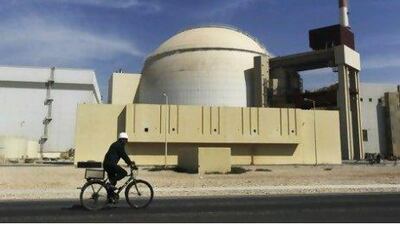

Started by German engineers in 1975, bombed during the Iran-Iraq war, restarted by the Russians in 1995 in the face of US pressure to stop, and finally cobbled together from leftover components, Iran's Bushehr nuclear plant, which began operating in September, is a strange beast.

Sited astride an earthquake zone, and closer to all the GCC capital cities than to Tehran, Bushehr is not the way to launch nuclear power in the Middle East.

The UAE's civil nuclear power programme is entirely different. It has an independent regulator and an international advisory board that includes Hans Blix,renowned from his days hunting for Saddam Hussein's weapons of mass destruction.

The Emirates chose to forego domestic uranium enrichment and reprocessing to allay concerns of nuclear weapons proliferation. Lady Barbara Judge, the chairman of the UK Atomic Energy Authority, said, "If I was going to write a template on how to begin a new nuclear programme and to get the world behind you instead of against you, I would say Abu Dhabi is doing it exactly the right way. It's best practice multiplied by three."

The imperative of soaring domestic energy demand is driving other Middle East countries to think nuclear, although in the wake of Japan's Fukushima accident a year ago, Kuwait announced last month it was abandoning its atomic energy plans.

But permission was given on Thursday for site preparation to begin on the first two out of four reactors planned at Braka in Abu Dhabi's Al Gharbia region.

Saudi Arabia plans to spend more than US$100 billion (Dh367.31bn) on 16 nuclear reactors over the next two decades and use its oil for exports.

Jordan, its economy hamstrung by high energy bills and repeated attacks on its gas pipeline, is also moving ahead with nuclear plans.

There are good reasons why the Middle East and North Africa (Mena) countries can enjoy part of the global "nuclear renaissance", albeit a more halting and fragmented renaissance than seemed likely before Fukushima.

Capital is readily available, at least in the Gulf, land is abundant and planning procedures relatively speedy. Public support is strong, certainly far more than in the US or Europe, with 85 per cent of UAE residents surveyed believing nuclear power is important for the country.

The key is building the right regulatory systems. Even in an advanced industrial democracy such as Japan, the Japanese "nuclear village" featured far too cosy a relationship between the industry and those overseeing it.

Mena countries have a long road ahead in developing the nuclear expertise needed to run the plants. Water, required for cooling and in emergencies, may not be easily available, in particular in Jordan with its short coastline. More interconnections are needed to allow countries to share electricity in the event of unplanned shutdowns.

Nuclear power is preferable to burning oil for electricity when the price exceeds US$60 to $70 per barrel, well below current levels. There is the tantalising prospect of using nuclear power, with its copious quantities of waste heat, for desalination - successfully demonstrated in Japan, India and Kazakhstan.

A triptych of nuclear for steady year-round demand, solar power to meet midday air conditioning, and gas for the evenings can be the foundation for a Middle East future of abundant, affordable and low-carbon electricity.

But this can only be achieved if all the region's nuclear users make a leap forward on competence, safety and transparency.

Robin Mills is head of consulting at Manaar Energy, and author of The Myth of the Oil Crisis and Capturing Carbon