Opinion: With close to 100 accusations against him, Harvey Weinstein's conviction as a sex offender should have been a foregone conclusion. Weinstein may be #MeToo's most high-profile, notorious, and perhaps universally loathed case, but there was still the lingering feeling that he may not actually be found guilty. But he was – of criminal sexual assault in the first degree and third-degree rape.

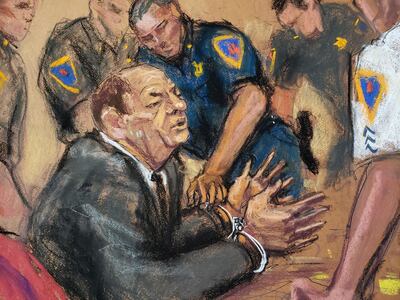

The man himself appeared stunned: he was photographed walking into court looking self-assured, even as the jury went into its fifth day of deliberations, but was seen walking out of it dazed, dragging his feet, and muttering repeatedly, “but I’m innocent,” and “how can this happen in America?”

Really, should we be celebrating the fact Weinstein now faces anywhere between five and 29 years in prison for committing a criminal sexual act in the first degree and third-degree rape? Or should we be mourning that after about 30 hours of deliberation, the jury decided to let Weinstein off the most serious charge of the three – predatory sexual assault?

What does it mean for a judicial system and a society, when close to 100 accusers boil down to only three charges that stick, of which only two result in conviction? I don't know how anyone even vaguely familiar with the particulars of his case could harbour doubt of his guilt, given that almost 100 women have shared harrowingly similar accounts.

If Weinstein is innocent, he certainly has a funny way of showing it. There is documented evidence of financial settlements that his extensive legal team have brokered on his behalf with women who have tried to come forward with their stories. It's a matter of public record that Weinstein had Kroll, one of the largest corporate-intelligence companies in the world, and Black Cube, a company run largely by former Mossad officers and operatives from other Israeli intelligence agencies, on his payroll to gather information on accusers and reporters. Those are some extreme, not to mention expensive, pre-emptive measures to avoid litigation by someone who believes himself to be innocent.

Two convictions after decades of abuse and hundreds of graphic details that have worked their way into the public domain should not feel like a victory, but they are, given the history of Hollywood and other industries where women have learnt to deal with sexual harassment as a particularly grotesque form of paying their dues.

At the age of 67, and with failing health, the length of Weinstein's sentence or the exact nature of the charges he has been found guilty of don't matter quite as much as that in convicting him, America has recognised – as the world watches and takes note – the messiness of sexual abuse allegations, especially when the power imbalance between the accuser and the accused is as monumental as between Weinstein and his accusers.

Weinstein's conviction is a watershed moment for #MeToo, not only in Hollywood or the US, but around the world, because even his country's law is acknowledging that it is entirely possible for rape and criminal sexual acts to have occurred between people who continue to remain acquaintances after the incident.

Perhaps one of the reasons for Weinstein and his legal team's almost preternatural calm prior to the verdict was that they had managed to prove that all the women accusing him in court had continued to be friends with him, some even maintaining relationships with him. At the heart of their legal strategy was the assertion that it was Weinstein, not the women, who was the real victim, suffering a career-destroying fallout from a social justice movement that has "gone too far". Weinstein's lawyers have dutifully parroted this sentiment every chance they get.

#MeToo has often been accused of having “gone too far”, of steering the world in a direction where “believe all women” and “believe everything a woman says” are battle cries feminists use to usurp power from men. I exaggerate, of course, but it’s a concern that has plagued the minds of those who seem to worry more about men’s careers than women’s lives.

The Weinstein verdict, even as it acknowledges the complicated nature of sexual politics and power, cannot be said to have believed all women or everything a woman says – not by a long shot. It would be delusional to think that one guilty verdict would change the course of Hollywood or eradicate the very real problem of sexual harassment of women in the workplace. Weinstein is the poster-boy, not the problem itself.

What his conviction can do, perhaps, in time, is pierce the armour that powerful abusers seem to wear, convinced that they're too big to be toppled, too powerful to be reached.

And it can give the women of Hollywood the faith that if they band together, and keep to their cause for long enough, they can make the needle move, even though it might often seem like a Herculean task.

But for now, let's remember that we can, finally, with legal sanction, refer to him as rapist Harvey Weinstein.