Wesley Yang reads Jane Mayer's acclaimed study of the American turn to torture.

The Dark Side

Jane Mayer

Doubleday

Dh125

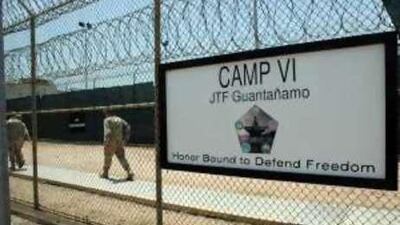

When the United States government decided to "take the gloves off" in the interrogation of detainees captured in the War on Terror, it looked to various sources for guidance. Jane Mayer names them all in The Dark Side, with a particular emphasis on the scientists who turned their knowledge of the human personality to dark purposes. She reports on the psychologists who, in direct violation of their most basic ethical commitments, provided care to the inmates at Guantanamo Bay - and then advised interrogators on how best to break them. The core of her book - the vital piece of the story that Mayer herself broke in the pages of the New Yorker - is her disclosure of the role played by military trainers who formerly taught American soldiers how to withstand torture. These experts "reverse engineered" their techniques to help the CIA design a protocol for questioning the 14 "high value detainees" (including Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the mastermind of the September 11 attacks, and Abu Zubaydah, the alleged "operational head" of al Qa'eda, who turned out to be mentally unbalanced) they were holding in secret "Black Sites" around the world.

The detainees were subjected to extremes of hot and cold, bombarded with sounds and lights, stripped naked and doused with cold water, deprived of sleep, forced into painful "stress positions", shackled by the wrists from the ceilings in a position that required standing on tiptoes for eight hours at a time, sexually humiliated in various ways, threatened with dogs, slammed against walls, forced to wear dog collars and deprived of any sensory stimulus at all for months on end. The idea was to induce the "learned helplessness" that psychologists had shown it was possible to create in dogs. They were also waterboarded - hung upside down while water was poured over their mouths and noses to create the sensation of drowning. As we now know, they began to speak at length. They revealed some details already familiar to the intelligence agencies, helped to fill in some of the gaps in our knowledge of how the September 11 attacks were executed - and spewed a great deal of alarming nonsense (false confessions and concocted plots) that sent American investigators on a wild chase after illusory leads.

One problem with these techniques was that they were contrary to American and international law; another problem was that they could brutalise the sensibilities of the men enacting them (look back at the Abu Ghraib photographs for a reminder); yet another problem was that many of them had been developed by the Soviets for the purpose of extracting false confessions from political prisoners, a goal that is, on the face of it, antithetical to the discovery of "actionable intelligence". Or, as one military officer warned, the techniques were "immoral, unethical and they won't get good results." Mayer traces the way these methods spread from the tightly controlled settings of secret CIA detention centres outward to the military prisons run by the Department of Defense in Guantanamo, Afghanistan and Iraq, growing unmoored from their ostensible purpose (as brutality will often do) and culminating in the abuses at Abu Ghraib and the murders of at least four detainees.

The practices used against the high-value detainees were expressly authorised by the CIA's Deputy Director of Operations, James Pavitt, and openly discussed by Dick Cheney, Condoleezza Rice, John Ashcroft, George Tenet, Colin Powell and Donald Rumsfeld. They were permitted by a secret legal opinion issued by the Attorney General's Office of Legal Counsel, the executive branch entity responsible for advising the President what the law permits him to do. An OLC memo written in August 2002 defined torture as a crime that was nearly impossible for anyone to commit (an infamous passage argued that abuse was not torture unless it was "equivalent in intensity to the pain accompanying serious physical injury, such as organ failure, impairment of bodily function, or even death") and asserted that the President had the inherent prerogative to do anything he deemed necessary to defend the country, regardless of what the law said about it. This remarkable legal doctrine, which empowered the president to govern as a lawless dictator in a war without temporal or geographic limits, was the chiefly the product of two men: Dick Cheney's legal counsel David Addington, and a midlevel OLC official named John C Yoo.

The doctrine was the legal expression of Cheney's long-standing political goal of expanding - he would have called it restoring - the discretion of the President to act decisively, unencumbered by judicial oversight or Congressional interference. Yoo and Addington, who were, for a time, "running the War on Terror almost on their own," as one official told Mayer, pursued this agenda with a singular ruthlessness neatly summarised in Addington's promise to "keep pushing and pushing and pushing until some larger force makes us stop."

Addington and Yoo's legal creativity, which resembled "the advice of a mob lawyer to a Mafia don on how to skirt the law and stay out of prison," as Anthony Lewis put it, enabled the government to engage in the warrantless wiretapping of American citizens, the indefinite detention without charge of suspects captured in Afghanistan, and the "extraordinary rendition" of suspects in the War on Terror, who could be snatched up by American forces anywhere in the world and sent to the prisons of Egypt, Syria, Thailand, or other temporary partners in the War on Terror for "aggressive" questioning. This so-called New Paradigm began to emerge when the government declared that detainees captured in Afghanistan were not eligible for protection under the Geneva Conventions, which the United States had both initiated and signed. It eventually met its demise in a series of Supreme Court decisions that reversed the President's claims of unlimited authority.

The story has already been told by the mainstream American press, that embattled institution, which prised it from the grip of the most secretive administration in American history. But Mayer has added to this record a remarkably poised narrative reconstruction of these disclosures that will permit those who are so inclined to relive the most wretched episodes of the Bush era. In the end, Mayer demonstrates, all the most important information - such as the whereabouts of Khalid Sheikh Mohammad - was almost always generated by non-coercive means.

