The award-winning director of Muhammad, the most expensive movie in the history of Iranian cinema, says he hopes it will improve the "violent image" of Islam.

However, the religious epic, about the childhood of the Prophet Mohammed, runs the risk of angering some Muslims, even though it does not depict his face on screen.

The ambitious production cost an estimated US$40million (Dh147m) and took more than seven years to complete. The 171-minute film, which stars many leading Iranian actors, will premiere on August 27 in 143 cinemas in Iran, the same day it opens at the Montreal Film Festival. The film was supposed to open in Tehran on Wednesday August 26 but was postponed for 24 hours due to technical problems, a spokesman said.

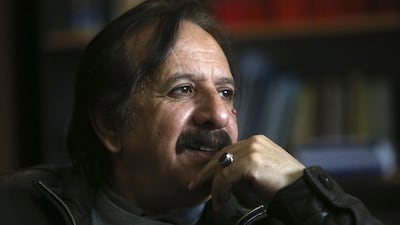

Speaking in Tehran, director Majid Majidi, 56, says extremists such as the Islamic State “have stolen the name of Islam”. In the Western world, “an incorrect interpretation of Islam has emerged that shows a violent image of Islam, and we believe it has no link whatsoever” to the religion, he adds.

Muhammad, which was partly state-funded, is the first part of a planned trilogy about the life of the Prophet. The film depicts events before his birth and up to his teenage years.

While many screenings in Shiite-majority Iran have already sold out, in the Sunni Muslim world the production has proved more controversial.

“Definitely, some countries, like Saudi Arabia, will have problems with this film but many Islamic countries – including Turkey, Indonesia, Malaysia and many others in Southeast Asia – have asked for the film,” says Majidi, who has won international prizes, including the Oecumenical Special Award in Montreal, for promoting unity among religions.

The first major production about the life of the Prophet, Syrian-American filmmaker Moustapha Akkad's Mohammad, Messenger of God also drew criticism in the Muslim world when it was released in 1976.

In an attempt to allay concerns, Majidi looked for alternative ways of depicting the Prophet, and chose not to show his face at all.

"To have the hero throughout the movie and not show his face once is a big challenge," says Majidi, whose film Children of Heaven was nominated for Best Foreign Language Film at the Academy Awards in 1998.

He and his Italian Oscar-winning cinematographer, Vittorio Storaro, came up with a special technique to get around the problem.

“We customised a steadicam especially for the Prophet,” he says. “Wherever we have the Prophet in the film, we see through his POV [point of view], even in his childhood.

“Everyone is curious to see the Prophet in the film, but you cannot see his face,” he says, adding that the Prophet is only seen by his profile, or with his back to the camera.

Still, his solution is not enough for experts at Al-Azhar, a leading Sunni Muslim institution in Egypt.

It says it “objected to portraying prophets and messengers in art” as it is “tantamount to belittling their spiritual status”.

It opposes not only portraying the prophets’ faces but also their voices.

“The actor who plays this role may later play a criminal, and viewers may associate these characters with criminality,” says Abdel Dayyem Nosair, adviser to Al-Azhar head Ahmed al-Tayyeb.

artslife@thenational.ae