About a year ago, art collector and lecturer Sultan Al Qassemi, who runs the Barjeel Art Foundation in Sharjah, pledged to make his collection of modern and contemporary Arab art representative of both male and female artists.

He acquired a greater number of works by women artists, and then applied these changes to the display of the collection, which is on long-term loan to the Sharjah Art Museum. Titled A Century in Flux: Highlights from the Barjeel Art Foundation: Chapter II, the show now finishes its first year of gender parity – but the decision remains controversial. What happens when, instead of working towards an equal representation of men and women through incremental change, you leapfrog to its realisation?

The change to the exhibition itself is – to a degree I did not expect – palpable. More women are depicted, particularly in active roles within domestic life: looking after children, tending to pets, organising families. These portrayals are often heroic rather than cloying, such as Inji Efflatoun's stirring portrait from the 1950s, of a woman breastfeeding, her spine ramrod straight, her face aloft (Motherhood). Efflatoun was imprisoned for four years in 1959 for her activism.

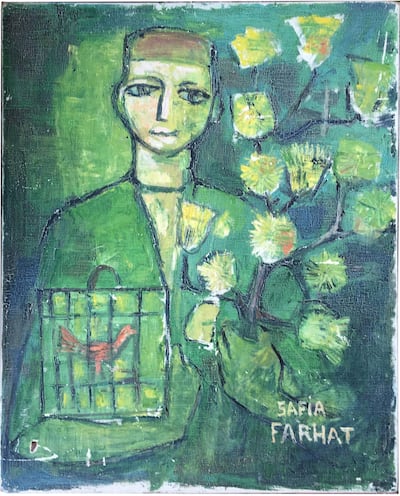

Conflict and misfortune, major themes of the first exhibition, are refracted via images of care. The Hunger (1963), made by Lebanese-Syrian artist Derrieh Fakhoury in response to the 1961 Syrian drought, shows a mother holding a starving child. The skin of both are a sallow green; hers is a bit more sickly. And there are images of care in a less iconic sense, such as a woman cheerily feeding a peacock in Algerian artist Baya's Woman with Two Peacocks and Aquarium (1968), and in Tunisian artist Safia Farhat's Child with Heliotropes (1963), in which a young boy proudly shows off his pet bird.

“Women depict women,” says Al Qassemi. “One reason why you should show women, is that they know women. They depict scenes they have access to. [Saudi artist] Safeya Binzagr had access to women’s weddings and the henna ceremony. Men weren’t allowed in. How can you expect men to go in and paint the henna ceremony?”

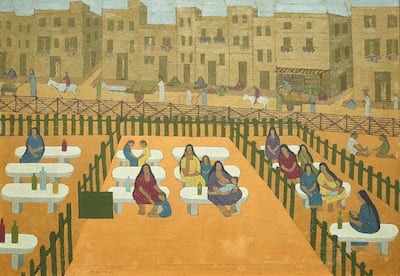

This access seems to have changed the works in subtle ways. Take the case of two works showing doctor's offices: Mariam Abdel-Aleem's Clinic and Menhat Helmy's Outpatient Clinic (both 1958). They depict the large-scale investment in Egypt's public-health infrastructure in the 1950s, after the country's new constitution of 1952 pronounced free medical care as a right for all.

In Abdel-Aleem’s portrayal, four women wait with their children in a line. A child hangs off the neck of one weary-looking mother; another carries a bowl and vegetables, perhaps as a snack to keep her children occupied. Abdel-Aleem’s painting abuts Helmy’s, in which the latter’s more stylised, folkloric figures sit on benches outdoors. Some hold children on their knees; others nurse while they all wait.

As I look back and forth between them, I feel myself trading my art critic's hat for my weekend one. Taking children to the doctor is a unique mix of boredom and anxiety, the two criss-crossing emotions of early motherhood: the waits are long, there is the worry that something might be discovered to be wrong, as well as the low-level stress of persuading children to be on their best behaviour in front of an authority figure who, the last time, poked them full of needles. Or, worse, the fear of judgment, where the forgotten start date for a rash could turn into a verdict on you, the suddenly unworthy mother. The apparently neutral space of the waiting room is rendered in all its emotional complexity.

