As ebooks increase in popularity, typesetters are working hard to design the ideal fonts for on-screen reading - effectively creating 'invisible' type, writes Peter Robins In some jobs, invisibility is a sign of success. There is, for instance, one simple way to become famous as a bridge designer; engineers work hard to avoid it. The designers and typesetters who prepare the inside pages of books have similar incentives. Their task is to ensure that the ink on the page does not draw attention away from the world it describes. Not noticed? Then it worked.

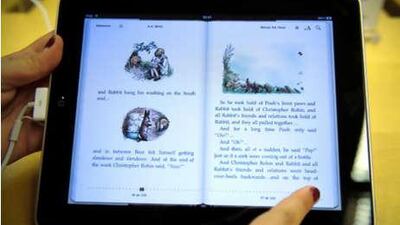

With the coming of ebooks, this invisible craft must be reinvented if it is not to disappear. Designers, used to tweaking a book so that no chapter ends with a few words on an otherwise blank page and no line of text is jarringly gappy or overstuffed, see much of their control handed over to readers or to device-makers. Design conventions that seemed immutable on paper cease to make sense. It is an upheaval as deep as any in the wars between Apple and Amazon, publishers and pirates - and it is taking place in front of readers' eyes.

"Designing a printed book is remarkably different from designing an ebook," says Charles Nix, a partner in the New York publishing firm Scott & Nix and the president of the Type Directors' Club. "Printed-book design is about fixed-size pages and spreads. Those are gone in ebooks. Book designers choose typefaces and point sizes to maximize legibility and comprehension. Those are gone in ebooks too. Some formats, he notes, do allow you to embed a font, but you can't rely on reading devices picking it up. Book designers finesse layouts and choose paper to achieve a particular bulk, weight, and feel for the finished book. Gone also."

Even some letters may be gone. Nicholas Blake, the editorial manager for digital at Pan Macmillan in London, shows me China Miéville's The City and the City on Adobe Digital Editions. The City and the City is a highly praised novel and Adobe Digital Editions is a heavily supported ebook platform, backed by the UK's largest high-street bookshop, Waterstone's, and with an implementation of the open standard for ebooks, Epub, more sophisticated than many. But The City and the City is set in an uncanny place called Be¿el; and one thing the platform did not permit, at least with its default font, was the character ¿.

Could they do without it? "We decided it was too important a book," says Blake. Besides, if publishers do not want ebooks cheapened, attention to detail is vital. "If you're paying the same price, you should get the same quality." So the company creating the file improvised a graphical ¿ of its own. Once you know, you can see it doesn't quite match the characters around it - but it does ensure the ebook of The City and the City takes you to the same world as the paperback.

Mirroring print isn't always the best policy, though. Some of the most familiar and readable book typefaces, for instance, can become a liability on screen or in e-ink. Reading on screen presents two special difficulties. The first is glare: the exhausting sensation that comes with concentrating on something that's emitting light. This is eliminated by e-ink panels of the sort used in the Amazon Kindle or the Sony Reader, and reduced by careful control of brightness on the iPad. But that doesn't help with the second difficulty - the one that, according to Phil Baines, a typographer and a professor at Central St Martins College of Art and Design in London, would most affect type choices. That is resolution: where a professional imagesetter can lay down thousands of dots per inch, a screen might have 96 pixels per inch, an e-ink panel between 150 and 200. "The much-hyped Retina display on the new iPhone 4 will have 326 pixels per inch - slightly finer than a 1980s laser printer."

Almost all text-heavy books are set in serif type - this kind, with little finishing strokes at the end of the letters, derived from the flick of a pen or the last blow of a chisel. Some argue that these extra strokes, or serifs, make text fundamentally more readable, by highlighting differences between letters or guiding the eye along the line; others say we're just used to them. It's a brave designer who prints a novel in sans-serif type, or suggests it as the default for an e-reader. But the old-style serif types favoured in books have another refinement: the weight of the strokes within the letters varies, as if they were produced with a chisel or a flat-nibbed pen. On screen, these delicate contrasts can be difficult. The thin bits can vanish. As Baines notes, web designers often prefer sans-serif types, without such complications.

