During the 2016 United States presidential campaign, property tycoon and reality TV personality Donald Trump frequently promised that if he were elected, he would go to Washington and “drain the swamp”, removing career political hacks and bringing in new blood. When he was elected, however, in addition to packing the White House with relatives and controversial figures, he picked a long-time swamp-dweller for one of the most important jobs, appointing Republican party apparatchik Reince Priebus as his chief of staff.

It is by default a tremendously consequential decision. As journalist and documentarian Chris Whipple points out at the start of his invigorating new book The Gatekeepers: How the White House Chiefs of Staff Define Every Presidency, "the fate of every presidency arguably hinges on this little-understood position".

Under normal political circumstances, the choice of chief of staff is weighed up for some time, a decision influenced by range of factors. Who has the managerial skill to manage the hundreds of people jockeying for the president’s attention? Who has the networking finesse to reach out to leaders of Congress in ways that help the administration’s agenda without compromising the president? Who has the intellectual clarity to keep the bigger picture of the Oval Office job in view, and the personal courage to make sure the president never loses sight of it?

“The chief must be the gatekeeper who decides who sees the president,” writes Whipple. “He must almost always be in the room to prevent end runs by people pushing their own agendas.”

Whipple interviewed each of the 17 surviving chiefs of staff for his book, and two former presidents. Anyone who has ever interviewed a public figure and encountered a deeply-ingrained ability to avoid saying anything pointed or memorable will admire Whipple’s skill in drawing out vivid line after vivid line from his diplomatic and reticent subjects. And although the chiefs he interviewed have beliefs across all the social and political spectrum, they all agree about the job itself. “If people tell you they want to leave the White House, they’re probably lying,” George W Bush’s chief of staff Andrew Card tells Whipple. “Nobody really wants to leave the White House.”

On the morning of September 11, 2001, Card had to whisper in the president’s ear, “America is under attack.” And it was Card who was there in the room during the tense, calamitous days of Bush’s decisions to launch the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan, decisions about which he is fascinatingly blunt.

“I did not see it necessarily as Vietnam but I could see that the climate in America would be more akin to the climate around Vietnam,” Card tells Whipple. “I remember being concerned about how long the war was taking, both in Afghanistan and Iraq. And I knew that America could become war-weary very quickly.”

Card’s experiences in the job featured momentous wars and natural disasters. Not every chief Whipple interviews has such high-stakes war stories to relate. But the personal drama in every administration is no less intense, and these chapters capture that drama in ways a more distanced, scholarly approach would not be likely to match.

There are make-or-break issues in every one of the administrations The Gatekeepers covers, from the Nixon years in which chief of staff H R "Bob" Haldeman set the pattern for the modern iteration of White House chief of staff, according to Whipple, through to the chiefs employed by presidents Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George H W Bush, Bill Clinton, George W Bush and Barack Obama.

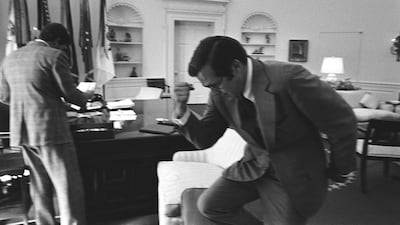

Ford, for instance, came to the job from his Congressional office in which he had favoured an informal approach among his top staff, a “spokes of the wheel” model that allowed fairly open access to the boss. And for a while, he duplicated this pattern in the Oval Office, favouring his official photographer David Hume Kennerly on personal grounds – until Donald Rumsfeld, Ford’s first choice for chief of staff, who became secretary of defence under George W Bush, objected to the chaos created by the “spokes of the wheel” approach at the presidential level.

Ford reluctantly agreed: “Without a strong decision-maker who could help me set my priorities,” he recalled, “I’d be hounded to death by gnats and fleas. I wouldn’t have time to reflect on basic strategy or the fundamental direction of my presidency.”

The nuance of Ford’s observation – the way the chief of staff simultaneously alleviates and accentuates the essential loneliness of the presidency – is realised in half-a-dozen variations throughout Whipple’s book. Some presidents, like Reagan, favoured a chief who would function almost as a co-chairman, running meetings and keeping a tight rein on the executive branch; Reagan got “consummate Washington insider” James Baker to perform just such a function – something the previous president, Jimmy Carter, had failed to do. Whipple points out: “Carter was arguably the most intelligent president of the twentieth century, whereas Reagan had once been called, unfairly, ‘an amiable dunce’. Yet in choosing Baker, Reagan had intuited something his predecessor did not grasp.”

Other presidents preferred a less dominant individual, a discussion-facilitator more on the lines of president Obama’s fourth, and final, chief, former deputy national security adviser Denis McDonough, who was reluctant to make policy arguments alone with the president. “It’s not fair,” he tells Whipple. “I make it when somebody can rebut it – keep me honest. Hold me accountable.”

But despite the general note of self-effacement struck by all the interview subjects in these pages, few of them actually displayed that kind of self-effacement in the job – the pervasive impression is that a strong, perhaps even unpleasant, personality is virtually a requirement.

Foremost in that category in modern times would be former Republican governor of New Hampshire John Sununu, who cut a bloody swath as president George H W Bush’s ringleader. “Sununu was better at managing the boss than the staff,” writes Whipple, adding diplomatically, “The president appreciated his intelligence and wit.”

Sununu's reign as chief of staff, before it ended in a minor scandal, was legendary for its ruthlessness, but owing to its dependency on friendly interviews, The Gatekeepers contains very little of that kind of raw narrative.

President Clinton’s second chief, Leon Panetta, provides some of the book’s saltiest quotes, but the prevailing impression is one of judicious friendliness. Obama’s first chief, Rahm Emanuel, can talk about doing “the Wrap” with the President, a walk around the circular driveway of the White House’s South Lawn, but instead of learning about the political plotting in those conversations, we hear that First Lady Michelle Obama would sometimes tease, “Oh, look – the boys are on their walk!”

Given the political climate in the US, Whipple can hardly avoid casting nervous glances at the current Oval Office. “Donald Trump’s stunning election victory over Hillary Clinton poses an unsettling question: What kind of president will he be?” he asks. “Will he run the White House the way he campaigned: demonizing opponents and making seat-of-the-pants decisions, with no regard for facts or nuance? Or will the burdens of the office put a brake on Trump’s worst instincts – and enable him to govern effectively?”

These questions were set down on paper long before the breaking news of the day, of course. In the few weeks since The Gatekeepers appeared in bookstores, some tentative answers have started to surface, and in the face of deranged late-night tweets, gratuitous personal insults delivered to key international allies, and major legislative defeats suffered at the hands of his own political party, not even Trump's staunchest supporters would say those answers point toward "govern effectively". No, even this early, one thing is crystal clear: Priebus shouldn't get too comfortable in his office.

Steve Donoghue is managing editor of Open Letters Monthly.