Just how much artistic talent is there in the UAE? When the the Salama bint Hamdan Emerging Artists Fellowship (SEAF) was launched to support emerging Emirates-based artists in 2013, there was talk that its organisers, the Salama bint Hamdan Al Nahyan Foundation and the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), would struggle to find sufficient talent to run the invitation-only course on an annual basis.

Four years and more than 50 alumni later – four of whom have gone on to receive Master of Fine Arts (MFA) degrees and 15 of whom are currently studying – work by the latest batch of SEAF fellows is now on display in Community & Critique: SEAF 2016/17 Cohort 4, which opened on Saturday at Warehouse421 in Mina Zayed.

Ostensibly, the title of the show refers to the conditions that this latest crop of fellows have been working in since November – all 15 have shared studio space in a villa on Abu Dhabi's Breakwater – and to the sense of creative and critical community the experience has forged.

But what's clear from the exhibition is that the fellows' sense of community extends far beyond the programme, looking outwards as well as inwards, and that in a surprising number of cases it includes a critique of society as penetrating as it is unexpected.

The work of 23-year-old Emirati artist Sara Alahbabi is a case in point.

Displayed in a darkened room, the untitled work consists of a series of mirrors, each bearing a phrase in Arabic calligraphy that is used in everyday life as a form of criticism to control the behaviour and self-image of young women.

"She must be perfect, intelligent and cautious. She must not aspire to be human; she must not utter words that can challenge nonsense; and she must not do what can compromise her carefully-fashioned image," Alahbabi writes in the statement that accompanies her work.

"For the sake of her freedom, she must no longer be human, and for the sake of her sanity, she must find ways to manoeuvre around her expectations."

"Ayab" is written on one of the mirrors, which Alahbabi defines as a word more censorious than "haram", and which can be applied to any form of behaviour society finds unacceptable, but which tellingly also combines the notion of something that is flawed.

A second displays the Arabic word for criticised – "Manqood" – while others contain phrases such as "Don't let anyone find you at fault" and "Every woman is a white page", a saying that not only emphasises the idea of female purity and how easily it can be besmirched, but also the notion that a woman is a passive tabula rasa, waiting to be written on.

By inviting her audience, especially Arabic speakers, to stand in front of each mirror, Alahbabi hopes they will reflect on the power of words, the pressures facing women and the expectations they have to navigate on a daily basis.

"I choose to make these comments using art because I feel like it's a much more powerful mechanism, but also because when people come to an art exhibition they understand that it might be a little controversial," the New York University Abu Dhabi graduate tells me.

"I've only just scratched the surface with this work, but what's important for me is to have established a platform for the discussion of these issues in society."

Alahbabi's work is well placed within the show, engaging as it does with the thematically connected but very different work by her neighbour, Maitha Abdalla, a 28-year-old artist originally from Sharjah.

As well as a large wall painting and video installation, Sinner's Dance (2017) features a menagerie of animal statues that include hens and pink rabbits as well as fantastical creatures that are part-bird and part-human, and part-man, part-wolf.

Inspired by theatre, children's tales and time spent teaching art and English in a Turkish orphanage, Abdalla's delightfully surreal and carnivalesque figures depict individuals who have been rendered grotesque and deformed because of actions deemed sinful by their peers, and who are now seeking forgiveness.

"I always knew that my work was influenced by theatre, but the fellowship gave me the freedom and pushed me to work with different media in the studio," the Zayed University graduate and recipient of the Sheikha Manal Young Artist Award tells me about her work, which represents a departure from her usual focus on painting.

Like many of her fellows, the process of taking part in the SEAF has allowed Abdalla to arrive at a point where she is more certain about her future plans. "Originally, I always wanted to write stories but even though I was good at imagining them, I wasn't very good at it," says the artist, who originally studied English at Middlesex University in the UK. "But now I am an artist and I know now where my work is heading. The programme has taken me to a place where I am very confident about what I want to do next and I know the steps I have to take.

"I definitely want to study for an MFA," she says.

