Indian farmers in their thousands from across India marched towards New Delhi in protest earlier this month.

Some of them made the journey riding their tractors, while others went on foot, as part of a march that began about 200 kilometres away in Haridwar. The farmers' protests were met with water cannons and tear gas at border between Delhi and Uttar Pradesh, where they were stopped by police.

Their list of demands was long, including unconditional waivers on their loans, higher prices for crops and cheaper fuel and electricity bills. In response, the Narendra Modi government did agree to look at many of their demands, and raised the minimum support price for certain crops – the rate at which the government buys crops from farmers, to protect producers from sharp falls in prices.

With India heading towards a general election next year, due by May, farmers' problems are becoming a political issue, given the number of their votes.

But farmers and analysts say many of the issues remain unresolved, as farmers continue to face financial challenges as they grapple with higher costs and try to turn a profit, with soaring fuel and fertiliser costs adding to their woes.

“Everything boils down to finance and economics,” says Ravi Chandran, a third-generation farmer based in the state of Tamil Nadu in south India. “The income generated from farming is not adequate enough to take care of even our basic needs.”

Farming is a a critical part of the country's economy. India's agriculture sector makes up 16 per cent of the country's economy, while accounting for 49 per cent of employment, according to India's Economic Survey, a government document. Most of India's 1.3 billion population live in rural areas.

But many farmers in India are saddled with debts that they are unable to repay, leading to rising numbers of them committing suicide in recent years.

The obstacles only seem to be mounting. Fuel prices in India have soared to record highs, with diesel prices rising about 25 per cent this year, driven by higher crude prices and the weak rupee, which has tumbled to record lows, making oil imports more expensive. It has been hard for farmers to get decent prices for their crops amid high output. This comes alongside other deep-rooted challenges.

“On account of multiple factors, farmers continue to struggle,” says Abhishek Bansal, the chairman of ABans Group of Companies, a financial services firm based in Mumbai. “These include small land holdings, lack of organised credit, exploitation by middlemen and over-dependence on the monsoons.”

He says the majority of land holdings of farmers in India are small plots, which are “unviable” and “deprive the farming sector of the numerous benefits of large-scale farming”. It is particularly hard for these small-scale farmers to manage rising costs.

There are other elements that are adding to the pressure on Mr Modi's government, which came to power in 2014, partly helped by farmers' votes, and has made an ambitious promise of doubling farmers' incomes by 2022.

The monsoon is another uncertainty farmers face every year in India, with their crop production being heavily dependent on the rains. The country depends on the south-west monsoon - which lasts from June to September - for 70 per cent of its annual rainfall.

Although the overall amount of rainfall in the country was considered “normal” this year, 21 per cent of India was left moderately to extremely dry, according to the India Meteorological Department, which is leading to concerns about drought.

“There are some spoilers. Rainfall distribution has been patchy and farmer incomes are down,” says Dharmakirti Joshi, the chief economist at Crisil, a ratings and research firm headquartered in Mumbai, which is part of Standard & Poor's.

Prakash Sambhaji Alinje, who owns farmland in Nashik in the state of Maharashtra in western India where he grows crops including rice and wheat, thinks the rainfall has been adequate this year but that, in general, water is major area of concern.

“Increasing competition for water between industry, domestic use, and agriculture has been another major drawback for the farmers,” he says.

His main worries at the moment are rising costs and the fact that even if crop production is good, it can be difficult to sell produce and get the right price.

_______________

Read more:

India did not put people first in demonetisation of 2016

Monsoon festival brings bull racing to India's paddy fields - in pictures

_______________

"We are strained to use the large amounts of costlier fertilisers and pesticides for higher yield, but sometimes the seed does not give the claimed yield and run into economic trouble," says Mr Alinje. "The lack of proper marketing channel" and with no central or formal system to sell their goods or compare prices, means farmers can't get the best prices for their produce, "which makes it beneficial for the greedy middleman and ultimately restricts our income".

Although the government has introduced minimum support prices for some crops, this does not apply to all crops and, in reality, this initiative has shortcomings, industry insiders say.

“The whole issue around farmers is a vicious circle,” says Pankaj Agarwal, the co-founder and managing director of Just Organik, an organic products company in India. “Farmers get into the challenge of arranging for the inputs for their agriculture, then getting the crop yield, and trying to sell. The government has started increasing the minimum support price for farmers, but most of the time these farmers are still forced to sell their food at a nominal price because they are in the dire need of the cash to pay off their debts that they have taken to buy the inputs to produce the crop.”

Some state governments, such as Maharashtra, also resorted to loan waivers over the past couple of years, which is seen as a populist move to try to win votes, and a costly one given the burden it places on state funds. The opposition Congress party is also playing this card. With state elections coming up in Madhya Pradesh, the party's president Rahul Gandhi has promised to waive farmers' debts if Congress is voted into power in the state.

These funds could be much better spent on educating farmers as a longer-term solution, says Mr Alinje.

“If the farmers are made familiar with the basic principles of agronomy or the prevailing market we can see some good results,” he says.

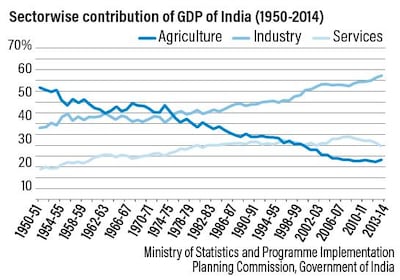

Suman Chowdhury, the ratings president at Acuité Ratings and Research, based in Mumbai, says it is not surprising that agriculture is contributing a declining share of GDP in India, as the services and industry sectors continue to grow at a much faster pace.

“As a country develops and goes on from a developing to a developed economy, we will see a lower share of agriculture,” he says, although he adds: “I wouldn't say that there's a crisis at this moment.”

What is needed to help agriculture is improved infrastructure and a robust national pricing system so they can demand better rates for their crops, he says.

The fact that farmers' struggles are increasingly becoming a political issue is only distracting authorities from addressing the issue properly, some of those affected argue.

“When there is a problem, there should be a solution,” Mr Chandran says. “Instead of indulging in blame games, the policymakers must critically evaluate the underlying problem. No one should politicise farmers' issues.”

But he adds that the financial troubles of farmers in India are such that he sees no easy solution in the rapidly modernising country.

“Technology, market facilities, financial support, subsidies and incentives, insurance, though playing a crucial role, the problem is more than what meets the eye,” he says.

“The situation will deteriorate further if the core issue of farming is attended to immediately.”