“Most of what I do is fairly pessimistic in its perspective. This book may be more so in terms of the guilt that the characters are bearing and the suggestion of an element beyond realistic events, an element hovering around as a kind of revenge. There is something out there that is making us pay for our indulgences. Sometimes I think you wake up in the morning thinking, What am I getting away with today?”

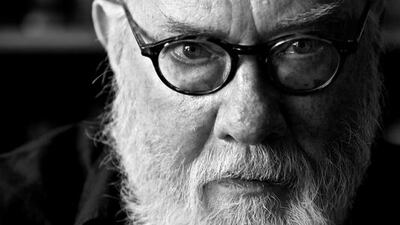

Robert Stone, the award-winning and revered American novelist, has reasons to be both cheerful and somewhat glum. On the upside, he has just published the superb Death of the Black-Haired Girl [Amazon.com; Amazon.co.uk], his first new novel in a decade and the ninth in a career spanning almost 50 years. "Procrastination," he says of his sluggish productivity. "If they were giving out trophies, I would have one."

Time has suddenly become newly pressing for the dilatory Stone, who turned 77 last month. When I speak to him from his Massachusetts home, he reveals he is facing a somewhat uncertain literary future. “I am really in a spot because my right hand is for the foreseeable future useless.” The injury was the result of a heavy fall. “It seems to me I was sober,” he adds laconically. “I really did a number on my hand.”

It is every writer’s nightmare, especially one whose finely wrought prose is the product of long hours working at the typewriter and in longhand. In addition to the acupressure treatment that delayed our first conversation, Stone is being taught to use speech-recognition software by his grandson. “I am going to have to learn to dictate, which is something I really can’t do. I have got to have it on the page. But I’ll have to do it if I am going to get anything done at this advanced age.”

The accident leaves the melancholy prospect that Death of the Black-Haired Girl could be Stone's final novel. It has been hailed, not least by his publishers, as his first crime novel. The cover mixes glowing encomiums from Jennifer Egan with blurbs from The New York Times heralding a "sure-footed psychological thriller".

It is a label Stone accepts, albeit grudgingly. “I once had a novel that I was quite attached to which ended up, in Finland anyway, under the category of ‘Crime and Horror’. It made me feel like I had done something really, really dreadful.”

Nevertheless, the superficial genre similarities did not escape him. “There is a killing, a lot of guilt and intrigue – not a few secrets. It has this element of crime, which I am not apologising for. It is not of course a whodunnit. I didn’t think of having to satisfy the requirements of the genre. It is character-driven. If it were plot-driven I think it wouldn’t succeed.”

Stone's best work has always negotiated this path between serious literature and, for want of a better phrase, more exciting narrative pleasures. Dog Soldiers [Amazon.com; Amazon.co.uk], the 1974 novel that won the National Book Award and which many consider his masterpiece, was both a suspenseful melodrama and an incisive, terrifying account of Vietnam and America's counter-culture. The New York Times declared 1981's A Flag for Sunrise [Amazon.com; Amazon.co.uk] "a first-class thriller [that] catches the shifting currents of contemporary Latin American politics".

“At the end of the day, you are an entertainer,” Stone says, a little unexpectedly. “I don’t know whether it is trying to be loved or what, but one is an entertainer.”

Death of the Black-Haired Girl fuses two well-trodden genres. There is a campus narrative, inspired by Stone's own adventures teaching at Ivy League schools. "I savoured this as some kind of ironic revenge. My own formal education was very limited. I really got into the academic milieu through what I had written." His heroine is the brilliant, beautiful but unstable Maud Stack, who is embroiled in a passionate, doomed affair with her professor, Steven Brookman. "Maud is a very ambiguous character. She isn't honest. She isn't diligent. She is self-indulgent and vain. I love her dearly. She has a great deal to learn, had she but time to learn it."

The daughter of a tough Brooklyn cop, Maud is the novel’s centre and its victim. The question of a perpetrator is far trickier. “There are a lot of people letting other people down, people failing each other. There are also people coming through for each other, or trying to.” Chief among these is Brookman himself, who betrays Maud, his pregnant wife, his young daughter and his colleagues. “The deeper I went into Brookman, the more of a rat he seemed. He isn’t loveable. He is selfish. He is cold. He is my point-of-view character, and I am stuck with him. [Brookman] is as deeply lost as anybody in the book, and God knows everybody in the book is lost in space.”