The book relies heavily on the testimony of those Mayer calls "patriotic critics inside the administration and out who threw themselves into trying to head off what they saw as a terrible departure from America's ideals, often at an enormous price to their own careers." These include experienced FBI investigators who had successfully prosecuted terrorists through patient, non-coercive means, establishing some of the best information we have on al Qa'eda; official military defence lawyers who issued sternly dissenting opinions to Pentagon policies that condoned torture; and the former head of the Office of Legal Counsel, Jack Goldsmith, a hardline conservative and friend of Yoo who found himself repealing OLC decisions on warrantless wiretapping and rescinding the "golden shield" protecting CIA interrogators from prosecution established in the Yoo torture memo.

Perhaps the most courageous of these critics was the former Navy General Counsel Alberto J Mora, who led an effort within the Pentagon to end coercive interrogation at Guantanamo. Mora believed that torture was contrary to American values and the practices of the United States military. He is right about this. America's founders were steeped in Enlightenment values that abhorred torture: George Washington outlawed the torture of British soldiers, and the American military has never openly condoned the practice, even when it faced enemies, such as the North Vietnamese, who employed it. "The debate here isn't how to protect the country," Mora declares. "It's how to protect our values."

The polemical energy of Mayer's book comes from her outrage at the violation of these values. In her introduction, she characterises the Bush Administration's conduct in the War on Terror as "a quantum leap beyond earlier blots on the country's history and history," and "a dramatic break with the past." She invokes the judgment of the eminent liberal historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr, that "no position taken has done more damage to the American reputation in the world - ever."

But Mayer overplays her hand, going on to write that "in fighting to liberate the world from Communism, Fascism and Nazism, and working to ameliorate global ignorance and poverty, America had done more than any nation on earth to abolish torture and other violations of human rights." Here Mayer confuses the fact that America has always supported human rights in principle with the idea that it has always championed them in practice.

The tactics of the New Paradigm, after all, did not have to be invented from whole cloth. After September 11, Cheney turned to the CIA's archives in search of examples that had worked in the past. "He was particularly impressed," Mayer writes, "with the Vietnam War-era Phoenix Program. "Critics, including military historians, have described it as a programme of state-sanctioned torture and murder. A Pentagon contract study later found that 97 per cent of the Viet Cong it targeted were of negligible importance. But as September 11, inside the CIA, the Phoenix Program served as a model."

Mayer doesn't have another word to say about the Phoenix Program, and her reticence is telling, in a book that is otherwise so exhaustive in the way it details the histories of its major players and the institutional background of the responsible agencies. The Phoenix Program was a CIA-directed operation to interrogate, detain or assassinate a network of Viet Cong insurgents who were themselves torturing and assassinating South Vietnamese officials. A Senate investigation later concluded 20,000 Viet Cong were killed in the process.

Mayer doesn't specify what Cheney took from the Phoenix Program, but he certainly found confirmation that we had done these things before, and on a massive scale. CIA interrogation manuals issued in 1963 and 1983 and used by American client states in the proxy battles of the Cold War in Latin America and elsewhere also listed ways to force a recalcitrant subject to talk. She quotes a historian of the CIA noting that our latter-day torturers not only used those techniques, "they perfected them" - underscoring the fact that they were already there to be perfected.

Mayer is too scrupulous a reporter not to mention these departures from American values. But she is also too committed to a particular narrative - in which America's status as the country that "had done more than any nation on earth to abolish torture and other violations of human rights" has been suddenly hijacked by bad men in the Bush administration - to follow that disclosure to its conclusion.

Which is simply this: America has always remained true to its values - except in the rather numerous instances when it has violated them. While the struggle to defeat Fascism and Communism were worthy endeavours for which America deserves historical credit, both wars were fought in ways that would have landed American presidents before a war-crimes tribunal, at least according to the human rights standards that Americans have helped to foster, America's struggle against fascism included the only military use of nuclear weapons by any nation and the firebombing of German cities for no strategic purpose other than terrorising civilians; America's war against Communism involved training our client states in the use of assassination and torture - often against very bad men who were torturers and murderers themselves.

These are the genuine paradoxes of power that no nation-state aspiring to global leadership can evade. Americans confronting a world of enemies who wish to do it harm have responded to those threats with varying degrees of restraint or its absence, stupidity or wisdom, and have compiled in the process a long and extremely mixed record of both heroism and abuse - sometimes fatally intertwined - that absolutely rules out the kind of wounded innocence that Mayer repeatedly sounds throughout The Dark Side. That she can sustain this view - and in this she resembles almost every other mainstream writer on the subject - in the face of her knowledge of precedents like Operation Phoenix, and despite the relentless rigour she brings to the pursuit of the darkest truths, testifies to a deeply ingrained predisposition of a certain kind of liberal: those who wish to reconcile a heroic view of the American past with a moralistic approach to foreign affairs.

This matters not just because we should have our historical record straight; it matters because illusions about inherent American virtue are precisely what has led a whole class of well-intentioned Americans to misjudge the limits of American power and its capacity to do good in the world. And that misjudgement is as relevant to the calamity of the last seven years as any of the failures Mayer so meticulously describes.

Wesley Yang writes for Nextbook and n+1, and has reviewed books for the Los Angeles Times Book Review, New York Times Book Review and the New York Observer.