That same determination to make art can be felt throughout the exhibition and, as with previous editions of the SEAF, the current cohort of fellows includes people who have used the programme to re-evaluate their careers and to embark on different paths.

One of these artists is Areeb Masood, a jewellery and accessories designer who was born and raised in Dubai, and who is also a qualified teacher.

"I love working with my hands but I applied to SEAF because I thought it was time for a change, and the programme felt like the perfect place for me to explore and for me to develop as an artist," says Masood, 28.

For Community & Critique, Masood has moved beyond her usual practise of jewellery design to create a series of suspended acrylic tiles that join together, in chains, to form the ceiling of a narrow, passage-like chamber that challenges visitors to interact with it and enter inside.

______________

Read more:

UAE artists transport the Emirates to Berlin

Stills curated from the Arab Image Foundation’s archive reveal a bittersweet narrative

Art exhibitions in the UAE: what to see now the new season is here

______________

"For me, jewellery is sculpture for the body, and what somebody wears tells you a lot about them, but so does their environment," Masood says.

She explains that her installation aims to change your perspective while making you feel that you are inhabiting two places at once.

For Masood, one of the key attractions of SEAF was the way – thanks to its connections with RISD – that it combines experimental studio-based practise with critical inquiry, something she believes is unique in the UAE, and now that she is a SEAF alumna, it's in that direction that she wants to proceed.

"Given where we are, there are certain things that you have to be subtle about, and that will take a lot more investigation and thought and discussion, but ultimately, I'd like to combine that with making things," she explains.

"I'd like to pursue an MFA now and that may involve going abroad, but the aim is always to come back here. For me that's important because my family are here and this is home."

As usual with the SEAF cohort, this year's fellows reflect the wider demographic make-up of the UAE.

As well as Emirati artists it includes creatives such as Masood who were born in the country and have known no other home, as well as foreign nationals born elsewhere but who are long-term residents, such as the Palestinian designer, Dina Khorchid, who was born in Kuwait.

No stranger to the Salama bint Hamdan Al Nahyan Foundation, Khorchid has been the organisation's chief designer for the last four years but she admits that she was surprised to be nominated for a place in the fellowship – the only way a candidate can be considered for the scheme. "I only knew I had been nominated because of the email I received telling me that I had been; it was a pleasant surprise," she admits.

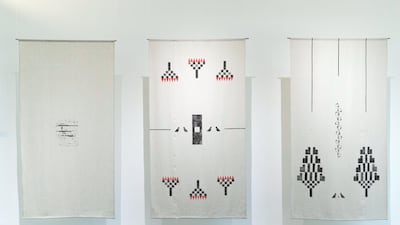

A graphic designer who has also exhibited throughout the UAE, Khorchid's work also featured as part of a group show at the UK's Liverpool Arabic Arts Festival in 2014. She has taken the opportunity offered by the fellowship to explore an interest in textiles and this is the basis of her installation at Warehouse421.

Combining linen and woodblock printing, the profoundly-personal work explores Khorchid's family history, half-remembered memories and the loss of her father. The work's title, Engram, refers to a hypothetical trace that a memory can leave on the brain.

As well as memories, Khorchid's work also refers to the symbolism of birds and trees from her Palestinian heritage.

"The fellowship has allowed me to bridge a gap between design and art in my own practise," she says, explaining that she feels inspired by the prospect of exploring textiles further. "I'd love to be in a community similar to SEAF where you can draw off other people and be in a messy studio environment. That's really needed here."

The work in Community & Critique may have been made by younger artists at the start of their careers, but by engaging intelligently and eloquently with issues that society still finds it difficult to engage with, such as social taboos, gender roles, religion and the experience of long-term residents and migrants, the SEAF show illustrates just what art is capable of and why it is important.

At its best, the work of the SEAF fellows is critically-engaged, aesthetically adventurous and intellectually fearless. Youthful it may be, but immature it most certainly is not.

Community & Critique: SEAF 2016/2017 Cohort 4 will run at Warehouse421, Mina Zayed, Abu Dhabi, until January 14. For more information visit www.warehouse421.ae