The novel’s second half teases with suspects. Was Maud’s death a tragic accident or a tragic murder? Hoping to impress Brookman, she had written an inflammatory article for the student newspaper mocking religious zealots protesting against an abortion clinic, inspiring a torrent of threats.

For Stone, the plot twists are secondary to his efforts to observe, describe and critique contemporary America. “I think I was writing about the ways things are now, the ways things have become over the course of my lifetime, which is pretty long.” When I ask what he means by these “things”, his response hits that pessimistic note mentioned in the opening quote. “The selfishness, the dispensing with responsibility on any serious level. It really is about selfishness, about greed, self-satisfaction. A loss of perspective that we might have hoped we had been born with that is somehow disappearing.”

The tone of righteous anger is hard to miss as Stone launches broadsides against America’s economic inequality, class divides, religious fundamentalism, secular self-satisfaction and moral crises from mental health to sexuality, family to education. “We have really done dreadful, irresponsible things to our education system. It is particularly bad in terms of race. The big city schools are overwhelmingly black or Hispanic. I think the ignoring actually touches on corruption – putting money in someone else’s pocket. That may be an exaggeration. But it’s going to come home to roost.”

Nothing exercised Stone more completely than the furore surrounding abortion in America. “There is no question about where I stand in this absurd and hypocritical fight. It is so charged with hypocrisy, and the cheapest kind of political posturing that by itself is something to be ashamed of. I mean, how grossly self-serving.”

In the novel, Maud’s crude satirical assault apeing the protesters’ shock tactics earns her universal vilification – not only from the targets of her mockery, but also the self-serving liberals seeking to protect themselves from the ensuing controversy. “I would have made it more provocative,” Stone declares defiantly. “It is the one thing I reproach myself with that I didn’t. I wrote about religious posturing and that whole anti-abortion demonstration with a great deal of satisfaction and bitterness. I really had a good time putting it down. I am with Maud 100 per cent. Whatever she is being punished for, it is not that.”

Stone finds it harder to articulate the novel's more mystical episodes: its depiction of a divine or nearly divine vengeance. "You find yourself in the core of a novel you didn't necessarily set out to write. Not to complain or apologise, but I felt at times I was lost. I had to find my way out." In this, Death of the Black-Haired Girl isn't a whodunnit so much as a morality tale asking whydunnit. The killer is not the only person guilty of Maud's death. "A degree of moral responsibility is at loose in the novel that sometimes felt to me almost supernatural. I think I was headed for something beyond realism."

The origins of this mystical dimension can be traced to Stone’s formative years. He was born in Brooklyn in 1937 – you can hear traces of his birthplace in the way he pronounces “part” and “heart” (“pawt” and “hawt”). “I was lucky because I grew up in New York, not some remote farm or mountain. I was in the centre of Manhattan. It wasn’t a privileged situation but it was a great place to be.”

Location did guarantee happiness. Stone’s mother, a schoolteacher, suffered from schizophrenia and was committed when her son was 6. “Whatever else she was she was independent,” he says evenly. “She was an absolute loner, except for me. She didn’t get close to people, she didn’t have friends. She was a very odd duck. An odd, odd duck. She was something else.”

Raised in a series of Catholic orphanages, Stone fell in love with books, possibly in a first attempt to escape these traumas. “From early on, I was finding my pleasures in stories. I liked poetry. I guess that is one thing that cut me off from the next kid. It was a love of language. That was my high when I was 12 or 13.”

Stone may have been a precocious reader, but the idea of writing for a living seemed inconceivable. “I never imagined it was something I was going to do with my life. I did admire journalists and the whole romance of the war correspondent, the political correspondent. I had hopes for that but didn’t pursue the education for it.”

In 1954, Stone joined the navy. He was 17. I mention certain similarities between his biography and that of snaky Stephen Brookman, who was also a merchant seaman before becoming a writer-academic. “I share a lot of things with Brookman in terms of circumstances. I went into the military when I was very young. I didn’t have very much else to do. I didn’t finish my secondary education. I just quit and went into the navy. God knows I could have stayed there.” Why didn’t he? “It wasn’t what I was going to do. I was so young when I went in, really a kid. I was 21 when I got out. I felt very sophisticated. I felt I had seen the world. I had seen the world. I couldn’t do much with it, but I had seen it. That was really my preparation for things I did later.” He pauses. “I hope fundamentally Brookman is not me. God save us.”

