Western sanctions on Russian crude have boosted sales of old tankers as new companies look to take advantage of high charter rates, according to research firm VesselsValue.

There has been a “significant” rise in the number of tankers sold to undisclosed buyers in both the crude and clean sectors since the fourth quarter of 2022, the firm said in a blog post last week.

Sales of medium-range tankers — the key vessel in the product tanker fleet — rose to 27 in 2022, compared with five a year earlier, VesselsValue said.

“These are players who are looking to take advantage of the premiums available for trading in Russian crude, regardless of the implications that this might have,” it said.

A dirty tanker is a type of vessel that moves unrefined crude oil or other types of dark oils, such as residual fuel oil. A clean product tanker transports refined products such as diesel or petrol.

On December 5, the EU and the Group of Seven advanced economies agreed to place a price cap of $60 a barrel on global purchases of seaborne Russian crude.

This was followed by a price cap on exports of Russian refined products on February 5.

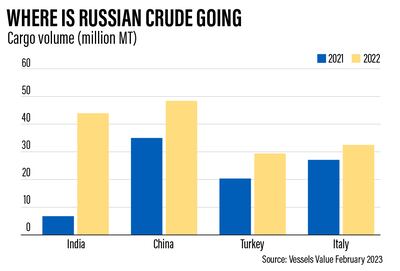

India and China — two of the world’s largest crude importers — have increased their imports of Russian oil since the start of the Ukraine war in February last year.

Russian oil cargoes to India rose to 44 million metric tonnes in 2022, from 6.5 million metric tonnes a year earlier, VesselsValue reported.

China, which was already the largest importer of Russian oil globally, boosted its imports by about 38 per cent to 49 million metric tonnes last year.

Despite the sanctions, Russian oil exports in January rose by 300,000 barrels per day from a month ago to 8.2 million bpd, the International Energy Agency reported.

Meanwhile, the country’s export revenue stood at $13 billion, slightly higher than in December, but down 36 per cent from the same period a year ago.

“With export levels relatively unchanged, it is debatable if sanctions are having any meaningful economic impact on Russia,” said VesselsValue.

“There are reports that Russian crude is being refined in places such as China, and then being sold back to EU countries as clean petroleum products.”

Russia, the world’s second-largest oil exporter after Saudi Arabia, has said that it would cut production by 500,000 bpd, or about 5 per cent of the output, in March.

“If the sanctions remain in place, we expect the ‘dark fleet’ will continue to operate for the foreseeable future,” said VesselsValue.

“With fewer tankers available, tighter tonnage supply, combined with changes to trade flow patterns for Russian oil and refined products, there should be support for both crude and clean rates in the future.”

Rates for transporting crude oil via tankers have surged to levels not seen since 2008, except for a short period in 2020, when oil companies urgently sought tankers to stockpile fuel because of the pandemic-induced demand drop.

This month, the International Energy Agency raised its 2023 global oil demand estimates as China reopened its economy after about three years of adhering to a strict zero-Covid policy.

Global oil demand will rise by two million bpd to 101.9 million bpd this year, said the agency, which had forecast a growth of 1.9 million bpd in January.