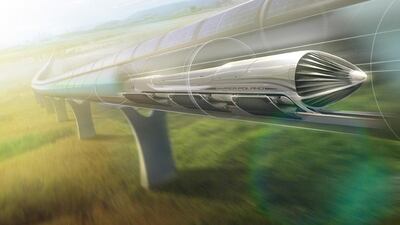

That significant time savings is the golden ring being promised by Virgin Hyperloop One, the California-based company aiming to build a super-fast transport corridor between the two emirates by 2021.

Hyperloop Transportation Technologies, another California-based firm, is also proposing a second line between Abu Dhabi and Al Ain with a total travel time of nine minutes.

It almost sounds too good to be true – and it very well could be if the projects are implemented without taking a holistic approach to the larger potential effects.

The time commuters stand to save by being magnetically propelled in pods through vacuum-sealed tubes at hundreds of kilometres per hour could easily be eaten up by new congestion caused by the very same development.

A recent report in The New York Times noted the paradox stemming from "Marchetti's Constant". Attributed to the Italian physicist Cesare Marchetti, the theory suggests that commuting times generally remain the same over time despite new technological advances in transport methods.

Mr Marchetti has found that, although the average distances that people travel each day have greatly increased over the centuries, the amount of time they spend doing so has remained relatively stable since the Neolithic era.

Rather than taking advantage of technological leaps such as horse-drawn carts, then trains and cars to decrease overall travel times, commuters have simply used the developments to spread out further geographically.

They’ve maintained the same fixed travel-time budget of about an hour per day while cities have grown in size. The result is that many of us take about 30 minutes to drive dozens of kilometres to work. The ancient Romans, however, spent about the same amount of time walking to their jobs.

It’s an open question as to whether that’s real progress or not.

If this historical phenomenon is combined with the UAE’s future projected growth - an estimated population of 10.5 million people by 2030, up 21.9 per cent from 2015, according to Euromonitor - then increased sprawl in major urban centres is all but certain.

Bringing cities closer together will inevitably, and ironically, spread those metropolises further afield internally. Effective distances between large cities may shrink, but travelling around within them is going to take even longer than it currently does, unless other actions are taken. More on this in a minute.

Several studies warn of the downsides of this urban sprawl, including traffic congestion and greater pollution. More importantly, there’s also the potential for greater economic inequality.

______________

Read more:

Branson's Virgin forms partnership with Hyperloop One investment

Latest Hyperloop test video signals Musk's change of mind

______________

A number of cities have in recent years found extravagant inflation in property prices around subway or metro stations, ironically because of commuters’ never-ending quest to cut down on travel times.

A report published last year in Discrete Dynamics in Nature and Society, for example, found a whopping 32-per-cent increase in residential housing prices around newly constructed light rail stations in the Chinese city of Tianjin.

People who can’t afford the more expensive housing end up living further from transit stations and are forced to deal with longer travel times. That contributes to general social unhappiness and fuels resentment.

As Shauna Brail, the director of the urban studies programme at the University of Toronto puts it, the same housing phenomenon is likely to occur with hyperloop stations. “It might be wonderful for the companies that are building the infrastructure and that own the real estate, but really challenging for others,” she says.

It’s a delicate situation, which is why hyperloop development can’t happen in a bubble. The tubes can’t just be plopped down without changes also being implemented to transportation infrastructure within cities themselves.

Fortunately, the UAE appears to be on the right track – pardon the pun – or at least ahead of some other countries that are considering deployments.

Dubai’s ambitious plan to have at least one quarter of all road trips made in autonomous vehicles in 2030 is a good step.

Self-driving cars are expected to significantly alleviate traffic congestion. The more of these cars on the roads, especially working in conjunction with hyperloop pods, the better the chance of improving traffic efficiency.

The two-person Autonomous Air Taxi, supplied by Germany’s Volocopter and being tested in Dubai, is an even more audacious effort to get around traffic congestion.

It’s a fanciful-sounding idea at this point but it could also be precisely the sort of intra-city transportation needed if hyperloop does indeed create more sprawl. The best way to deal with congestion on roads, after all, may be to get above it.

The key to each of these transportation modes, if they do indeed end up becoming reality, will ultimately be their cost – will they be affordable to the average commuter?

Congestion, urban sprawl, property inflation and increased inequality are all potential side effects of installing hyperloop transportation.

As the warning signs indicate, it could end up doing more harm than good if the whole system isn’t usable by the majority of the people.