But is the prevalence of these heroic and sensitive depictions art historically accurate? They might serve as an immense validation, but are they really the hidden half of Arab art history? It turns out that the decision to hang the works as 50/50 men and women has not been a straightforward one, and it has divided opinion even among those who worked on the show.

For Palestinian art historian and NYU Abu Dhabi professor Salwa Mikdadi, who curated the first chapter of A Century in Flux, in 2018, and assisted on this one, the move towards gender parity involves a revision of history. "While the exhibition is beautifully mounted, it does not reflect the reality, which is more complex than equal representation," she says.

Sticking to an equal split means overstating the contribution of women artists at points in the historical narrative where they were simply not so present, and glosses over the details of how they were held back. “When I look at the history of women in art in the context of the region, I don’t see women as intentionally marginalised,” Mikdadi says.

In much of the 20th century, women were discouraged from professions such as law, civil engineering and medicine, and art was actually seen as an appropriate field for them. Their ability to contribute was suppressed, though, by social pressures against mixing with men, which kept them out of art academies and the male-dominated bastions of art societies and groups. Their subsequent lack of university degrees meant they were not selected for exhibitions and did not receive the respect their work deserved, explains Mikdadi.

Still, she says, from the 1920s, several women received government scholarships and studied in Europe and England, and local art academies were co-educational. By the 1950s, women artists were contributing to art education in the Arab world. Other female artists rose to lead art institutions, such as Wijdan Ali, who set up the Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts, and the late Layla Al Attar, who directed the Iraqi National Art Museum.

Mikdadi has actively promoted women artists, curating the first major exhibition of female Arab artists, Forces of Change, in 1994, for the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC.

Showing women who were not known at the time, Mikdadi argues, risks marginalising the women who challenged the restrictions. Al Qassemi welcomes Mikdadi's dissenting opinion – but remains unperturbed by the contention that Barjeel's display is misrepresentative. "Who says I'm interested in the official narrative?" he says.

“The narrative is that women were not shown, minority artists were not shown, underprivileged individuals were not shown, people who had no connections were not shown. If we were all to stick with displaying exhibitions that adhere to the official narrative, there will be no progress, no expansion of what art is.”

Al Qassemi is in a privileged position to make the decision. Unlike a public national museum, which would have stronger constraints in terms of curatorial experiments, the arrangement between the privately run Barjeel Art Foundation and the Sharjah Art Museum allows for more risk-taking, including this kind of retroactive affirmative action. He says he is also seeking to show more work by religious and ethnic minorities, with paintings by Jewish, Baha'i and Amazigh artists, and he hopes other institutions will follow his lead.

“Do you really need to see more Picassos? You already are inundated with Picassos, so maybe three or four works will suffice, and then you start expanding what art is and showing other artists,” he says. “How much more enriched is the MoMA display with its Saloua Raouda Choucair [painting] on show. How much more enriched is humanity? Just think about it, the fact that you have young Americans seeing works by a Lebanese artist who was obscure a few years ago – unknown to them. The experience of going to the museum is so much more enriching, and nothing was taken away from it.”

Barjeel's decision has already brought new artists into the spotlight, particularly female Iraqi and Egyptian artists of the 1960s and 1970s, a period the collection is strong on. While filling out gaps in the art historical narrative is also a traditional role of scholarship, the artists here have been fast-tracked from research to museum exhibition: which means not only validation, but a larger chance for them to be seen by the public. And greater exposure means more scholarship, ultimately allowing the nuances of women's contribution (and its lack thereof) to be better discussed.

For now, Chapter II has opened the debate – and put the results of its proposition out there for all to consider or simply enjoy.

A Century in Flux: Highlights from the Barjeel Art Foundation: Chapter II is at the Sharjah Art Museum until March