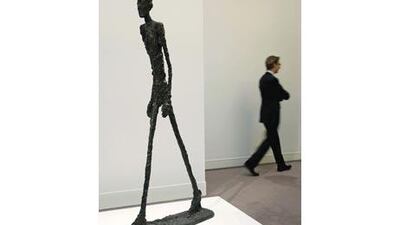

Forget property price rises and the return of bankers' bonuses; a clear sign that the global economic downturn may finally be drawing to an end came last week with the resounding thwack of an auctioneer's hammer. These belt-tightening times were shaken up on Wednesday with the world-record breaking £65 million (Dh383m) sale of Alberto Giacometti's sculpture L'Homme Qui Marche I at Sotheby's in London.

Or at least, that was the popular view. It rather overlooked the fact that, ironically, this work of art was actually an asset of a German financial institution, Dresdner Bank, which had sunk so low it had to be bought out during the credit crunch. Nevertheless, somebody was solvent enough to consider paying five times the initial asking price of £12m for this etiolated bronze figure. The identity of the "somebody" in question remains elusive, but it is an oddity of the sale that even £65m does not buy you exclusivity.

The Swiss sculptor created L'Homme Qui Marche in 1960, and when he had it cast it a year later, he did so in an edition of six figures. So you can see exactly the same sculpture at museums in Pittsburgh, Buffalo and Louisiana in the United States, Saint-Paul in south-east France and Hornbaek in Denmark. So why the astronomic price? Why is a sculpture by a relatively unknown artist worth more than the previous record-holder, Pablo Picasso's Garçon à la Pipe?

The man in the street might nod in recognition at a Monet, a Klimt, a Van Gogh, a Renoir, a Rothko - all at various points the most expensive artworks to go under the hammer. But, until this week, a Giacometti? It appears rather doubtful. The reason, perhaps, lies in what L'Homme Qui Marche represents. It was cast during the Cold War, and many art scholars have linked Giacometti's figures with a worrying vision of humanity, post-nuclear war.

But this sculpture - as any truly great artwork must - resonates across the decades and centuries. It is instantly reminiscent of the ashen corpses at Pompeii, and horrifically recalls the emaciated prisoners of Second World War concentration camps. Certainly, too, Giacometti was fortunate in that he earned the patronage of the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, who often said that the piece represented a pessimistic existentialist view of the world's future.

If all that sounds impossibly dark, Giacometti himself said he viewed his striding figure as a symbol of man's own life force - and there is a genuinely uplifting feel to L'Homme Qui Marche. In walking forwards, the sculpture seems to say that life goes on, despite the torments of existence, and in a way, Giacometti's spindly figure is the human spirit boiled down to its real, emotional heart. It is like Cormac McCarthy's novel The Road in bronze.

In a sense, Giacometti's work has become a cipher for our times. Garçon à la Pipe was sold in 2004 for $104.2m (Dh382.7m), but art critics are hugely divided about whether, without Picasso's name on the bottom, it would be a particularly interesting painting. In essence, it is a portrait of a boy with some flowers on his head. L'Homme Qui Marche, though, has a wider significance. It is an important work that has a direct relevance to the 21st-century experience, whereas Garçon à la Pipe is a very distinct snapshot of Parisian life early in the 20th century.

Of course, owning a record-breaking artwork is also a status symbol, with all the attendant bragging rights for the successful bidder. You sense that the real reason L'Homme Qui Marche ended up selling for such a ridiculously high price was not simply thanks to the cachet of the artist's name, or even what the piece looked like or meant. It was, perhaps, because the competing bidders enjoyed the thrill of the battle in the searing heat of the auction room. It is worth noting that another Giacometti bust up for auction that same night in Sotheby's failed to sell at all.

Such are the vagaries of the art world. One thing is for sure, the new owners of Dresdner Bank would be well advised to complete the sale as soon as possible. Four years ago, Steven Cohen tried to make the most expensive art purchase in history when he offered $139m to the casino entrepreneur Steve Wynn for Picasso's La Rêve. The deal was done- and just days before Cohen was expecting to take delivery of his new pride and joy, Wynn accidentally put his elbow through the canvas, ruining the painting.

Let's hope Giacometti's quote - "All the sculptures of today, like those of the past, will end one day in pieces-" - is not imminently prophetic.