"In the [US] Civil War, 186,000 black men fought in the military service, and we were promised freedom and we didn't get it," political activist Bobby Seale says during a montage of historic footage at the beginning of Da 5 Bloods.

”In the Second World War, 850,000 black men fought, and we were promised freedom and we didn’t get it,” he continues. “Now, here we go with the Vietnam War, and we still ain’t getting nothing but racist police brutality, et cetera.”

And now, in 2020, Seale’s words still ring disappointingly true.

Spike Lee’s new film, which was released on Netflix on Thursday, June 11, confronts the marginalisation of black soldiers in US military history.

Da 5 Bloods tells the story of four veterans who return to Vietnam in the present day to recover the body of their fallen comrade (Chadwick Boseman) and to claim gold they had buried more than four decades ago.

The film stars a number of heavyweight actors including Delroy Lindo, Clarke Peters, Norm Lewis, Isiah Whitlock Jr and Jean Reno.

Though the characters they play are not based on any particular person in real life, they stand as a symbolic homage to the black men who fought in the Vietnam War, as well as other US wars.

Below, we take a look at five of the most courageous and decorated black men in US military history, who could have inspired the characters in Lee’s newest film.

Doris Miller

Miller was a Navy mess attendant – a person who typically serves food to officers and crew aboard ships – who became the first African-American to receive the Navy Cross, receiving the distinction for his actions during the attack on Pearl Harbour in 1941.

Although he had no prior training to operate an anti-aircraft gun, Miller manned a weapon on his ship when the Japanese began attacking the Hawaiian naval base.

Miller fired the gun until the weapon was out of ammunition. When the attacks began to subside, he helped move wounded sailors, wading through oil and water, to the ship’s upper deck before it finally began to sink.

In January 1942, the Navy released a list of commendations for actions during the attack. Within the list was a single commendation for an unnamed black sailor.

The National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) asked US President Franklin D Roosevelt to award the Distinguished Service Cross to the unnamed sailor, who then sent his recommendation to the Navy Board of Awards. However, Miller's name remained unknown for a year until a 1942 story by the Associated Press identified the sailor, citing the African-American newspaper Pittsburgh Courier.

Miller died two years after the incident in Pearl Harbour, when a Japanese submarine torpedoed the ship he was serving on.

Frederick C Branch

Branch was the first African-American to become an officer of the US Marine Corps after he joined the division of the US Armed Forces in 1943.

His drafting came after President Roosevelt opened the Marine Corps to African-Americans through an executive order in 1941, which prohibited racial discrimination by any government agency.

Up until that point, African-Americans had been barred from enlisting in the Marine Corps.

Branch earned the recommendation of his commanding officer after serving with a supply unit in the Pacific War during the Second World War. He then received his officer’s training in the Navy V-12 Programme at Purdue University, where he was the only black student in a class of 250, and eventually made the dean’s list.

After the end of the Second World War in 1945, he joined the US Marine Corps Reserve. He came into active duty again during the Korean War, serving in an anti-aircraft training platoon.

He was discharged in 1952, and returned to the Marine Corps Reserve, but left in 1955 as he was still experiencing discrimination and promises for his advanced training were not met. In 1947, he went to teach physics at a high school in Philadelphia, until his retirement in 1988. He died in 2005 at the age of 82.

Milton L Olive III

Olive is brought up in Da 5 Bloods during a conversation about the romanticisation of the Vietnam War in Hollywood movies.

“I would be the first cat in line if there was a flick about a real hero,” Otis (Peters) says. “You know, one of our blood. Somebody like Milton Olive.”

Olive was only 18 years old when he sacrificed his life by jumping on a grenade to save his platoon.

A year later, in 1966, he was posthumously awarded the prestigious Medal of Honour, becoming the first black soldier to receive the award in the Vietnam War.

James Anderson Jr

Anderson Jr was a US Marine who took part in 1967's Operation Prairie III, which sought to eliminate forces of the People's Army of Vietnam, south of the Demilitarised Zone.

During the operation, Anderson Jr was moving with his platoon through the jungle, when they were attacked by North Vietnamese forces.

He died in action after he threw himself on a live grenade to save his teammates. He was awarded the Medal of Honour posthumously.

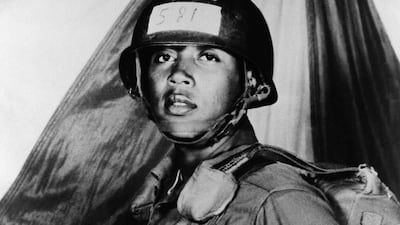

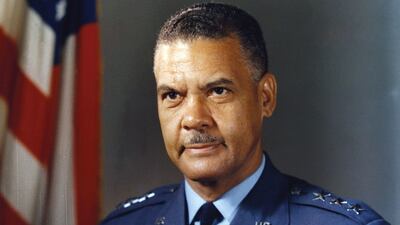

Benjamin O Davis Jr

Before Davis Jr became a general in the US Air Force, he was a commander of the Tuskegee Airmen – a group of African-American and Caribbean-born military pilots who fought in the Second World War.

The flying unit was created in 1941 after the Franklin D Roosevelt administration responded to public pressure for greater black participation in the military, especially with the impeding war.

Davis Jr was part of the first training class of the Tuskegee Army Air Field, which lent its name to the Tuskegee Airmen group, and became the first black officer to solo pilot an Army Air Corps aircraft.

Davis Jr saw active combat for the first time in 1943. He and his squadron were deployed in a dive-bombing mission – a tactic in which pilots dive directly at targets for greater bombing accuracy – against the German-held island of Pantelleria in Italy.

That same year, he was deployed to the US to take command of the 332nd Fighter Group, a larger all-black unit preparing to go overseas. However, he was faced with an attempt to stop the use of black pilots in combat by senior officials in the Army Air Forces. Davis Jr held a conference at the Pentagon to defend his men and presented the case to a War Department committee studying the use of black men in the military.

After the war, Davis Jr helped plan the desegregation of the air force in 1948. He then commanded a fighter wing in the 1950 Korean War and became a one-star general in 1954.

He became the first black officer to make the rank of a two-star general in the Air Force in 1959, going on to earn the rank of a three-star general in 1965.

In 1998 – almost three decades after his retirement – Davis Jr became a general of the highest order within US military when he was awarded his fourth general's star. He died in 2002 at the age of 89; he was suffering from Alzheimer's disease.