Overbooked: The Exploding Business of Travel and Tourism

Elizabeth Becker

Simon & Schuster

Dh94

For too long, argues the author Elizabeth Becker, the tourism industry has been treated as anything but. Tourists, she writes in her highly readable new tome, Overbooked: The Exploding Business of Travel and Tourism, rarely think of travel "as one of the world's biggest businesses, an often cut-throat, high-risk and high-profit industry". Instead, they're thinking about suntans, new locales, "and the liberating freedom of taking a break from their own lives", Becker maintains.

It may surprise many of the sunburnt beachgoers out there that tourism is the biggest - that's right, the biggest - industry in the world. In 2007, the first global accounting system revealed that tourism contributed US$7 trillion to the world economy and was (and is) the largest employer, with 250 million associated jobs.

Clearly, "global" becomes "local", because tourism can have a huge impact on the economies of the world's poorer nations, such as Zambia, Cambodia and Sri Lanka - all of which figure into Overbooked - as well as richer nations such as the United States, China and France (now the planet's number one destination). Travel, moreover, has global political and philanthropic implications. "Tourism is the greatest modern voluntary transfer of wealth from rich countries to poor countries," declares David Hawkins of George Washington University in Washington, DC. Hawkins, who is the institution's Eisenhower professor of tourism, once represented the US before the UN World Tourism Organization - yes, there actually is such a body - until the US pulled out for political reasons, but more on that later.

The point is that it has become difficult for the UN or any other entity to measure, much less control, worldwide tourism, the "octopus-like" tentacles of which, Becker points out, now embrace issues as diverse as coastal development, child prostitution, the treatment of religious monuments, and the survival of threatened bird species and native cultures. There is even "dark" tourism (meaning the fascination many people have with places like Cambodia's notorious Tuol Seng prison, the torture/execution centre run by the Khmer Rouge).

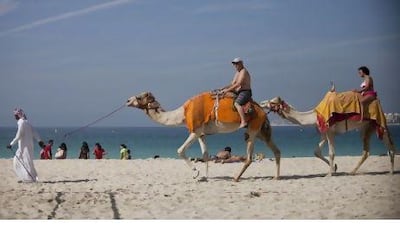

Lighter categories, such as shopping tourism, figure in as well, says Becker, who jumps off here for a chapter about Dubai and its particularly rich retail opportunities. "Today, Dubai is considered a model for tourism in the 21st century," Becker writes, calling the city's malls legendary for selling more brand names than anywhere but London. Dubai also welcomes three times as many foreigners as New York City, she notes.

But UAE readers may not be as pleased with the rest of the author's message. "A journey through Dubai - and Abu Dhabi - is a practical course in tourism and its future. It is a pretty frightening one, too," she writes, opining that Dubai and the Emirates in general "are models for the overconsumption that is threatening the planet".

She underscores that stance by describing how Dubai has strived to become one of the major hubs in the airline world - Dubai International is set to be the world's busiest airport by 2015 - and how more energy per person is expended there than almost anywhere in the world.

Still, other nations are also taking notice and looking at ways to mine their own unique riches and thus boost tourism along with their economies.

Zambia is a good example, given its elephants, baboons and hippos, which bring in safari-minded tourists. Copper is still king in Zambia, but tourism to this African nation contributes $1 billion a year and that figure is growing. Becker focuses on South Luangwa National Park, where from 1975 to 1989 the elephant population was decimated, until conservation became a priority, not only to save these magnificent creatures but to save tourism.

Key to this mission have been heroes such as Richard Leakey, scion of the famous paleontologist family: in 1989 Leakey held a public bonfire in Kenya, destroying 2,000 elephant tusks seized from poachers - worth an estimated $3 million on the Chinese alternative medicine market.

Another hero - surprisingly - has been Paul Allen, cofounder of Microsoft, who invested the funds needed to upgrade Luangwa's camps and lodges. The government of Norway has also donated generously to Luangwa.

"In the United States, people realise they have to manage the wildlife," Luangwa administrator Andy Hogg told the author. "In Zambia, it's let's let nature take its course." For years, the authorities turned a blind eye to poachers, but that attitude needs to change, enlightened Zambians now understand, because animal conservation equals tourists. As Zambian tourism minister Catherine Namugala said at a conference: "Tourism is one of the few key sectors that can impact on poverty."

That lesson is key to the future of a nation like Sri Lanka, which, freed from the chaos of war, is busily selling off its pristine beaches to the resort industry - with all the pollution it brings - even as the national tourism board lobbies for public beaches and small-scale hotels. Then there's Cambodia, which Becker calls "a model of tourism gone wrong". This is because tourism profits there rarely filter down to the average citizen (earning just Dh7,300 a year). Whole communities, in fact, are being evicted to make way for new resorts. And the tourist hordes are being allowed to destroy Cambodia's national treasure, Angkor Wat. Only efforts by outsiders may yet save these magnificent temples from sinking into the earth as surrounding hotels slowly drain the water table.

On tourism's brighter side sits France, which edged out the US as the number one destination globally simply by taking the industry seriously. "The French understood before most other countries that tourism is a serious business, integrating it into major government policy decisions," Becker writes. In 1936 the government mandated a paid two-week holiday for its citizens, which the French call "Les Vacances". The government also introduced subsidies to preserve picturesque small farms, and grants to speciality labels to ensure the survival of French agricultural products and cuisine. Before any region in France opened up to tourism, it first had to draw up plans for preserving its local quality of life and for niche marketing. "Niche" examples include camping for the Dutch, urban holidays for Americans, and cultural events for Brazilians. "Our accent is on cultural tourism, on local tourism," French tourism agency representative Christian Delom told Becker. "We make great efforts to oblige tourists to meet French people."

But what about the obstacles some foreign visitors encounter actually meeting locals? That's what occurred in the US post-9/11, when tourists complained of difficulties obtaining visas and of what the UK newspaper The Times called the "spirit-crushingly frosty reception" they received when they arrived in the US. Men from Muslim countries were particularly targeted.

Nor did the US government do much to reverse the declining interest in visiting the country and the resulting drop in revenue. The US had already withdrawn from the World Tourism Organization in 1996 and refused to rejoin in 2003, citing budgetary pressures. And despite tourism's six per cent contribution to GDP, the Republicans withdrew funding for the government's Travel and Tourism Administration. Apparently, the nation that invented national parks (Yellowstone) and theme parks (Disneyland) just didn't care.

China has been just the opposite. And here's where Becker's skills as a reporter (she's a former foreign correspondent for The New York Times) enriches Overbooked. Her conversations with locals in the tourist trade turn what could have been dry data into colourful, often inspiring prose. So we learn that formerly closed-up China has jumped full throttle into tourism - even mandating "golden weeks" off for its own citizens - and that by 2020 it will replace France as the world's leading destination.

But the up-close experience of travel there can be alarming: censorship is still in force; so are low wages, outlawed strikes, and hotels that look like old-style Chinese architecture but are actually fakes - "a history park, not real history", as Becker's guide puts it.

It's sad when that same guide tries to deny severe air pollution in the town of Xian (home of the famous Terracotta Warriors) as "yellow mist ... fog" - the official government line. It's also sad to read how, when a British researcher asked a little girl in Gambia what she wanted to be when she grew up, she replied: "A tourist, because tourists don't have to work and can spend their days sitting in the sun, eating and drinking."

Joan Oleck is a freelance writer based in Brooklyn, New York.