From Croatia to China, and across the Middle East, people have long been entertained by the misadventures of Molla Nasreddin, the folkloric figure of the Sufi wise man-cum-fool who is often depicted riding backwards on a donkey. As Payam Sharifi, the co-founder of the art collective Slavs & Tatars, tells me, it’s appropriate that Nasreddin shares his name with an incendiary early 20th-century satirical magazine that is also the subject of his public lecture at the NYUAD Institute on January 27.

Mainly published in Azerbaijan between 1906 and 1931, the weekly eight-page magazine was widely read across the Muslim world. It caused widespread outrage by attacking hypocrisy in the Muslim clergy and the damage done by colonialisation as well as local corruption, while making a convincing case for westernisation, educational reforms and women’s rights.

Sharifi will give the talk as Slavs & Tatars, the art collective that began life as a book club seven years ago; it has since published six books including Molla Nasreddin: The Magazine That Would've, Could've, Should've in 2011. Now out of print, the book contains 200 illustrations out of the thousands that appeared during the magazine's lifetime, but while Slavs & Tatars embraces the magazine as a cultural artefact, its perspective is highly critical. "It's an incredibly important historical document," Sharifi says, "but we as Slavs & Tatars actually disagree with a lot of it … And the reason we disagree is that it is a product of its time. These editors at the time believed that modernisation had to go to westernisation. We don't believe that.

“That is part of the reason Slavs & Tatars was created, to think about different thought processes, different belief systems that offer a legitimate counterweight to that very idea.”

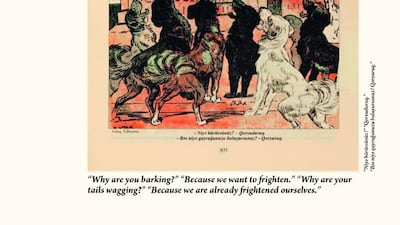

Flicking through the pages of Molla Nasreddin: The Magazine That Would've, Could've, Should've, the reader is confronted with extraordinary cartoons that a century later still have the capacity to shock, even though Slavs & Tatars was careful in its choice of images. Sharifi admits that fear of trouble influenced the decision not to cause offence, but it would be more accurate, he says, to attribute their edit to a wish to encourage broad debate.

“There might have been a time in the early 20th century up until 30 or 40 years ago, the idea that critique had to be done in a confrontational, aggressive manner.

“We actually believe that we are living in a different world. I often say that the best way that you can deliver critique is when you invite your enemy to the table and you break bread with him.

“People don’t want to be spoken at, they want to be spoken to.”

The editors of the magazine took the opposite view and lived in hiding. Looking at some of the cartoons you can see why: in one, a fully veiled woman cowers from a doctor, refusing her husband’s pleas to let him examine her throat, but then lies back unclothed to allow a cleric to wield an ink brush. The caption reads: “Let the mollah write a prayer around my belly button. It can’t do any harm.”

Inevitably the subject of the terrorist attack on Charlie Hebdo, the Paris-based satirical magazine that published cartoons of the Prophet Mohammed, comes into our conversation. Is a comparison between Molla Nasreddin and Charlie Hebdo helpful or even relevant?

"It is useful in so far as it violently brushes these issues out from under the carpet, the proverbial Persian rug," Sharifi says. "[But] if you were going to look at Molla Nasreddin as a scholar and ask is this in the tradition of Charlie Hebdo? It definitely comes from another French tradition, which is an anarchist publication called L'assiette au beurre."

There's no doubt, however, that the savage assault on the French magazine's offices gives Molla Nasreddin a new relevance. "I don't want to focus on Charlie Hebdo too much," Sharifi says. "But one thing I read that I thought was very apt which somebody wrote was that they had never seen a cartoon about Mohammed that actually made them laugh. And I had never thought about it but it is true, if it were funny I could excuse a lot.

“For us the real reason we are interested in both the magazine and the figure of Molla Nasreddin is that humour is a really interesting and complex and effective way to deliver commentary – critique – and there is a particular kind of humour, in contrast to what has recently happened, that is generous. It laughs at itself as opposed to at people.

“It is easy to keep putting your finger in someone’s eye but what is much harder is a humour that is inclusive and I think what we are faced with increasingly is a need for mutually inclusive discourses and not mutually exclusive ones.”

• The public talk Satire in the Muslim World: Molla Nasreddin takes place on January 27 from 6.30pm at the NYUAD Institute. Translation in Arabic available. Register at nyuad.nyu.edu.

Clare Dight is the editor of The Review.