This week sees the return of Clint Eastwood to our screens. The actor-filmmaker is back with The Mule, a spin on a real-life story first brought to light in Sam Dolnick's The New York Times magazine article, The Sinaloa Cartel's 90-Year-Old Drug Mule. In reality, this ageing narcotics smuggler was called Leo Sharp; here the script changes his name to Earl Stone. Who better to play him – and direct his story – than the 88-year-old Eastwood?

Even so, it's remarkable that the four-time Oscar-winner is back so quickly. The Mule marks Eastwood's second film as director inside a year, after making another true story tinged with violence, The 15:17 To Paris, which starred the three actual Americans who foiled a terrorist plot on a train bound for the French capital. In The Mule, the octogenarian is also in front of the camera for the first time in seven years, since 2012's father-daughter tale Trouble With The Curve.

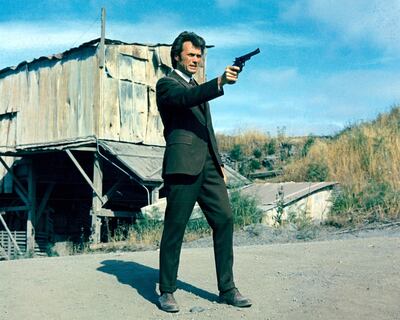

For an actor who started his career in the 1950s, coming to fame as Rowdy Yates in TV cowboy drama Rawhide, before gaining international acclaim as the cheroot-smoking sharpshooter in Sergio Leone's Dollars trilogy the following decade, he's really put his on-screen work on the back-burner these past years. Since 1995, when Eastwood turned 65, he's starred in only nine films – all directed by him, apart from Curve, which was made by his producer Robert Lorenz.

A role only Eastwood could fill

Yet it's not hard to see why he decided to return to the screen for The Mule. Earl Stone falls into that classic Eastwood category – the taciturn veteran out for one last ride. In the film, Stone is an award-winning horticulturist (OK, admittedly holding pruning shears isn't quite as dangerous as holstering a .44 Magnum like his rogue cop Dirty Harry) who has fallen on hard times. His daylily farm faces foreclosure and he needs money for his granddaughter's upcoming wedding.

You can probably guess the rest: approached by a Latino gentleman with a solution to his money worries, he's soon drug-running for the cartels from Chicago to El Paso – an ageing white gardener in a pickup truck being the perfect cover for smuggling kilos of cocaine. Featuring Bradley Cooper, his star from 2014's American Sniper as a DEA agent on his case, the twist comes with Stone donating his profits to worthy causes such as the local veteran's centre, which is in dire need of renovations.

Eastwood's 37th film as director, since making his debut with 1971's psychological drama Play Misty For Me, The Mule is his first time directing himself since 2008's Gran Torino, where he played a bigoted Korean War veteran. A spec script written by Nick Schenk arrived in a landscape of political correctness like a hand-grenade; as British newspaper The Guardian wrote: "no one else [but Eastwood] could conceivably have got away with the racist tirades, reactionary arias and bigoted broadsides".

Association with incendiary characters

The same character sketch is roughed out for The Mule, also written by Schenk, with Stone dubbing African-American characters as "negroes" and referring to the Mexican characters by the derogatory term "beaner". Like Gran Torino's Walt Kowalski, Stone was in the Korean War (likewise, Eastwood was drafted into the United States army in 1951 for the same conflict, although served out his time at California's Fort Ord as a swim instructor).

Eastwood’s own association with incendiary characters goes way back, of course, to Dirty Harry – which spawned five movies and became as defining in his career as his so-called ‘Man With No Name’ in Leone’s western trilogy. As Eastwood told a Cannes audience two years ago: “A lot of people thought it was politically incorrect. That was at the beginning of the era that we’re in now, where everybody thinks everyone’s politically correct. We’re killing ourselves by doing that. We’ve lost our sense of humour.”

It would, however, be too simplistic to paint the Republican-supporting Eastwood like these characters (not least because he's played so many different men, from tough to tender). What does appear to be a common thread is the way the actor loves to be the man out of step with the world, just like his ageing gunslinger in 1992's Unforgiven – the Eastwood-directed western that won him the first two of his quartet of Oscars (his harrowing boxing drama Million Dollar Baby came out of nowhere to pinch the other two).

Will this be his last film?

Is The Mule symbolic of his final "ride" into cinemas? Not if he can help it. "I never said it was my one last ride," he recently told one interviewer. "I like playing [someone on their] one last ride. Somebody was quoting me the other day 'This is your last movie'. I said, 'Maybe you're wishing that.'" Indeed, he claimed that Gran Torino was his last acting role a decade ago, proving how irresistible it is to get back in the saddle when the time is right.

If Earl Stone does turn out to be Eastwood's final movie role, it coincidentally arrives in the same year Robert Redford pitches up in David Lowery's The Old Man & The Gun. Six years younger than Eastwood, Redford has stated this turn as another real-life criminal – "gentleman" bank robber Forrest Tucker – will be his final screen outing. Just as The Mule borrows from Eastwood's own iconography, so too, does Lowery's film work as a comment on – and summation of – Redford's own career.

Indeed, there's something to be said for putting a full stop on a career on your own terms – finding that one last great role that says it all. In the case of The Mule, it's as much a reckoning with Eastwood's own life as it is his career. There are uncanny parallels, beyond the Korean War connection, prompted in part by his casting of his daughter Alison Eastwood as Stone's daughter Iris. While Stone is a man with a troubled relationship with his offspring, Eastwood has eight children from six women, including two ex-wives.

As he recently said in an interview: “Nothing was planned in my life, really. Certain things came about and I took advantage.” He’s talking about his career, of course, but he could just as easily be referencing his personal life. Maybe at this point, it’s impossible to untangle the two.

The Mule opens in UAE cinemas on January 10

___________________

Read more:

Nadine Labaki's 'Capernaum' nominated for a Bafta

How do film studios react when they know they’ve made a dud?

Do Golden Globe wins translate into Oscars? Not so much

___________________