"If people who can't dance have two left feet, when it comes to drawing, I have two left hands."

Manal Hamid's introduction may be self-effacing but as an icebreaker, her comment is spot on. A ripple of laughter spreads around the gilded meeting room at Abu Dhabi's Eastern Mangroves Hotel & Spa by Anantara, and the 18-strong group - which includes professional artists, designers, teachers, students, and full-time mums - relaxes as introductions proceed.

They have gathered for the Journey into Islamic Pattern Design, a five-day introductory course in Islamic geometrical design, and the pads, pencils, scale rules and compasses stacked neatly at each seat act as a clear and slightly daunting indicator of what is to come.

Adam Williamson, an award-winning sculptor, and Richard Henry, an artist, teacher and geometer, are delivering the course. Both are alumni of the Prince's School of Traditional Arts in London, an international centre of excellence in the practice of traditional Islamic arts. Both are also former students of the architect and thinker Keith Critchlow, one of the world's foremost experts in sacred geometry. The pair met eight years ago while teaching on the British Museum's World Arts and Artefacts programme in London and now run their own school, The Art of Islamic Pattern, from Williamson's studio in East London.

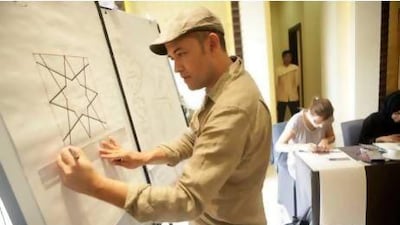

Dressed in a flat cap and waistcoat, Henry is eloquent, meticulous and precise - everything you would expect from a man who has made philosophy, mathematics and geometry his life's work. Softly spoken, diffident almost, Williamson specialises in carving, sculpture and illumination that use Islimi, the rhythmic, scrolling and interlacing patterns more commonly known as "Arabesque".

The list of their teaching positions, clients and commissions attests to their knowledge, experience and skill. These include the British Library, the Victoria and Albert Museum, Shakespeare's Globe, Prince Charles, Westminster Abbey and the Universities of both Oxford and Cambridge.

Williamson shares his calling as an artist and a craftsman with his family. "My father is a carpenter, my mother is a poet and a printmaker, but they were both very interested in Sufism so I've always been surrounded by arts from the East. I grew up in a Muslim environment."

Henry leads the teaching, starting with a brief lecture on the relationship between geometry, philosophy and the natural patterns that repeat in everything from the microscopic structure of muscle tissue to the structure of Islamic architecture and the solar system. For Henry, geometry - from the Greek "earth measure" - is something found in the world that enables us to relate to it. He quotes an epistle from a 10th century encyclopaedia, written by the mysterious Brethren of Purity, a secret society of Muslim philosophers from Basra, which describes geometry as "one of the gates through which we move to the knowledge of the evidence of the soul, and that is the root of knowledge".

For the students gathered at the hotel, that journey begins with a single vertical line, drawn by Henry on a flip chart in front of the class. The students follow his every move, creating 18 replicas of his master drawing on the pads in front of them, and as they do so, the room soon settles to the soft sound of pencils arching across paper. Troublesome hair is soon tied back, and many of the students - who started the session in a sitting position - now arch over tables, desperate to get their pattern-making right. Within minutes, a rose-shaped diagram appears, a circle for each day of creation and another that signifies the eventual day of rest.

Henry then starts to draw lines of radial symmetry, more circles, and long, interrupted lines that bisect the page. Stars and then hexagons begin to emerge from the tutor's diagram at the same moment confused giggles emerge from the group. "Sorry Richard," says one student, "but speed is not our forte. Would you mind doing that again?"

"This is a complex drawing to start with," Henry replies. "Please don't be disheartened."

Luckily, the group is undeterred and by the end of the five-day course, they have progressed to geometries that are more complex. Remarkably, the final session is a practical session in illumination and gilding. Manal Hamid, who started the week with "two left hands", is delighted with the results.

If the calibre of the tutors wasn’t enough to dispel the notion that The Art of Islamic Pattern is little more than a diversion devised for ‘ladies who lunch’, the level of commitment displayed by some of the students is. Charlotte Baldini’s father may live and work in Abu Dhabi, but the 23-year-old art student has travelled from Italy for the week just to take the course. Rather than commute from Sharjah each day, May Rashed has come to stay with her sister in Abu Dhabi. She abandoned a career in quality management in 2011 to pursue her passion for art.

"I have an MA in quality management and I had a good job as a quality manager, but I went to the Venice Biennale in 2011 for one month and that made me see clearly what I want to do. Art is my passion and I have to follow it."