Stone’s career as a novelist is marked by a similar desire to engage with American society without being confined to it. He has spent a lifetime criss-crossing the globe – from Egypt to London, from Australia to Antarctica – and writing books set variously in Vietnam, Nicaragua, Mexico and Jerusalem. “You felt that wherever authenticity was, it was where you weren’t. Somewhere out there was true authenticity, but how to find it? I never found it! I am still looking.”

This restlessness and rootlessness was both inherent and inspired by Ernest Hemingway’s example. “[I wanted] to be where the world was happening. When I was about the right age, Hemingway was God. If you could have Hemingway’s life, you would trade your own in a minute. My God! Drink and women and Africa. Hemingway was it for my generation. He had his faults and his indulgences, but by God the man could write. At his best there is hardly anyone better, unless it is Fitzgerald.”

I ask whether The Beat writers, Stone's immediate predecessors, were comparable influences. "I liked for lack of a better word the hipness of Kerouac. But I don't admire Kerouac's writing at all. I think Kerouac at times is just dreadful. If you compare the end of The Great Gatsby to the last pages of On the Road, you can see the incredible differences. Ye gods."

Stone came of age as a man and a writer during the 1960s' counterculture: his debut novel, A Hall of Mirrors [Amazon.com; Amazon.co.uk], was published in the Summer of Love. His memoir Prime Green [Amazon.com; Amazon.co.uk] documents this period, and his close friendship with Ken Kesey – the author of One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, psychedelic pioneer and "Merry Prankster" famed for the 1964 bus trip across America that Tom Wolfe memorialised in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.

“Kesey was a great optimist. He really saw things like Kennedy’s election and the entire 60s as [America] getting better in a hurry. People were going to the Moon. I am sure he would be very disappointed [by America today]. I was never an optimist in the way he was. In fact, he thought I was kind of a joke. My negative point of view he found amusing. I think I was just seeing straight. We were very good friends probably because we saw things so differently.”

Seeing differently was an intrinsic part of the 1960s. Stone lived up to his name and experimented with altered states. “Drugs were a big part of things, no way around it. We were around the beginnings of LSD. We saw this as some kind of magical reformation, but of course it cost an awful lot of people an awful lot – including their sanity. It really wasn’t the blessing we might have hoped it might have been.”

Did drugs ever help Stone creatively? “I think so,” he replies thoughtfully. “For me. I was just on the right side of that. Sometimes it was pure ekstasis and you loved it, and other times it was terrifying. I think I benefited from it in terms of insight – in terms of introspection and observation of the exterior world around me. I learnt a lot.”

One insight sounds very nearly like a spiritual conversion, and counterbalanced an earlier disavowal of his childhood Catholicism. “I had a quite secularist and cold-blooded attitude towards religion – contemptuous – which after getting into the drugs a little, I lost. I became convinced that there was simply more out there than I had suspected. I don’t know how it stacks up now.”

Stone is far from having any orthodox belief system, however. “Faith is not like believing a series of theological principles. It is of the heart. It is an attitude deeper than that.” He doesn’t believe in life after death, for example. Indeed, he doesn’t consider death, full stop. “I just take it as part of the deal. It’s not something I spend a lot of time thinking about.”

His signature pessimism certainly has plenty to latch onto these days, in both his interior and exterior universes. He sounds disillusioned, if kindly towards his current president. “I feel sympathetic to Obama. I think it was a great thing that he was elected. I just don’t know how much power he has to effect things.”

Stone’s recent injury has injected new anxiety and urgency into his protracted creative process. “I need more time than I have,” he says of his demanding creative process. “It is partly just plain laziness. I certainly require immense amounts of time. I will let weeks go by and I get to feeling terribly guilty.”

The antidote is retaining a sense of humour about his frailties and awareness of what makes life worth living: love, family, the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins, and art. And then there is always the promise of something beyond this reality. Stone gives it its proper name.

“I have never really seen the things I do as realist in the old-fashioned sense. I have always felt there was a level, for good or ill, that was somehow beyond, above, below the strictly realist. And that sometimes I think was hope.”

James Kidd is a freelance reviewer based in London.