There are ways to improve old-style serif fonts on screen. Good typefaces contain "hinting" - information on what to keep when pixels are in short supply - and shades of grey can imitate finer detail: this is called "anti-aliasing". But there are limits. The results of hinting, Nix told me, are "anything but universal", and even then "not all devices utilise the hard-won hints". Anti-aliasing isn't magic, either, especially on an e-ink panel with 16 shades of grey.

This is why Apple's iPad has run into significant criticism from designers, not only for a lack of book-like control - iBooks doesn't currently let designers embed fonts, and there are reports of it having difficulty handling tables - but for prioritising book-like looks over readability on screen: it goes as far as offering an imitation of the shadow that a book's spine casts on the page. The five fonts it offers readers consist of one sans and four ill-assorted serifs. In a stinging blogpost on "What the iPad is missing", the design critic Stephen Coles has written that only one of the options, a robust book type called Palatino, is a "legitimate choice for reading on screen". Nix finds the iPad "something wonderful" - "a device out of early science fiction" - but his praise doesn't extend to how it handles ebooks: "It's a black mark on Apple's long history of championing typographic refinement. The typographic choices (for the reader, not the designer) are limited and in most cases nonsensical."

Amazon, by contrast, although its Kindle offers designers limited control, found an elegant compromise. Its default font - PMN Caecilia - has almost no variation in stroke weight but derives its letter shapes from traditional book type. Even device companies that put a premium on print-quality design look for screen-adapted text. Sarah Gaeta, a vice president at Plastic Logic, which has leading US magazines and newspapers making custom editions for the large e-ink touchscreen of its Que reader, told me its aim was to offer something as "graphically rich" as the print versions. This doesn't mean, however, that it is keen for the Wall Street Journal or Fast Company to stick with their familiar serif text. "Users are responding very well to sans serif fonts," she says. They don't force this on their partners - "ultimately it's their choice" - but the advice is clear.

The advantages of electronic formats require as much rethinking as the limitations. When a file can be used on different-sized screens, and users can scale up the type, all that work to ensure evenly coloured lines and nice page-breaks must be done by the device, if it's to be done at all. Then there is the length of the lines, a particular concern for Nix: "Short lines are 'telegraphic' length - more suited to news or other short bursts of information. Longer lines are 'thought' length - allowing enough words for more complex sentence structure through meaningful groupings of words."

The screen sizes of the Kindle and Sony Reader make for lines slightly shorter than standard in books; an iPhone or an e-reader with the typesize increased, much shorter. Shorter lines also cause problems for justification (the smooth edges at either end of a page that most readers expect), especially as many e-readers don't yet do hyphenation. Unjustified text, with the right margin left ragged, may help, but long words may cause problems even then. Blake reports trouble with The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, where the sigh of satisfaction emitted by the automatic doors - a string of "m"s - can disappear off the edge of the screen. Like the Kindle, the iPad forces its books into justification without hyphenation. "This was one of the more obvious ways in which Apple could have one-upped the Kindle," writes Coles, "and they dropped the ball."

Should we expect such details to improve? "Absolutely undoubtedly," says Blake, simply because publishers are paying more attention. "Two years ago there were publishers' chief executives who'd never seen an ebook. If there are any now, they won't admit it." The attention has increased with the arrival of the iPad: its colour screen should open whole new markets to electronic formats, such as books for younger children, and it also offers a promise of increasingly interactive books. "If you talk to me in a year's time," says Blake, "it will all be different."

Plastic Logic's Gaeta, as you might expect, is more sceptical: the iPad, she says, has also to focus on video, and games, and will struggle to match e-ink devices for "immersive reading". Nor does she expect huge leaps in sophistication for formats such as Epub: "One aim of the format is to try to make fairly lightweight files that don't require the heavyweight typographical rendering capabilities of something like [the professional layout program] Indesign." Books that need elaborate features will come in more complex formats - such as PDF, used for the magazines and newspapers on the Que.

There is another possibility: that our expectations will shift to meet the format, rather than the other way around. "One thing about the web," says Baines, "is that we've all become much more used to bad typography." Internet users cope daily with line lengths and colour schemes that would once have been outlandish barriers to reading. We can only hope that ebooks won't have the same effect. Peter Robins works for the media and technology section of The Guardian in London.