A professional interior designer, Jessica Daw moved to Abu Dhabi from London at the end of 2012. She sees the course as an opportunity not only to engage with the culture of her adopted home, but to interact with its people as well. "I want to absorb something of this place, of being in the Middle East, into the work that I do. It's a chance to meet Emirati ladies, which is an opportunity you don't often have, so it's also interesting from a social perspective."

When judged from this perspective, the course is a success. Seventy per cent of the students are Emiratis, while expats including Lebanese, English, Polish and Indian fill the remaining places in the two classes held each day. By the end of the course, the effort made by the students has helped them to experience a shared sense of achievement. The potential for this kind of interaction inspired Dr Zeinab Saleh Farah to organise the course under the auspices of her fledgling cultural organisation, Bayt Al Qindeel.

"The philosophy behind Bayt Al Qindeel is to create dialogue. Bayt Al Qindeel in Arabic means 'House of Light'. Qindeel means 'lantern'. I want it to be a forum of for cultural exchange. It's just a very tiny contribution, but I want us to exchange ideas and to see how similar we are."

Farah's family have lived in Abu Dhabi since 1967 when her father, Saleh Farah, arrived as Sheikh Zayed's legal adviser, and as Chief Justice helped to establish the emirate's judiciary. A respected scientist, Farah became a consultant paramedical virologist at the Al Jazeera hospital in Abu Dhabi, where she worked for 22 years. She then experienced a design course for herself in 2011 while she was studying for her second MA at the London School of Economics. "At the beginning, I introduced myself and I explained that I was a scientist, but that I wanted the other side of my brain to work as well. I've never drawn or done anything since school but I was pleasantly surprised."

The sentiment is echoed by May Rashed, for whom the course in Abu Dhabi is something that has exercised both the intellect and the soul. "This has been an exercise for my eyes," she explains. "It has been a good exercise for me as an artist, but this is not only about creating patterns. There is a spiritual side to the geometry that connects our faith to art. Art and Islam can be a sensitive topic, but doing such courses can enhance our faith and allow us to relate to it even more."

Course tutor Henry likes to think of geometrical design as a form of "visual yoga" with an appeal that extends beyond an individual's culture or ethnicity.

"I think experiencing that meditative aspect is one of the most important things somebody could take from this class. It's about engaging with the process. You start with this circle, a perfect form, and you see how that unfolds. There's a beauty … and a wonderful harmony in that."

Beauty there may be, but for some students the therapy also comes at a price, as Manal Hamid says. "Sometimes, I've gone away with a headache. When people see these patterns, they have no idea how much time, concentration, effort and energy goes into producing them." For Darcy Vasickowa, a full-time mother who hopes to establish her own fabric business, even moments of frustration brought some reward. "It's very easy to lose sight of the bigger picture … but it's been nice to get lost in it. It was therapeutic."

Henry believes that much of that sense of engagement stems from the fact that the physical act of creation is a process that many of us no longer have in our daily lives. "Just doing things by hand is a very powerful thing," he explains, "because it's something that we're losing in a world where we are used to doing everything by computer."

Ironically, modern technology enabled Farah to make the Abu Dhabi course a success, as a direct approach through social media enabled her to reach out to individuals she would otherwise have missed.

"I have my daughters to thank for that. When my daughters found me getting in a twist they said, 'Let's put it online', so that's what we did. They set up a Facebook page and linked that to Twitter and Instagram accounts. That allowed me to reach out to a different audience."

Farah hopes that the audience will grow sufficiently to enable more courses to run in the autumn and for Bayt Al Qindeel to expand.

"I hope to be able to bring other initiatives to Abu Dhabi that may not pertain directly to art but that will also foster cultural dialogue. They might be more workshops or speakers but whatever it is the idea is to foster interaction and to explore our common humanity."

She remains however, a realist and admits that the key to future success lies in attracting funding to allow students "who don't have big names or big money" to participate in Abu Dhabi's burgeoning creative culture. Etihad Airways sponsored 10 students for the inaugural courses, but Farah hopes for increased sponsorship from a wider range of local organisations in future.

"I have lived to witness Abu Dhabi become a cultural hub and a melting pot. What I'm trying to do with Bayt Al Qindeel is to work with that wave. We just need something to create the right spark."

The facts

The five-day Journey into Islamic Pattern Design workshop organised by Bayt Al Qindeel cost Dh2,000 including refreshments and art materials. The course is part of the ongoing Anantara Art Series, a recent initiative showcasing local art in the hotels dedicated exhibition space (www.anantara.com). For more information about Bayt Al Qindeel, visit its page on Facebook

Adam Williamson and Richard Henry run workshops on Islamic geometry for adults and children from their base in London, as well as organising field trips to study Islamic art in situ. The next trip, to Fez in Morocco, is planned for September 18-21. For more information, visit www.artofislamicpattern.com

Follow us

Follow us on Facebook for discussions, entertainment, reviews, wellness and news.