Millions of pilgrims from around the globe will converge on the holy city of Mecca in the coming days for the pilgrimage of the Haj, the world's most diverse gathering. Last year some 2.8 million Muslims from 181 countries made the voyage to Saudi Arabia. It's a crowded, emotionally intense, physically challenging and spiritually demanding experience.

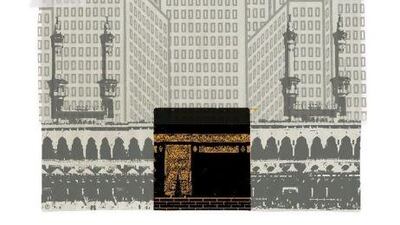

Arriving at the Kaaba, the pilgrims fall to their knees weeping. Since they first performed their daily prayers as children they have faced towards it in worship. Their dreams of Mecca are powered by wishes to step on the sand that has seen the footsteps of the Prophet, to feel the wind that has overseen the revelation of the Quran, to be where the promise of Islam was delivered. To be in this most blessed of places, they may have saved painstakingly over decades. And finally, here they are at the doors of the House of God.

Geography and history have laid the mantle of responsibility on the shoulders of Saudi Arabia, within whose borders lie the holy cities of Mecca and Medina known together as the "haramain" and from which the king of Saudi Arabia draws his title, "Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques". The honorific brings with it a heady responsibility. Modernisation and the age of the jet plane have multiplied the thousands of pilgrims who once embarked upon the road to the Haj into millions.

To accommodate the pilgrims, there are ambitious plans for the expansion of the areas around the haramain, flattening almost the entire surroundings to construct multiple high rise luxury hotels, shopping centres, and access roads.

It's easy to criticise the Saudi authorities for these plans but pilgrim management is a challenging task. Muslims want to go to Mecca, and rightly so. But on arrival, they complain if facilities are not good enough, if hotels are not near enough, if paths are too crowded, if travel is too slow. Visitor numbers are rising annually, and quotas are deeply unpopular. With 1.8 billion Muslims in the world - and growing - conditions are unlikely to improve in the near future.

Improvement efforts are continuous. The building around the Kaaba is multi-storeyed to increase capacity. Last year, a monorail was built to transport 70,000 pilgrims an hour. This year, pilgrims will be issued with digital smart cards to make the processing of visitors faster and smoother.

Expansion will allow Saudi Arabia to increase the number of pilgrims. Muslims will benefit through greater access and the country will increase its tourism revenue. In 2009, 12 million pilgrims brought in US$7 billion. By 2013 the goal is $15bn. Last month the chair of the Tourism and Antiquities Commission talked about tourism as a way of generating income, relieving poverty, and creating jobs. There is talk of an "Umrah Plus" programme to open up travel for Umrah visitors, who currently are not permitted to venture outside the holy cities. The commission speaks of sites such as the ancient Nabataean city in Madaen Saleh and the 300-year-old village of Rijal Alma. It is heartening to see that the Saudi authorities are realising the value of their heritage.

This is not the case for sites of Islamic religious historic importance say detractors. They point to news stories about sites in the vicinity of the haramain being bulldozed in minutes. These precious morsels of Islamic heritage will be replaced by towering luxury hotels. No wonder the global media has likened Mecca to Las Vegas.

The sites date from the time of the Prophet, his companions and the early Islamic empire. Experts say some even date back to the time of Abraham. The Quran repeatedly exhorts believers to "travel the world" and "see the fate of those who have gone before". The implicit conclusion from this is that there is a religious duty on believers to preserve historical remains.

The bad news, say critics, is that so many important sites have been destroyed that only 20 or so remain from the period of the Prophet. An example is the graveyard of Jannatul Baqi in Medina, which contains the graves of the Prophet's companions, his daughter Fatima, his wife Khadija and his grandson Hassan. It was bombed in 1926 to make the earth flat and undistinguished, all markings of these key individuals gone forever. Another site is the birthplace of the Prophet himself, which has been hidden beneath a library.

Saudi Arabia is a powerful member of, as well as the headquarters of, the Organisation of the Islamic Conference, whose 57 members represent the majority-Muslim nations of the world. It was founded in 1969 in response to an arson attack against the Al Aqsa mosque.

The OIC continues to object vociferously to the destruction of Islamic sites in Israel. At its December 2005 meeting in Mecca, the preservation of historic Islamic sites in Jerusalem including the Al Aqsa mosque was raised as an issue of grave concern. Documents talk of steps to "safeguard the city's cultural and historic landmarks and Arab-Islamic identity".

The secretary general Ekmeleddin Ihsanoglu warned of "illegal Israeli practices" and "aggressions" that aim to alter "historic landmarks". He wrote elsewhere that the OIC should "spare no effort to preserve the Islamic historical and religious identity of Al Quds Al Sharif".

In response to calls to preserve Islamic heritage sites, the Saudi religious authorities say that their destruction is to avoid shrine-worship. The Haj authorities say it is to accommodate the ever growing numbers of pilgrims.

But the Muslim world says that it wishes to see its religious and cultural heritage preserved. I say that Saudi Arabia has a religious duty - which nobody denies is a challenging one - to balance the needs of pilgrims with the need of the ummah to retain its history. For many, historic sites are a key part of the pilgrimage experience. It may be at odds with the purist Saudi Salafi tradition, but these actions are accepted within the wider Muslim heterodoxy.

Saudi Arabia needs to be cautious about giving the impression that it does not care what the global Muslim community feels - even if that differs from its own specific tradition. The more damaging impression is that it cares more about commercialisation and less about historical legacy.

Saudi Arabia also needs to ensure that the increasing cost of pilgrimage avoids pricing out the majority of the Muslim population. Even if pilgrims can scrape pennies together and use one of the low-cost Haj agencies the authorities have licensed, the "premium" focus of the tourism industry will affect the Haj experience in a profound way.

Consider that in the immediate proximity of the holy sites all the accommodation will be in luxury hotels. Only the rich will stay there, the poor shunted out of view. Haj will become a two tier experience, in opposition to its ethos of creating equality between rich and poor.

Saudi Arabia bears a heavy responsibility for the care of pilgrims and a religious duty mandated in the Quran to preserve historic religious sites. And we must not forget the responsibility of maintaining the egalitarian ethos of the Haj itself. If it can achieve all of these, then it will win the hearts of the world's Muslim population, and do justice to the pinnacle of Islamic rituals.

Shelina Zahra Janmohamed is the author of Love in a Headscarf and writes a blog at www.spirit21.co.uk

Steps Saudi Arabia needs to take to enhance the Haj

Saudi Arabia has a religious duty – which nobody denies is a challenging one – to balance the needs of pilgrims with the need of the ummah to retain its history.

Most popular today