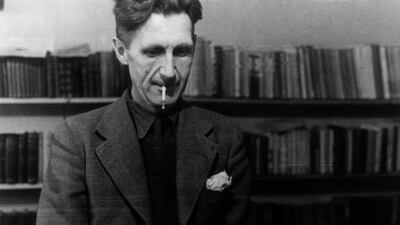

Like some 70s rock group with a large and miscellaneous back catalogue, George Orwell has been subjected to a merciless programme of repackaging over the past few years.

A glance along the bookshelves reveals half-a-dozen of these stout compilations – Orwell in Tribune (the left-wing weekly magazine where he spent two years as literary editor); Orwell: The Observer Years; Orwell's Diaries; George Orwell: A Life in Letters; Orwell's England – all of them pieced together from the 11 books of essays, letters and journalism included in Professor Peter Davison's magisterial 20-volume The Complete Works of George Orwell (1998). If there are still biographers and critics romantically "in pursuit" of the author of Nineteen Eighty-Four, then, with this miniature library to hand, they certainly know where to find him.

Not that there is anything in the least exploitative about this torrent of recycling. Like W M Thackeray and George Gissing, the two Victorian novelists in whose steps he may be said to have trodden, Orwell’s output was prolific to the point of mania. Quite apart from the six novels and three books of reportage, his 21-year career as a published writer (1928-1949) realised nearly 4,000 pages of print.

In his foreword to the current selection, Davison estimates the volume of work Orwell produced 330,000 words between July 1943 and December 1945 – a total that becomes even more implausible when you consider that it ran alongside the Tribune job. Six-and-a-half decades after his death, of pulmonary tuberculosis at the age of 46, his legacy takes the form of an outsize bran-tub, into which – Orwell being Orwell – repeated dips bring up anything but bran.

Davison, now in his late 80s, has grown grey in the service of Orwell Studies, but Seeing Things As They Are is one of his best efforts yet – possibly the best of all, for it succeeds in demonstrating quite how important hackwork was to Orwell's sense of his professional identity. If nothing else, this was a career haunted by deadlines, by the obligation to review parcels of second-rate novels at a few days' notice, to file weekly columns (see in particular As I Please which ran in Tribune from 1943 to 1947), to attend – at any rate briefly, in the early 1940s – film previews and theatrical first nights. Even in the immediate post-war era, hard at work on the early drafts of Nineteen Eighty-Four, he described himself as "smothered under journalism", and the last typescript printed here – an unfinished essay on Evelyn Waugh – was written while lying in a sanatorium bed.

The type of literary work that critics tend to mark down as "casual writing" – articles written in great haste on sometimes ephemeral topics – rarely survives beyond the moment in which it was written. What makes Orwell's so important? At one level the kind of reviews and essays he was writing for publications as various as Horizon, the wartime monthly edited by his friend Cyril Connolly, or shoestring weeklies such as Time and Tide, are a testimony to the breadth of his interests. The existence of poltergeists; the rudeness of shopkeepers; the Woolworth's roses that he grew in the garden of his Hertfordshire cottage; the history of the detective story – all these are discussed with exactly the same seriousness that he brings to the flying bomb, the need for penal reform or the Nuremberg hangings.

At the same time, Seeing Things As They Are is full of dry runs, and the first stirrings of ideas that would be treated at greater length elsewhere. From the vantage point of Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), for example, one of the most prescient book reviews Orwell ever wrote was a Blitz-era round-up of four dystopian novels (Jack London's The Iron Heel, H G Wells's When the Sleeper Awakes, Aldous Huxley's Brave New World and Ernest Bramah's The Secret of the League) – a kind of parading of some of the influences that would help create his own vision of the totalitarian future. The same prefigurative effect is produced by a Tribune piece from 1944 in which, considering the decline in religious belief in western Europe, Orwell notes that "there is little doubt that the modern cult of power worship is bound up with the modern man's feeling that life here and now is the only life there is".

There can be no worthwhile picture of the future, he goes on, "unless one realises how much we have lost by the decay of Christianity". Instantly we are fast-forwarded to the world of Big Brother, where leaders are judged by material success, happiness is measured in cigarettes and bottles of Victory gin, tyranny can never be checked by the thought of the celestial judgement seat, and it becomes that much harder to believe that you are in the right even if you are defeated. If there is no God, Orwell seems to be saying, then we can do what we like with impunity. One of Nineteen Eighty-Four's subtexts, consequently, is the need to devise a secular morality that encourages the average man to behave decently and cling to the moral teachings of Christianity without threatening him with eternal hellfire or promising him a seat at the table in paradise.

Orwell's 1940s journalism is full of these early warning systems, flashing lights that wink up from the page to offer advance notice of the direction in which his mind is travelling. Practised Orwell-sleuths will spot another Tribune piece from early 1945 in which he suggests that "quite visibly and more or less with the acquiescence of all of us", the world is splitting up into "two or three huge super-states … One cannot draw their exact boundaries as yet, but one can see more or less what areas they will comprise" – exactly the geographical premise on which Nineteen Eighty-Four is based. It would be overstating the case to argue that Orwell foresaw the onset of the Cold War and the four-and-a-half decades of East-West stand-off that followed, but many of his predictions of the likely state of late 20th-century continental Europe turned out to be horribly accurate.

Not everything here is divination, for Davison is so keen to ransack the various compartments of his subject's life that he goes as far back as the poem Awake! Young Men of England, which the 11-year-old Eric Blair – to give Orwell his baptismal name – contributed to The Henley & South Oxfordshire Standard in October 1914 and as far forward as Orwell's funeral in January 1950, remembered by his publisher, Fred Warburg, as "one of the most melancholy occasions of my life". In between, there are countless examples of one of Orwell's most attractive qualities, his interest in things and people for their own sake, and his capacity to wrest a wider significance – and at the same time a personal resonance – out of the most mundane material.

Take, for example, an extract from the As I Please column of 26 May, 1944, written a week before the Normandy Landings that ushered in the final phase of the Second World War. Here Orwell runs his eye over a publication called The Matrimonial Post and Fashionable Marriage Advertiser – the modern equivalent would be a dating website. He remarks how eligible most of the candidates are ("When you consider how fatally easy it is to get married, you would not imagine that a 36-year-old bachelor, 'dark hair, fair complexion, slim build, height 6ft., well-educated and of considerate, jolly and intelligent disposition, income £1,000 per year and capital', would need to find himself a bride through the columns of a newspaper") and then moves on in search of the wider social tendencies beyond the individual case.

What the advertisements really demonstrate, he decides, is the “atrocious loneliness” of people who live in big population centres. The column concludes with an anecdote about a woman with whom he lodged in West London in the late 1920s whose sense of her social position forbade her to borrow a ladder from the jobbing builder who lived next door on the grounds that “it wouldn’t do”. It is an intensely Orwellian moment, sparked by a fragment of social detail, ending with a brisk little parable of the way in which bygone English society worked, in which Orwell himself is deeply involved, fascinated by its implications, and, as ever, half in love with the very things he is arguing against.

D J Taylor is a novelist and critic whose journalism appears in The Independent on Sunday and The Guardian.